Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-11-06

Date: 2023-05-13

Date: 1-2-2022

|

A class of predicates which are similar in some respects to unaccusative predicates are passive predicates. Traditional grammarians maintain that the bold-printed verbs in sentences such as the (a) examples in (53)–(55) below are in the active voice, whereas the italicized verbs in the corresponding (b) sentences are in the passive voice (and have the status of passive participles):

There are four main properties which differentiate passive sentences from their active counterparts. One is that passive (though not active) sentences generally require the auxiliary BE. Another is that the main verb in passive sentences is in the passive participle form (cf. seen/stolen/taken), which is generally homophonous with the perfect-participle form. A third is that passive sentences may (though need not) contain a by-phrase in which the complement of by plays the same thematic role as the subject in the corresponding active sentence: for example, hundreds of passers-by in the active structure (53a) serves as the subject of saw the attack, whereas in the passive structure (53b) it serves as the complement of the preposition by (though in both cases it has the thematic role of EXPERIENCER argument of see). The fourth difference is that the expression which serves as the complement of an active verb surfaces as the subject in the corresponding passive construction: for example, the attack is the complement of saw in the active structure (53a), but is the subject of was in the passive structure (53b). We will focus on the syntax of the superficial subjects of passive sentences (setting aside the derivation of by-phrases).

Passive predicates resemble unaccusatives in that alongside structures like those in (56a)–(58a) below containing preverbal subjects they also allow expletive structures like (56b)–(58b), in which the italicized argument can be postverbal (providing it is an indefinite expression):

How can we account for the dual position of the italicized expression in such structures?

The answer given within the framework outlined here is that a passive subject is initially merged as the thematic complement of the main verb (i.e. it originates as the complement of the main verb as in (56b)–(58b) and so receives the θ-role which the relevant verb assigns to its complement), and subsequently moves from VP-complement position into TP-specifier position in passive sentences such as (56a)–(58a). On this view, the derivation of sentences like (56) will proceed as follows. The noun corruption merges with the quantifier any to form the QP any corruption. The resulting QP then merges with the preposition of to form the PP of any corruption. This PP in turn merges with the noun evidence to form the NP evidence of any corruption. The resulting NP is merged with the negative quantifier no to form the QP no evidence of any corruption. This QP is merged as the complement of the passive verb found (and thereby assigned the thematic role of THEME argument of found) to form the VP found no evidence of any corruption. The VP thereby formed is merged with the auxiliary was forming the T-bar was found no evidence of any corruption. The auxiliary [T was] carries an [EPP] feature requiring it to have a specifier. This requirement can be satisfied by merging the expletive pronoun there in spec-TP, deriving the TP There was found no evidence of any corruption. Merging this TP with a null complementizer marking the declarative force of the sentence will derive the structure shown in simplified form in (59) below:

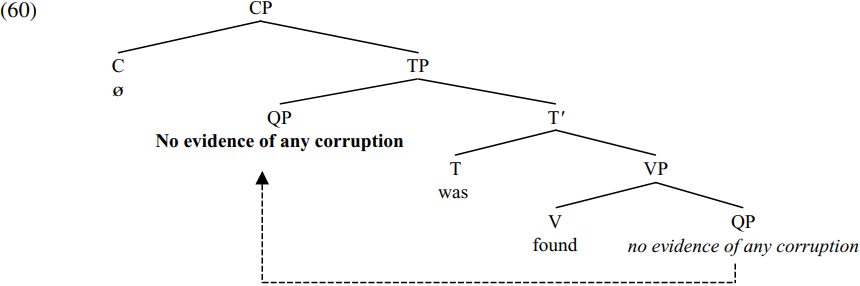

However, an alternative way of satisfying the [EPP] feature of T is not to merge there in spec-TP but rather to passivise the QP no evidence of any corruption – i.e. to move it from being the thematic object of found to becoming the structural subject of was. Merging the resulting TP with a null complementizer which marks the sentence as declarative in force derives the CP shown in simplified form in (60) below (with the dotted arrow showing the movement which took place on the TP cycle):

The arrowed movement operation (traditionally called passivisation) by which QP moves from thematic complement position into structural subject position turns out to be a particular instance of the more general A-movement operation which serves to create structural subjects (i.e. to move arguments into spec-TP in order to satisfy the [EPP] feature of T). Note that an assumption implicit in the analyses in (59) and (60) is that verb phrases headed by intransitive passive participles remain subjectless throughout the derivation, because the T constituent was is the head which requires a structural subject by virtue of its [EPP] feature, not the verb found (suggesting that it is functional heads like T and C which trigger movement, not lexical heads like V).

In the case of (56a) No evidence of any corruption was found, the whole of the QP no evidence of any corruption is spelled out in the bold-printed spec-TP position in (60) at the head of the movement chain, and all the material in the italicized VP-complement position at the foot of the movement chain is deleted. However, we saw that some structures in which a moved noun has a prepositional complement may allow discontinuous spellout, with the noun and any preceding expressions modifying it being spelled out at the head of the movement chain, and its prepositional or clausal complement being spelled out at the foot of the movement chain. Discontinuous spellout is also permitted in (60), allowing for the possibility of the quantifier no and the noun evidence being spelled out in the bold-printed position at the head of the movement chain, and the PP of any corruption being spelled out in the italicized VP-complement position at the foot of the movement chain, so deriving the structure associated with the sentence in (61) below:

Sentences such as (61) thus provide us with empirical evidence that passive subjects originate as complements, on the assumption that of any corruption is a remnant of the preposed complement no evidence of any corruption.

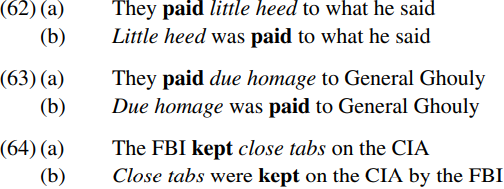

Further evidence that passive subjects originate as complements comes from the distribution of idiomatic nominals like those italicized below:

In expressions such as pay heed/homage to and keep tabs on, the verb pay/keep and the noun expression containing heed/tabs/homage together form an idiom. Given our arguments that idioms are unitary constituents, it is apparent that the bold-printed verb and the italicized noun expression must form a unitary constituent when they are first introduced into the derivation. This will clearly be the case if we suppose that the noun expression originates as the complement of the associated verb (as in (62a)–(64a)), and becomes the subject of the passive auxiliary was/were in (62b)–(64b) via passivisation/A-movement.

Additional evidence that passive subjects are initially merged as complements comes from quantifier stranding in West Ulster English structures such as the following (from McCloskey 2000, p. 72):

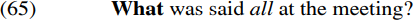

Recall from our earlier discussion of sentences like (37) that McCloskey argues that stranded quantifiers modifying wh-expressions are left behind via movement of the wh-expression without the quantifier. This being so, sentences such as (65) provide evidence that what all originates as the complement of the passive participle said (with what subsequently being passivized on its own, stranding all) – and more generally, that passive subjects are initially merged as thematic objects.

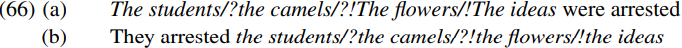

A claim which is implicit in the hypothesis that passive subjects originate as thematic objects is that the subjects of active verbs and the complements of passive verbs have the same thematic function. Evidence that this is indeed the case comes from the traditional observation that the two are subject to the same pragmatic restrictions on the choice of expression which can occupy the relevant position, as we see from sentences such as the following (where ?, ?! and ! mark increasing degrees of pragmatic anomaly):

We can account for this if we suppose that pragmatic restrictions on the choice of admissible arguments for a given predicate depend jointly on the semantic properties of the predicate and the thematic role of the argument: it will then follow that two expressions which fulfil the same thematic role in respect of a given predicate will be subject to the same pragmatic restrictions on argument choice.

Since passive subjects like those italicized in (66a) originate as complements, they will have the same θ-role (and hence be subject to the same pragmatic restrictions on argument choice) as active complements like those italicized in (66b).

We can arrive at the same conclusion (that passive subjects originate as thematic complements) on theoretical grounds. It seems reasonable to suppose that principles of UG correlate thematic structure with syntactic structure in a uniform fashion: this assumption is embodied in the Uniform Theta Assignment Hypothesis/UTAH argued for at length in Baker (1988). Given UTAH, it follows that two arguments which fulfil the same thematic function with respect to a given predicate will occupy the same initial position in the syntax. Hence if passive subjects have the same -role as active objects, it is plausible to suppose that passive subjects originate in the same VP-complement position as active objects.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|