تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

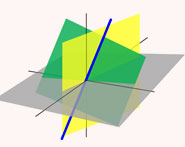

الهندسة

الهندسة

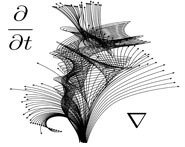

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 15-1-2016

Date: 13-1-2016

Date: 12-1-2016

|

Born: January 1526 in Bologna, Papal States (now Italy)

Died: 1572 in (probably) Rome, Papal States (now Italy)

Rafael Bombelli's father was Antonio Mazzoli but he changed his name from Mazzoli to Bombelli. It is perhaps worth giving a little family background. The Bentivoglio family ruled over Bologna from 1443. Sante Bentivoglio was "signore" (meaning lord) of Bologna from 1443 and he was succeeded by Giovanni II Bentivoglio who improved the city of Bologna, in particular developing its waterways. The Mazzoli family were supporters of the Bentivoglio family but their fortunes changed when Pope Julius II took control of Bologna in 1506, driving the Bentivoglio family into exile. An attempt to regain control in 1508 was defeated and Antonio Mazzoli's grandfather, like several other supporters of the failed Bentivoglio coup, were executed. The Mazzoli family suffered for many years by having their property confiscated, but the property was returned to Antonio Mazzoli, Rafael Bombelli's father.

Antonio Mazzoli was able to return to live in Bologna. There he carried on his trade as a wool merchant and married Diamante Scudieri, a tailor's daughter. Rafael Bombelli was their eldest son, and he was one of a family of six children. Rafael received no university education. He was taught by an engineer- architect Pier Francesco Clementi so it is perhaps not too surprising that Bombelli himself should turn to that occupation. Bombelli found himself a patron in Alessandro Rufini who was a Roman noble, later to become the Bishop of Melfi.

It is unclear exactly how Bombelli learnt of the leading mathematical works of the day, but of course he lived in the right part of Italy to be involved in the major events surrounding the solution of cubic and quartic equations. Scipione del Ferro, the first to solve the cubic equation was the professor at Bologna, Bombelli's home town, but del Ferro died the year that Bombelli was born. The contest between Fior and Tartaglia (see Tartaglia's biography) took place in 1535 when Bombelli was nine years old, and Cardan's major work on the topic Ars Magna was published in 1545. Clearly Bombelli had studied Cardan's work and he also followed closely the very public arguments between Cardan, Ferrari and Tartaglia which culminated in the contest between Ferrari and Tartaglia in Milan in 1548 (see Ferrari's biography for details).

From about 1548 Pier Francesco Clementi, Bombelli's teacher, worked for the Apostolic Camera, a specialised department of the papacy in Rome set up to deal with legal and financial matters. The Apostolic Camera employed Clementi to reclaim marshes near Foligno on the Topino River, southeast of Perugia in central Italy. This region had became part of the Papal States in 1439. It is probable that Bombelli assisted his teacher Clementi with this project, but we have no direct evidence that this was the case. We certainly know that around 1549 Bombelli became interested in another reclamation project in a neighbouring region.

It was in 1549 that Alessandro Rufini, Bombelli's patron, acquired the rights to reclaim that part of the marshes of the Val di Chiana which belonged to the Papal States. The Val di Chiana is a fairly central region in the Tuscan Apennines which was not well drained either by the Arno river which runs north westgoing through Florence and Pisa to the sea, or by the Tiber which runs south through Rome. By 1551 Bombelli was in the Val di Chiana recording the boundaries to the land that was to be reclaimed. He worked on this project until 1555 when there was an interruption to the reclamation work.

While Bombelli was waiting for the Val di Chiana project to recommence, he decided to write an algebra book. He had felt that the reason for the many arguments between leading mathematicians was the lack of a careful exposition of the subject. Only Cardan had, in Bombelli's opinion, explored the topic in depth and his great masterpiece was not accessible to people without a thorough grasp of mathematics. Bombelli felt that a self-contained text which could be read by those without a high level of mathematical training would be beneficial. He wrote in the preface of his book [2] (see also [3]):-

I began by reviewing the majority of those authors who have written on [algebra] up to the present, in order to be able to serve instead of them on the matter, since there are a great many of them.

By 1557, the work at Val di Chiana still being suspended, Bombelli had begun writing his algebra text. We will study in detail the contents of the work below. Suffice to say for the moment that, in 1560 when work at Val di Chiana recommenced, Bombelli had not completed his algebra book.

Work at the Val di Chiana marshes could not have been far from completion when it had been suspended, for it was completed before the end of 1560. The scheme was a great success and through the project Bombelli gained a high reputation as an hydraulic engineer. In 1561 Bombelli went to Rome but failed in an attempt to repair the Santa Maria bridge over the Tiber. However, with reputation still high, Bombelli was taken on as a consultant for a project to drain the Pontine Marshes. These marshes in the Lazio region of south-central Italy had been an area where malaria had been a health hazard since the period of the Roman Republic. Several emperors and popes made unsuccessful attempts to reclaim the area but all, including the one which Bombelli acted as consultant on for Pope Pius IV, came to nothing. [It was not until 1928 that the Pontine Marshes were finally drained.]

On one of Bombelli's visits to Rome he made an exciting mathematical discovery. Antonio Maria Pazzi, who taught mathematics at the University of Rome, showed Bombelli a manuscript of Diophantus's Arithmetica and, after Bombelli had examined it, the two men decided to make a translation. Bombelli wrote in [2] (see also [3]):-

... [we], in order to enrich the world with a work so finely made, decided to translate it and we have translated five of the books (there being seven in all); the remainder we were not able to finish because of pressure of work on one or other.

Despite never completing the task, Bombelli began to revise his algebra text in the light of what he had discovered in Diophantus. In particular, 143 of the 272 problems which Bombelli gives in Book III are taken from Diophantus. Bombelli does not identify which problems are his own and which are due to Diophantus, but he does give full credit to Diophantus acknowledging that he has borrowed many of the problems given in his text from the Arithmetica.

Bombelli's Algebra was intended to be in five books. The first three were published in 1572 and at the end of the third book he wrote that [1]:-

... the geometrical part, Books IV and V, is not yet ready for the publisher, but its publication will follow shortly.

Unfortunately Bombelli was never able to complete these last two volumes for he died shortly after the publication of the first three volumes. In 1923, however, Bombelli's manuscript was discovered in a library in Bologna by Bortolotti. As well as a manuscript version of the three published books, there was the unfinished manuscript of the other two books. Bortolotti published the incomplete geometrical part of Bombelli's work in 1929. Some results from Bombelli's incomplete Book IV are also described in [17] where author remarks that Bombelli's methods are related to the geometrical procedures of Omar Khayyam.

Bombelli's Algebra gives a thorough account of the algebra then known and includes Bombelli's important contribution to complex numbers. Before looking at his remarkable contribution to complex numbers we should remark that Bombelli first wrote down how to calculate with negative numbers. He wrote (see [2] or [3]):-

Plus times plus makes plus

Minus times minus makes plus

Plus times minus makes minus

Minus times plus makes minus

Plus 8 times plus 8 makes plus 64

Minus 5 times minus 6 makes plus 30

Minus 4 times plus 5 makes minus 20

Plus 5 times minus 4 makes minus 20

As Crossley notes in [3]:-

Bombelli is explicitly working with signed numbers. He has no reservations about doing this, even though in the problems he subsequently treats he neglects possible negative solutions.

In Bombelli's Algebra there is even a geometric proof that minus time minus makes plus; something which causes many people difficulty even today despite our mathematical sophistication.

Bombelli, himself, did not find working with complex numbers easy at first, writing in [2] (see also [3]):-

And although to many this will appear an extravagant thing, because even I held this opinion some time ago, since it appeared to me more sophistic than true, nevertheless I searched hard and found the demonstration, which will be noted below. ... But let the reader apply all his strength of mind, for[otherwise] even he will find himself deceived.

Bombelli was the first person to write down the rules for addition, subtraction and multiplication of complex numbers. He writes "√-n as "plus of minus", -√-n as "minus of minus", and gives rules such as (see [2] or [3]):-

Plus of minus times plus of minus makes minus ["√-n . +√-n = -n]

Plus of minus times minus of minus makes plus ["√-n . -√-n = +n]

Minus of minus times plus of minus makes plus [-√-n . +√-n = +n]

Minus of minus times minus of minus makes minus [-√-n . -√-n = -n]

After giving this description of multiplication of complex numbers, Bombelli went on to give rules for adding and subtracting them.

He then showed that, using his calculus of complex numbers, correct real solutions could be obtained from the Cardan-Tartaglia formula for the solution to a cubic even when the formula gave an expression involving the square roots of negative numbers.

Finally we should make some comments on Bombelli's notation. Although authors such as Pacioli had made limited use of notation, others such as Cardan had used no symbols at all. Bombelli, however, used quite sophisticated notation. It is worth remarking that the printed version of his book uses a slightly different notation from his manuscript, and this is not really surprising for there were problems printing mathematical notation which to some extent limited the type of notation which could be used in print.

Here are some examples of Bombelli's notation.

Despite the delay in publication, Bombelli's Algebra was a very influential work and led to Leibniz praising Bombelli saying he was an:-

... outstanding master of the analytical art.

Jayawardene writes in [1] that in his treatment of complex numbers Bombelli:-

... showed himself to be far ahead of his time, for his treatment was almost that followed today.

Crossley writes in [3]:-

Thus we have an engineer, Bombelli, making practical use of complex numbers perhaps because they gave him useful results, while Cardan found the square roots of negative numbers useless. Bombelli is the first to give a treatment of any complex numbers... It is remarkable how thorough he is in his presentation of the laws of calculation of complex numbers...

It seems to be quite fair to describe Bombelli as the inventor of complex numbers. Nobody before him had given rules for working with such numbers, nor had they suggested that working with such numbers might prove useful. Dieudonné does not appear to agree with this assessment, however, for in his review of [5] and [6], he writes:-

... imaginaries had been used long before Bombelli's book, and it is therefore not quite justified to call him the "first discoverer" of complex numbers.

I [EFR] feel that Dieudonné is wrong here as I believe he is when he writes that Bombelli's Algebra

... did not sell very well, nor apparently did it have much influence on later developments.

I think that Bombelli's Algebra is one of the most remarkable achievements of 16th century mathematics, and he must be credited with understanding the importance of complex numbers at a time when clearly nobody else did.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ووفد من جامعة البصرة يبحثان سبل تعزيز التعاون المشترك

|

|

|