Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2025-04-09

Date: 2024-01-13

Date: 1-3-2022

|

Manner adverbials

The class of manner adverbs is fairly well defined, both syntactically and semantically. Jackendoff (1972) distinguished manner adverbs as a subclass of the verb phrase adverbs, those that appear sentence-finally but not sentenceinitially. This distinguishes them from modal and speech act adverbs such as possibly or frankly and from temporal and locative adverbials such as yesterday and in Rome. Syntactically, McConnell-Ginet (1982) takes manner adverbs to be not only associated with the VP but to be VP-internal. Clear cases of manner adverbs are such adverbs as quickly, slowly, carefully, violently, loudly, and tightly. Additionally, such prepositional phrases as with all his might and in a careful manner as well as instrumentals such as with a knife can also be taken to be a sort of manner modifier. We should note that many manner adverbs exhibit a limited type of regular polysemy (Jackendoff 1972), having a factive speaker-oriented meaning when sentence-initial and their more standard manner reading sentence-finally. This as illustrated in (1).

Although we will be concerned only with the manner reading here, we will discuss another sort of polysemy below, which may be related.

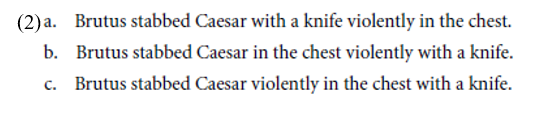

Semantically, manner adverbials are distinguished by a set of entailment properties (Davidson 1967; Parsons 1990). One of these is their scopelessness. As illustrated in (20), the order in which the adverbials appear doesn’t bear on the interpretation of the sentence: (2a), (2b), and (2c) are synonymous.

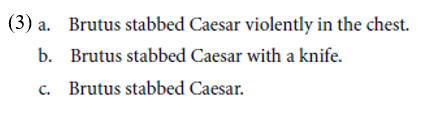

Additionally, manner modifiers have conjunctive interpretations, meaning that they can be dropped from a sentence, preserving its truth. If (2a) is true, so are (3a), (21b), and (3c).

This might seem to indicate that manner adverbial modification is simple intersective predicate modification (if something is a red book, it is red and it is a book). Crucially, however, the truth of (3a) and (3b) does not guarantee the truth of (2a) as would typically be the case for intersective modifiers (if something is red and it is a book, it is a red book). Intuitively, this is because (3a) and (3b) might refer to two different events: a violent stabbing in the chest (that was not done with a knife) and a stabbing with a knife (that was not violent). These three properties – which Landman dubbed “Permutation,”“Drop,” and “Non-Entailment” – characterize true Davidsonian manner modification, and show (as Parsons has argued extensively) that they cannot be treated as simply intersective predicate modification.

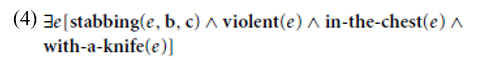

On the Davidsonian account, adverbial modifiers are taken to be event predicates which combine as co-predicates of the verb. How this modification proceeds, whether via a process of event-identification (Higginbotham 2000) or simple functional application (Parsons 1990) will not concern us here. On any Davidsonian account, the logical representation of (2a) is something like the following:

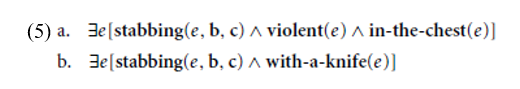

One of the central appeals of Davidsonianism is that elementary facts about first order logic appear to describe exactly the semantic behavior of manner adverbial modifiers analyzed in this way. Given the analysis in (4), it is clear that the order of combination does not matter. Furthermore, since (4) entails both (5a) and (5b) – the analyses of (3a) and (3b) respectively – but is not entailed by them, it is clear why Drop and Non-Entailment hold.

The fact that the properties of Permutation, Drop, and Non-Entailment follow directly from Davidson’s assumption that verbs and manner adverbials are event predicates is certainly strong evidence for the account.

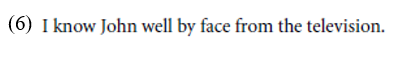

Turning this around, Parsons (1990, 2000), Landman (2000), andMittwoch (2005) have all suggested that if sentences exhibit this trio of Davidsonian properties, then these sentences should be given a Davidsonian analysis. Landman, for example, bases his argument for the Davidsonian analysis of the verb know on what he takes to be the entailments associated with example (6).

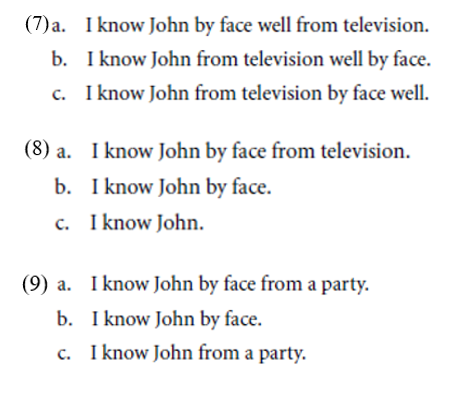

Specifically, Landman claims that (6) entails each of (7a–c) – the “Permutations,” and each of (8a–c) – the “Drops,” and furthermore that the conjunction of (9b) and (9c) does not entail (9a) – the “Non-Entailment.”

If these claims are correct, the argument is a very strong one for providing this state verb (and perhaps state verbs in general) with an underlying Davidsonian state argument. In the following section, we will evaluate these claims.

|

|

|

|

دراسة تكشف "مفاجأة" غير سارة تتعلق ببدائل السكر

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أدوات لا تتركها أبدًا في سيارتك خلال الصيف!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تؤكد الحاجة لفنّ الخطابة في مواجهة تأثيرات الخطابات الإعلامية المعاصرة

|

|

|