Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-10-03

Date: 4-3-2022

Date: 2024-09-13

|

Most business documents are written after the problem they address has been solved. The purpose of some documents, however, is to tell the reader the steps the writer will go through to find the solution to the problem. Consulting proposals and project plans fall into this category.

Both documents require you to define the problem in the introduction, and both are generally structured around the steps in the analysis. Both spell out for a prospective client (or a requesting manager) your understanding of what his problem is and how you propose to go about solving it. If the proposal or project plan is accepted, you will then conduct an analysis into the causes of the problem, and write a report embodying your conclusions and recommendations.

In the case of a consulting proposal, you are generally also establishing a contractual agreement that tells the client what he is buying, how much it will cost, when it will be finished, and who will do what in the process. As a way of ensuring that these items get included in the document, most consulting firms have adopted a standard set of headings around which to structure their proposals:

Introduction

Background

Objectives and Scope

Issues

Technical Approach

Work Plan and Deliverables

Benefits

Firm Qualifications and Related Experience

Timing, Staffing, and Fees

The trouble with writing around such headings is that they encourage the writer to make lists under each section. The lists tend to overlap and thus work to obscure your actual thinking.

For example, the information that would go under Introduction, Background and Objectives and Scope has to do with the definition of the problem, while that under Issues, Technical Approach, and Work Plan and Deliverables actually deals with the steps in solving the problem. And the value of a separate Benefits section has always eluded me, given that the benefit is that you will solve the client's problem, which I presume was the objective in the first place.

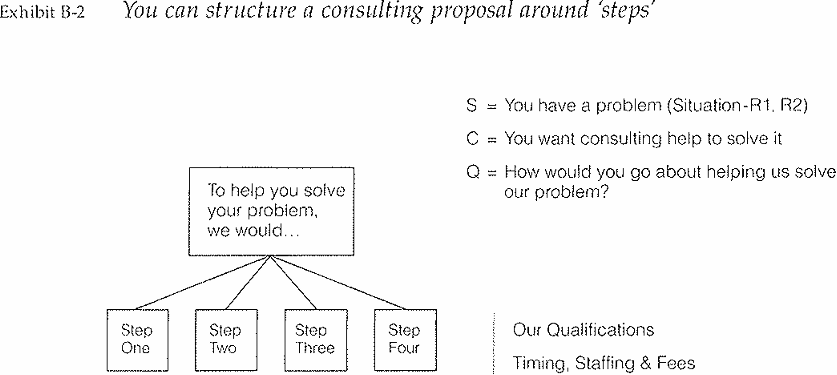

Consequently, as noted in, Fine Points of Introductions, I recommend a structure like that shown in Exhibit B-2, in which the introduction explains the problem and the document itself is structured either around the approach (as is shown here) or around a set of reasons about why the client should hire you, as shown in Exhibit B-3. (Project Plans arc always structured around the process).

The consulting firm's qualifications and information about timing, staffing, and fees, are included in a proposal, but are considered outside the structure of the thinking.

As to whether you want to structure to show the steps in the process or to explain the reasons for hiring you, that depends usually on the competitive nature of the proposal. If it is a client you have worked with before, and the proposal is simply a confirmation of what you have agreed to do for him this time, I suggest structuring around the steps in the process. If however, it is a competitive situation, you probably want to structure around the reasons the client should hire you, as shown in Exhibit B-3.

The major difference is that in the second approach you begin with a short paragraph that reads something like this:

We were delighted to meet with you to discuss your plans to market your software to developing countries. This document represents, our proposal for helping you develop an appropriate marketing strategy. It consists of:

- Our understanding of the market opportunity available to you

- The approach we would take to helping you develop a strategy for taking full advantage of that opportunity

- Our experience in carrying out this kind of assignment in the past

- Our business arrangements.

The first section would then explain the problem in detail, using the Sittwtion-R1-R2 structure and making sure to address the specific hot buttons or agendas1 of the client decision makers that are expected to be factors in the selection process. The second section would set out the approach, while the third would highlight the specific or unique expertise you bring to solving the problem.

To give you a sense of the process, Exhibits B-4 and B-5 show the problem definition and pyramid for a U.S. telephone company that wanted to sell its software to developing countries. The facts were as follows:

The company had for years developed its own business and administrative software. Some of what it had developed in prior years was now obsolete for their purposes, but it saw a possible demand for this kind of software in developing or third-world countries. It consequently had decided to set up a joint venture to build product families on distinctive competencies, and sell these to attractive segments.

However, the company had never sold to these markets before, and did not know what the market segments were, let alone which were the attractive ones. It had consequently decided to hire a consulting firm to help it determine which were the attractive markets for its software products.

These facts can be laid out in the problem-definition framework like this:

Then, reading from left to right, you would transform them into a pyramid that looks like this:

1 For a superb discussion of, assessing client concerns, see "Writing Winning Proposals" by Joseph Romano and Richard and Shervin Freed (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1995)

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|