تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

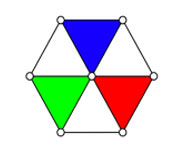

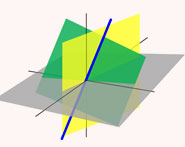

الهندسة

الهندسة

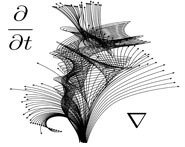

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 31-5-2017

Date: 18-5-2017

Date: 22-5-2017

|

Died: 20 January 1971 in Epe, The Netherlands

Jan A Schouten's mother was Hulda Ludowica Elwira Deetz who was the daughter of Friedrich Deetz, the director of the hospital in Wezel, and Emilie Friederike Klonne. Hulda, born in Wezel on 9 February 1847, married Jan Schouten in 1882. Jan, born in Dordrecht on 14 September 1845, was from a leading family of shipbuilders but had trained as a lawyer and was an advocate and attorney. Jan and Hulda lived first in Overtoom but moved to Nieuwer Amstel (now part of Amsterdam) where their son, Jan Arnoldus, the subject of this biography, was born. The family moved again in 1886, this time moving to Nijmegen where Jan Arnoldus was brought up. We note at this point that Jan Schouten died in Nijmegen on 10 July 1900 at age 54 while Hulda Schouten lived to age 86 dying in Nijmegen on 20 August 1933.

Jan Arnoldus attended elementary school, then high school, in Nijmegen. Jan and Hulda's marriage was not a happy one and they separated with Jan Arnoldus living with his mother to whom he was deeply attached. He learnt Dutch and German, becoming fluent in both languages, but his native language was German. He excelled at mathematics at high school and, not having qualifications to enter university, as a consequence entered the Military Academy in Breda. At this time students required a pass in a classical language in their final examination to enter university and Schouten had not studied any classical language. However, in 1901 he entered the Technische Hogeschool in Delft. He studied electrical engineering at the Technische Hogeschool and then for several years he was an electrical engineer. After a year of practical experience at Siemens in Berlin he graduated in 1908. He spent his holidays with his mother in Nijmegen where he was a member of the local rowing and sailing club. Here he met Maria Margaretha Backer, who had been a fellow student with Schouten at the high school, but by this time was a law student in Leiden. Maria had been born in Nijmegen on 1 May 1887; her parents were Jean Paul Frederic Backer, a cigar manufacturer, and Dorothea Cornelia Fik. Jan Arnoldus and Maria married on 21 January 1909; they had one son Jan Frederik and two daughters Hilde Margaretha Erica and Petronella Cornelia Maria.

Soon after the award of his electrical engineering degree from Delft, Schouten became an inspector at the Department of Local Electricity Works in Rotterdam. He made many trips abroad and was a contributor to the electrification of Rotterdam. However he came from a family with substantial amounts of money and when he inherited money in 1912, still having a deep love for mathematics, he gave up his electrical engineering job and went to Delft University to study mathematics. He was encouraged by Johan Antony Barrau (1874-1953) who had been a student of Diederik Johannes Korteweg and received a doctorate from the University of Amsterdam in 1907. At first Barrau advised Schouten but, after he left Delft for Groningen in 1913 to become Schoute's successor as professor of geometry, Jacob Cardinaal became Schouten's advisor. Jacob Cardinaal (1848-1922) had been a student of Jan de Vries and, in September 1893, had been appointed professor at the Polytechnic University in Delft. Cardinaal wrote the first Dutch book on kinematics in 1914. Schouten's doctoral thesis Grundlagen der Vektor- und Affinoranalysis, presented in 1914, was on tensor analysis, a topic he worked on all his life. That same year he became professor of mathematics at the Polytechnic University in Delft and held the post for nearly 30 years. He was rector of the University for the year 1938-39.

Dirk Struik became Schouten's assistant in 1917. He said [7]:-

Professor Schouten at the Technical University in Delft was looking for an assistant. Through Ehrenfest, he was told that this fellow Struik might be the right person. And he was. In 1917, I accepted an assistantship at Delft and became Schouten's assistant for seven years, from 1917 to 1924. There I learned my tensors. Schouten was, as were so many mathematicians at that time, deeply interested in the theory of relativity. I was never so much interested in quantum mechanics as in the theory of relativity, because the Delft is vectors and tensor, and so those things had become very familiar. Schouten was working on his form of what we now call tensor analysis. He called it afinial analysis. By and by, he introduced me to it. Over seven years, I became first, of course, the assistant, but later also the friend and collaborator of Schouten. And we published a good deal.

Albert Nijenhuis, who was a student of Schouten's submitting his thesis in 1952, summarises Schouten's life in the following words [1]:-

A descendant of a prominent family of shipbuilders, Schouten grew up in comfortable surroundings. He became not only one of the founders of the "Ricci calculus" but also an efficient organiser (he was a founder of the Mathematical Centre at Amsterdam in 1946) and an astute investor. A meticulous lecturer and painfully accurate author, he instilled the same standards in his pupils.

Of course, working on tensor analysis put Schouten in the exciting area of developments associated with the theory of relativity. He produced 180 papers and 6 books on tensor analysis, applying tensor analysis to Lie groups, general relativity, unified field theory, and differential equations. Influenced by Weyl and Eddington, Schouten investigated affine, projective and conformal mappings. Klein's Erlanger Programm of 1872 looked at geometry as properties invariant under the action of a group. This approach had a large influence on Schouten's approach to his topic.

In 1915 he discovered the Levi-Civita connection in Riemannian manifolds independently of Levi-Civita but since his paper only appeared in 1919, a year later than Levi-Civita's, he received no credit. This was despite arguing his case for priority explaining that, because of the problems caused by World War I he had not had access to journals to read the current papers. L E J Brouwer did not support Schouten and relations between the two were poor for a number of years until Weitzenböck got them to patch up their differences in 1929. Up to the point when he saw Giovanni Ricci's and Tulio Levi-Civita's work, Schouten's notation had been, by his own admission, difficult to understand but, once he saw their notation he accepted it immediately as simpler than his own. He published a monograph On the Determination of the Principle Laws of Statistical Astronomy in 1918 and his classic work on the Ricci calculus Der Ricci-Kalkül : Eine Einführung in die neueren Methoden und Probleme der mehrdimensionalen Differentialgeometrie in 1924. It is interesting to note that despite publishing a greatly expanded and updated version in 1954 (which we discuss below) a corrected reprinting of the original 1924 edition was published in 1978.

Schouten certainly did not work in isolation but collaborated and corresponded with other leading workers in the area. He interacted with Élie Cartan, Ludwig Berwald, Oswald Veblen, Alexander Friedmann, Arthur Eddington and Wolfgang Pauli writing joint papers with some of them. For example in 1924 he published Über die Geometrie der halb-symmetrischen Übertragungen jointly with Alexander Friedmann, and in 1926 he published two papers written jointly with Élie Cartan: On Riemaniann geometries admitting an absolute parallelism, and On the Geometry of the Group-manifold of Simple and Semi-simple Groups. He also acknowledged the ideas that came about through discussions with others, for example writing in his paper Über die Einordnung der Affingeometrie in die Theorie der höheren Übertragungen (1923) (see for example [2]):-

I owe thanks to Mr L Berwald in Prague, with whom I had an intensive exchange of ideas from September 1921, and who was so friendly as to give me his manuscripts before they went into print.

On a trip to the United States in 1931 he discussed his current work on spinors with Veblen. He attended the international conference on differential geometry organised by Benjamin Fedorovich Kagan which took place at Moscow University in 1934. In the following year the first of the two volumes of a monograph written in collaboration with Dirk Struik, Einführung in die Neuen Methoden der Differentialgeometrie, appeared. The second volume was published three years later in 1938. Although both authors appear on both volumes (each dedicated to Tullio Levi-Civita), the first volume is largely the work of Schouten while the second is largely the work of Struik.

Schouten, in collaboration with W van der Kulk, published Pfaff's Problem and Its Generalizations in 1949. Dirk Struik writes:-

This is a complete exposition of the classical theory of the Pfaffian equation and of the present results in the theory of systems of Pfaffian equations, to which the authors themselves have substantially contributed. The theme is presented in tensor language, by which a great unity of form and content is achieved. It embraces both the older theories of Jacobi and Mayer and the newer theories of Cartan, Kähler and the authors.

In 1951 he published Tensor Analysis for Physicists which was reviewed by N Coburn who begins his review:-

This text contains an excellent treatment of tensor analysis and applications to linear elasticity theory, dynamics, relativity, and quantum mechanics. Though the text does not assume a prior acquaintanceship with tensor theory, it is desirable that the reader possess some background in the subject. For such a reader as well as for the specialist, this text will furnish a wealth of useful and unified information.

Clive Kilmister, reviewing the same work, writes:-

The name gives little idea of the exhaustive and exact treatment, including such things as a complete discussion of the various groups involved and the use of non-holonomic co-ordinate systems. Rather it is meant to imply the author's attempt (largely successful) to give the fruits of his long experience of lecturing in the form of physical pictures of the concepts used at each stage.

We mentioned above Schouten's Ricci-calculus. An introduction to tensor analysis and its geometrical applications (1954). Geoffrey Walker writes:-

Since the publication of the author's 'Der Ricci-Kalkül' [1924] the subject of tensor calculus as applied to differential geometry has grown very considerably, and the present edition is more than a mere translation of the first. The author has played an active part in the development of the subject and results originally published in papers have also appeared in books written by the author in collaboration with others. The greater part of the work now appears however in its proper setting, and for the first time we have a comprehensive account of the work to date in certain well-defined fields.

Let us return to look at the later part of Schouten's career. In 1943, perhaps due to the pressures imposed by World War II, he became ill and underwent severe problems. Albert Nijenhuis wrote:-

In 1943 Schouten resigned the post, divorced his wife and remarried [to Hilda Bijlsma]. From then on, he lived in semiseclusion at Epe.

From 1948 until 1953 Schouten was professor of mathematics at the University of Amsterdam but he did not teach. He was a co-founder of the Mathematical Research Centre at Amsterdam in 1946 and was its director from 1950 to 1955. Schouten was president of the 1954 International Congress of Mathematicians at Amsterdam.

We end this biography by examining Schouten's role in the journal Compositio Mathematica because it sheds considerable light on his personality. The story of Compositio Mathematica's difficulties are told in the fascinating paper [11] from which we take most of the information described below. The journal had been run by L E J Brouwer and published by the House of Noordhoff, Groningen, but had to cease production in 1940 because of World War II. When it was proposed that publication restart in 1945, Noordhoff wanted to extend the editorial board and reduce Brouwer's role [11]:-

In order to get the journal under way again, Noordhoff and some mathematical colleagues called in the help of Schouten, who was the Dutch mathematician following Brouwer in seniority. Schouten's reputation as a geometer was beyond question, and he was considered one of the leading Dutch mathematicians. He had in 1943 resigned from his Delft chair, and withdrawn himself to a quiet part of the country, but his influence was still considerable and Noordhoff must have seen in him a valuable ally in the attempt to edge out Brouwer. Although Brouwer and Schouten had had their differences in the early 1920s (patched up in 1929 after the mediation of Weitzenböck), animosity was certainly not the motivation of Schouten to take Noordhoff's side. Schouten was one of the editors of 'Compositio' of the first hour; it was probably a sincere wish to restore 'Compositio' to its old glory, that made him an actor in the 'Compositio' affair.

Schouten wanted to keep Brouwer involved with Compositio Mathematica but only as one of several editors rather than having overall control. His negotiations with Brouwer were not successful however [11]:-

Unfortunately Schouten did not possess the tact needed to handle a mercurial person like Brouwer. His letters, obviously well-meant, were of the half-patronizing, half-schoolmastering kind that goes against the grain.

Having failed to persuade Brouwer to follow the route he favoured, Schouten tried to convince other members of the Committee of Administration, most of whom sided with Brouwer, that he was right. He sent a letter to the members:-

Apart from a recounting of the events, the letter contained a list of refutations of Brouwer's claims or suspicions. Some of Schouten's arguments and claims had a degree of plausibility, but if they contained some truth, certainly not the whole truth. In particular his protestation that he did not attempt to remove Brouwer seems a bit lame ...

It is clear that Schouten's motives were honourable and he wanted to do the best for Brouwer and the journal. However, like many others he found Brouwer difficult to deal with. Taking the initiative he went ahead with proposals to restart the journal without Brouwer's knowledge in late 1949. His proposals gave Brouwer a position as "honorary president" but, when Brouwer found out what was going on, threats of court action from Brouwer followed. There are many more twists to the story involving many mathematicians. These are detailed in [11] (which we strongly recommend to the reader) but in the end Schouten's scheme triumphed and Brouwer lost out never accepting the honorary role that was offered.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اتحاد كليات الطب الملكية البريطانية يشيد بالمستوى العلمي لطلبة جامعة العميد وبيئتها التعليمية

|

|

|