Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-02-20

Date: 2024-07-03

Date: 2024-03-20

|

Some requirements of a phonological feature system are as follows:

• the system should be relatively economical

• it should enlighten us about which combinations of features can go together universally, and therefore which segments and segmenttypes are universally possible. That is, many universal redundancy rules of the sort in (5) should not have to be written explicitly, as they will follow from the feature system.

• it should allow us to group together those segments and segment-types which characteristically behave similarly in the world’s languages.

Certain elementary phonetic features can be adopted without further question into our revised system: for instance, [±oral], [±lateral] and [±voice] do correspond to binary oppositions, and help us to distinguish classes of consonants in English and other languages. The main problems involve place and manner of articulation.

Turning first to manner of articulation, we might initially wish any sensible feature system to distinguish vowels from consonants. This is a division of which we are all intuitively aware, although that awareness may owe something to written as well as spoken language. Children learn early that, in the English alphabet, the vowel letters are , though these, alone and in combination, can signal a much larger number of vowel sounds. When challenged to write a word ‘without vowels’, English speakers might respond with spy or fly, but not type, although the

, though these, alone and in combination, can signal a much larger number of vowel sounds. When challenged to write a word ‘without vowels’, English speakers might respond with spy or fly, but not type, although the in all three cases indicates the vowel

in all three cases indicates the vowel , while the

, while the in type does not correspond to a vowel in speech (or indeed, to anything at all). Nonetheless, there is a general awareness that vowels and consonants form different categories integral to phonology and phonetics .

in type does not correspond to a vowel in speech (or indeed, to anything at all). Nonetheless, there is a general awareness that vowels and consonants form different categories integral to phonology and phonetics .

This binary opposition between vowels and consonants is not entirely clear-cut. For instance, vowels are almost always voiced: it is highly unusual for languages to have phonemically voiceless vowels, and those that do always have voiced ones too. However, there are also consonants which are almost always voiced: this is true of nasals, and also of approximants (like English /j w l r/). We might say that these consonants are closer to vowels than stops and fricatives, which can be either voiced or voiceless, and indeed often occur in pairs distinguished only by [+voice] – think of English /p b/, /t d/, /k g/, /f v/, /s z/.

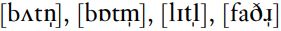

Similarly, vowels, form the essential, central part of syllables: it is possible to have a syllable consisting only of a vowel, as in I (or eye), a, oh, but consonants appear at syllable margins, preceding or following vowels, as in sigh, side, at, dough. Nonetheless, some consonants may become syllabic under certain circumstances. Nasals and approximants can be syllabic in English: for instance, in the second syllables of button, bottom, little (and father, for speakers who have an [ɹ] there), there is no vowel, only a syllabic consonant. You may think you are producing a vowel, probably partly because there is a vowel graph in the spelling; but in fact most speakers will move straight from one consonant to the next, although the syllabic consonant has its own phonetic character. In IPA notation, this is signaled by a small vertical line under the consonant symbol, giving . It is not possible for oral stops and fricatives to become syllabic in this way: in lifted, or horses, there must be a vowel before the final [d] or [z].

. It is not possible for oral stops and fricatives to become syllabic in this way: in lifted, or horses, there must be a vowel before the final [d] or [z].

This evidence seems to suggest that, on the one hand, we should distinguish all consonants from vowels. On the other hand, in many phonological processes in many different languages, the class of stops and fricatives behaves differently from the class of vowels, nasals, and approximant consonants, so that these two categories should be distinguishable too. Since these classifications cross-cut one another, it is clearly not possible to get the right results using a single binary feature, or indeed using any features proposed so far. For example, although we could describe the class of nasals, vowels and approximants as [– stop, – fricative], a negative definition of this kind does not really explain why they form a class, or what they have in common.

Many phonologists would use three features, the so-called major class features, to produce these classifications. First, we can distinguish consonants from vowels using the feature [±syllabic]; sounds which are [+syllabic] form the core, or nucleus, of a syllable, while [– syllabic] sounds form syllabic margins. Vowels are therefore [+syllabic], and all consonants [– syllabic], though some consonants (like English /m n l r/) may have [+syllabic] allophones in certain contexts. Second, the feature [±consonantal] distinguishes [+consonantal] oral stops, fricatives, nasals and ‘liquids’ (the cover term for /r/ and /l/ sounds), from [– consonantal] glides (like English /j/, /w/) and vowels. The crucial distinction here is an articulatory one: in [+consonantal] sounds, the airflow is obstructed in the oral cavity, either being stopped completely, or causing local audible friction; whereas for [– consonantal] sounds, airflow is continuous and unimpeded (remember that for nasal stops, although airflow continues uninterrupted through the nose, there is a complete closure in the oral cavity). Finally, [±sonorant] distinguishes nasals, vowels and all approximants from oral stops and fricatives; the former set, the sonorants, are characteristically voiced, while the latter, the obstruents, may be either voiced or voiceless.

As (7) shows, the combination of these three binary features actually distinguishes four major classes of segments.

However, we can produce further, flexible groupings, to reflect the fact that composite categories often behave in the same way phonologically. For example, vowels, nasals and all approximants are [+sonorant]; vowels and glides alone are [– consonantal]; and we can divide our earlier, intuitive classes of consonants and vowels using [±syllabic].

The introduction of these major class features resolves some of our earlier difficulties with manner of articulation; but we are still not able to distinguish stops from affricates or fricatives. To finish the job of accounting for manner, we must introduce two further features. The more important of these is [±continuant], which separates the oral and nasal stops, which are [– continuant] and have airflow stopped in the oral tract, from all other sounds, which are [+continuant] and have continuous oral airflow throughout their production. Second, the affricates /tʃ/ and (which we have rather been ignoring up to now) can be classified as a subtype of oral plosive; but the complete articulatory closure, for these sounds only, is released more gradually than usual, so that the affricates incorporate a fricative phase. The affricates are generally described as [+delayed release], while other stops are [– delayed release].

(which we have rather been ignoring up to now) can be classified as a subtype of oral plosive; but the complete articulatory closure, for these sounds only, is released more gradually than usual, so that the affricates incorporate a fricative phase. The affricates are generally described as [+delayed release], while other stops are [– delayed release].

Despite these advances in dealing with manner of articulations, there remain problems with place. Recall that, if all places of articulation are stated independently, a consonant which is [+alveolar] will also have to be listed as [– labial], [– dental], [– palatal], [– velar], and so on. To illustrate this problem, consider the different phonetic shapes of the prefix un- in (8).

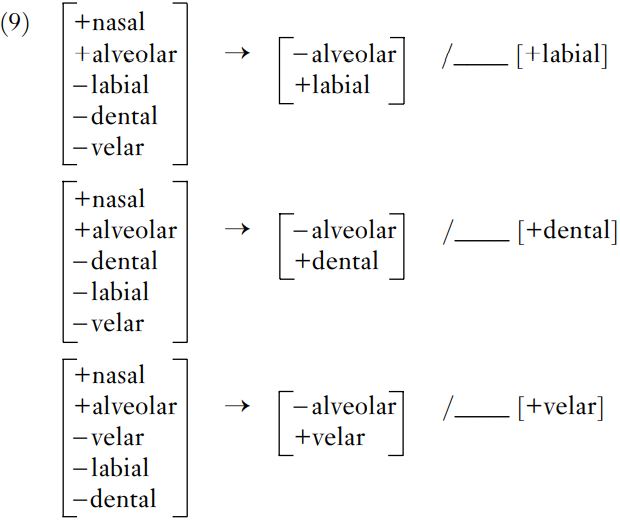

The prefix consonant is always nasal, but its place of articulation alters depending on the following segment. Before a vowel or an alveolar consonant, like [s], the nasal is alveolar; before a bilabial consonant like [p], it is bilabial; before a labio-dental like [f ], it is labio-dental  ; before a dental, it is dental [n]; and before a velar, in this case [k], it is also velar. We can write these generalizations as a series of phonological rules, as in (9). These rules have the same format as the redundancy rules proposed above; but instead of stating generalizations about necessary combinations of features, or excluded combinations, they summarize processes which take place in the structure of a particular language, in a certain context.

; before a dental, it is dental [n]; and before a velar, in this case [k], it is also velar. We can write these generalizations as a series of phonological rules, as in (9). These rules have the same format as the redundancy rules proposed above; but instead of stating generalizations about necessary combinations of features, or excluded combinations, they summarize processes which take place in the structure of a particular language, in a certain context.

... and so on

In these rules, the material furthest left is the input to the process, or what we start with – nasals with different place features in each case. The arrow means ‘becomes’, or technically ‘is rewritten as’; and there then follows a specification of the change that takes place. In (9), this always involves changing the place of articulation. Any feature which is not explicitly mentioned in the middle section of the statement is taken to be unchanged; so in the first rule, the consonant involved stays [+nasal, – dental, – velar], but changes its values for [±alveolar] and [±labial].

The rest of the statement following the environment bar / (which can be paraphrased as ‘in the following environment’) specifies the context where this particular realization appears. In (9), the environment always involves a following sound with a particular place of articulation: the line signals where the input fits into the sequence.

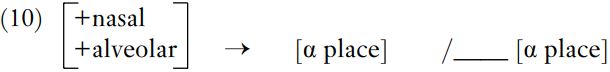

The problem is that this system of features, with several different places of articulation each expressed using a different feature, will lead to gross duplication in the statement of what is, in fact, a rather simple and straightforward generalization: /n/ comes to share the place of articulation of the following consonant. What seems to matter here is that the place of articulation of the output matches that of the conditioning context. If we were to regard all the place features as subdivisions of a higher-order feature ‘place’, we could state the whole rule as in (10).

This rule tells us that the place of articulation of the input consonant, an alveolar nasal, comes to match the place of the following segment, using a Greek letter variable. If the output and conditioning context also matched in voicing and nasality, for instance, further Greek letter variables could be introduced, so that the output and context would be specified as [α place, β voice, γ nasal]. A more advanced subpart of phonology, feature geometry, investigates which features might be characterized as variants of a superordinate feature like ‘place’ in this way.

Although recognizing a superordinate ‘place’ feature allows an economical statement of this particular process, we also need a way of referring to each individual place of articulation: after all, not all consonants will always undergo all rules in the same way, and indeed the input of (10) is still restricted to the alveolar nasal. It seems we must reject features like [±alveolar], [±velar], and turn again to a more economical, phonological feature set, which ideally should also help us group together those places of articulation which typically behave similarly cross-linguistically.

One generally accepted solution involves the two features [±anterior] and [±coronal]. [+anterior] sounds are those where the passive articulator is the alveolar ridge or further forward; this includes labial, labiodental, dental and alveolar sounds. [– anterior] sounds are produced further back in the vocal tract; for English, this will include postalveolar, palatal, velar and glottal sounds (and also, note, the labial-velars /w/ and/M/). For [+coronal] sounds, the active articulator is the tip, blade or front of the tongue, so including dental, alveolar, postalveolar and palatal consonants in English; conversely, [–coronal] sounds, such as labials, labio-dentals, labial-velars, velars and glottals, do not involve the front parts of the tongue. This system is undoubtedly economical, even though we require one further feature, [±strident], to distinguish fricatives like /s/ from /θ/: these will both be [– syllabic, +consonantal, – sonorant, +anterior, +coronal] in the feature system developed so far. [+strident] sounds in English are .

.

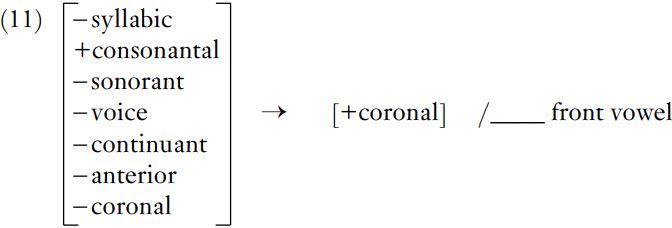

Rule (11) applies these features to English [k] and [c]. Note that it is common practice to exclude features which are not absolutely necessary to distinguish the sound or sounds referred to from others in the language: thus, although the input /k/ is strictly also [– nasal, – lateral, – delayed release, – strident], these redundant feature values need not be included, as /k/ is already uniquely identified from the features given.

Ideally, the explanation for the presence of a certain allophone in a certain context should be available in the rule itself. In (11), however, /k/ becomes [+coronal] before a front vowel; but the connection between [coronal] and [front] is obscured by the different descriptions conventionally used for vowels and consonants.

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي للقرآن الكريم يقيم جلسة حوارية لطلبة جامعة الكوفة

|

|

|