Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 3-3-2022

Date: 3-3-2022

Date: 8-3-2022

|

Polydefiniteness/D-spreading in Modern Greek

Like English, Modern Greek shows prenominal restrictive adjectives that cannot typically appear postnominally. This is illustrated in the contrast between (1a) and (1b).1

But postnominal APs can be licensed in Modern Greek definite DPs via the phenomenon of “determiner spreading,” in which the definite determiner is essentially duplicated between each of the modifiers. Thus either (2a) or (2b) is possible (Androutsopoulou 1994, 1995; Alexiadou and Wilder 1998; Kolliakou 1998; Marinis and Panagiotidis 2004).

Interestingly, the possibility of D-spreading imposes at least two constraints. First, the adjective must be interpreted restrictively. Second, only intersective/ predicating as are permitted. These facts are illustrated in (3–5). In (3a) (from Marinis and Panagiotidis 2004) the prenominal A ikani ‘competent’ appearing in the boldfaced DP is interpreted either restrictively or unrestrictively. Thus DP can be understood as referring only to the competent researchers, or to all the researchers (who are understood to be competent). By contrast in (3b), with D-spreading, only the former, restrictive interpretation is available for the postnominal A.

The second constraint – that only intersective/predicating as can appear – is demonstrated in (4) and (5) (from Alexiadou and Wilder 1998). (4a, b) show that the non-intersective adjective ipotithemenos ‘alleged’ can appear in prenominal position, but not in the D-spreading construction. Similarly, for (5a, b), which involve the non-predicating nationality adjective italiki ‘Italian.

The facts of Modern Greek raise simple and immediate questions: How does D-spreading license a postnominal A that would have otherwise been disallowed? And why must A be read restrictively/predicatively? Again the D-shell analysis offers an attractive answer.

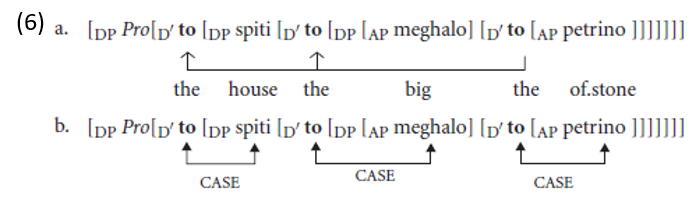

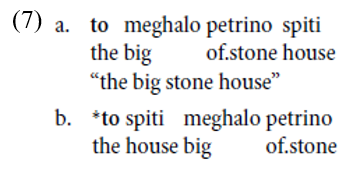

On our proposal, multiple modifiers involve multiple DP-shells through which D raises recursively. Suppose that as D raised through the DP-shells, it were permitted to leave behind a copy whose formal but not semantic features were active. Assuming, as we have, that D checks the Case features on its complements, we would expect a single additional D Case to become available for each copy of D, allowing an AP to remain in situ for each copy.

We suggest that this is exactly what is happening in the Greek polyde finiteness construction. When definite D raises, it has the option of leaving copies behind (6a); this licenses exactly one AP/NP in each shell by each copied head (6b).

In the case where no copies are left, no Case is assigned to the APs/NPs, and they must raise (7a, b).

1 Chris Kennedy (p.c.) raises the interesting question of whether verb-copying is available for case marking in the verbal domain as well. The phenomenon of verb serialization in West African languages suggests a possible general analogy.

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

سماحة السيد الصافي يؤكد ضرورة تعريف المجتمعات بأهمية مبادئ أهل البيت (عليهم السلام) في إيجاد حلول للمشاكل الاجتماعية

|

|

|