تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

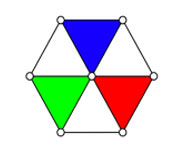

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

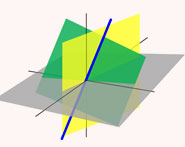

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 8-1-2018

Date: 8-1-2018

Date: 1-1-2018

|

Died: 20 August 2001 in Bournemouth, England

Fred Hoyle's parents were Ben Hoyle and Mabel Pickard. Mabel's father had died when she was a small child. As a young girl she had worked in a mill in Bingley and had saved up enough money to study music at the Royal Academy of Music in London. After training there she decided not to perform but she taught music in schools before marrying Ben. Like Mabel, Ben had worked in a mill. He had been forced to leave school at the age of eleven since his family were too poor to support his education any longer.

Fred's parents bought 4 Milnerfield Villas on the outskirts of the village of Gilstead in West Yorkshire in 1910 and they were living there when World War I broke out in 1914. Their first child was Fred who was born at 4 Milnerfield Villas just before his father was conscripted into the British army, choosing to join the Machine Gun Corps. Quite why he chose this is unclear for the chances of survival were extremely slim and one might have thought that, with a wife and young child, he would have tried to maximise his chances. Obviously he did not think in this way, and against all the odds he survived the war. It was an extremely difficult time for Fred's mother who had to bring up her young child in difficult circumstances, living in continual fear that she would receive a letter telling her that her husband had been killed. Mabel earned a little money by playing the piano for the silent films in Bingley cinema. She also provided Fred with his early education, in particular teaching him numbers.

After World War I ended Ben returned to civilian life and he set up a cloth business (particularly dealing in wool) in Bradford, the nearest large town. At first the business did well and in 1920 it was decided to send Fred to a small private school. However there was a sharp downturn in business in general in 1921 and by the time that Fred started school his father's cloth business was suffering badly. The start of Fred's school education marked the beginning of a difficult time [2]:-

Between the ages of five and nine, I was perpetually at war with the educational system. My father always deferred to my mother's judgement in the several crises of my early educational career, because she had been a schoolteacher herself ... events would suggest that my mother was unreasonably tolerant of my obduracy. But, precisely because she had been a teacher herself, my mother could see that I made the best steps when I was left alone.

Fred only attended the private school for a few weeks in July 1921 before his father decided to temporarily give up his failing cloth business and move to Rayleigh in Essex. There Fred entered a school near Thundersley and immediately made friends with a classmate. The pair worked out a way to play truant but before they had much chance to try their scheme out Fred's family returned to Gilstead in November 1921 on hearing that there were problems with the people to whom they had let their house. Back home, Fred was returned to his first school in January 1922:-

I returned to the same private school as before, but I returned no longer an innocent child prepared to have irrelevant knowledge poured into my head by the old beldame who ran the place.

In March Fred put his truancy scheme into practice and while his parents believed he was at school, the school believed that he was ill at home. After a couple of months his parents found out what was going on, but he was allowed to choose a new school instead of returning. He decided to attend Morning Road School in Bingley but there he performed rather poorly in tests that were carried out. This was hardly surprising since he had avoided school most of the time up till then, and soon he was avoiding school again partly through genuine illness and partly through pretending to be ill during the winter of 1923-24.

Despite his attempts to avoid formal education Hoyle did show interest in educating himself. He read a chemistry book which belonged to his father and found an interest in the subject which would last a lifetime. However problems at Morning Road School prompted another move and he began to attend Eldwick school from September 1924. After Hoyle narrowly missed out on a scholarship for grammar school, an appeal was entered and he scraped through beginning his studies at Bingley Grammar School in September 1926. His war with the education system had ended, and although there were still many educational problems ahead, he now approached education with a much more positive attitude.

In 1927 Bingley town library acquired a copy of Eddington's Stars and Atoms and Hoyle read it avidly. By the end of his first year at the Grammar School, he had progressed from his entry position of 16th in the class to top the class. His interest in chemistry continued and as he neared the end of his school career he decided to go to Leeds University to study chemistry there. Taking the scholarship examinations in September 1932 he narrowly missed out. Unable to study at university without a scholarship, he returned to Bingley Grammar School but instead of working steadily through the year with the aim of gaining a scholarship to Leeds at the second attempt, Hoyle decided to aim at a Cambridge University Scholarship. It was an ambitious scheme but one which he felt would at least give him practice at taking such examinations.

Bingley Grammar School did not really have the teaching resources to bring Hoyle rapidly up to Cambridge Scholarship standard, but the mathematics teacher did his very best and gave him lessons in his own home. Hoyle sat the scholarship examinations in Emmanuel College Cambridge in December 1932:-

If a miracle happened and I won something in Cambridge, well and good. I would be glad to accept it, but my real aim ... was to prove to myself that the efforts of the past three months had really improved my standards.

Hoyle's performance was good in physics and chemistry but, as he expected, his preparation for mathematics had been weak and the mathematics paper dragged him down. He missed the scholarship standard but decided to take the scholarship examinations at Pembroke College, Cambridge in March 1933. This time his performance was better and he did make the scholarship standard, but the College did not have scholarships for everyone who made the standard, and again Hoyle missed out. However, he could now get into Cambridge by winning a scholarship in the Yorkshire scholarship competition and he was successful in this in the summer of 1933, with now mathematics as his best subject.

In the autumn of 1933 Hoyle entered Emmanuel College, Cambridge, intending to read for a degree in science. His tutor was a mathematician, P W Wood, who told him at their first meeting that his mathematics was not good enough to read for a degree in science so he advised that Hoyle take Part I of the Mathematical Tripos which would put him in a good position to study science after that with a better grounding in mathematics. So Hoyle embarked on the one year mathematics course, entering at the bottom level of the slow stream. His aim was to get himself into the middle of the slow stream by the time he took Part I of the Mathematical Tripos and indeed he achieved better than this for he was in the top quarter of this slow stream by the end of year one.

Having achieved his aim in mathematics, it would have been natural for Hoyle to move into the science course as he had intended. However, he was always one to rise to a challenge and having progressed so well it was natural for him to wonder how much higher he could climb in mathematics. There was another argument which told him to carry on with mathematics which was that the great Cambridge scientists like Newton, Maxwell, Kelvin, Eddington and Dirac had all been mathematicians. He decided to carry on and entered his second year of study of mathematics at the bottom of the fast stream. Again he progressed well and ended the year well into the top half of the class.

Hoyle was taught by some outstanding people while he was an undergraduate at Cambridge. For example Born taught him quantum mechanics, Eddington taught him general relativity, and he was also taught by Dirac. He was placed in the top ten when he took the Mathematical Tripos in 1936 and was awarded the Mayhew Prize as the best student in applied mathematics. Continuing to study at Cambridge, his research was supervised by Rudolf Peierls and his career went from strength to strength with the award of the top Smith's Prize in 1938 and then, with Peierls and R H Fowler as referees, he was awarded a prestigious Goldsmith's Exhibition. By this time he was being supervised by Maurice Pryce who took over when Peierls went to the chair of Applied Mathematics at Birmingham. In 1939 Hoyle published a major paper on Quantum electrodynamics in the Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society.Although Hoyle had completed the work for a Ph.D. by then he was persuaded by Pryce not to submit (the Ph.D. was new to Cambridge and Pryce did not approve of it).

Although his research was in applied mathematics, it was through the problem of accretion of gas by a large gravitating body which Ray Lyttleton discussed with him that Hoyle's interests turned towards mathematical problems in astronomy. With everything going his way, with election to a Fellowship at St John's in May 1939 for work on beta decay and receiving a highly prestigious award from the Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, his career was suddenly put on hold with the outbreak of World War II [2]:-

War would change everything. It would destroy my comparative affluence, it would swallow my best creative period, just as I was finding my feet in research.

Shortly after the outbreak of war Hoyle married Barbara Clark on 28 December 1939. They had one son Geoffrey (with whom Hoyle would have several joint publications) and one daughter Elizabeth. During the war Hoyle worked for the Admiralty on radar, doing most of this work in Nutbourne. He had little time for research in astronomy but continued collaboration with Lyttleton when it proved possible (one occasion being when he had leave in 1942 for the birth of his first child Geoffrey). During his time with the Admiralty Hoyle worked with Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold and he discussed astronomy with them in spare moments. These three would later propose "steady-state cosmology" for which Hoyle is probably best known.

In 1944 he visited the USA because of his work on radar and while there he worked out what was going on with the atomic bomb project. This led him to think of nuclear reactions, and out of this came one of his most important ideas about how the elements were created. He returned to Cambridge at the end of the war as a Junior Lecturer in Mathematics. His teaching duties were to give a geometry course and a statistical mechanics course in 1945-46. In 1945 he published On the integration of the equations determining the structure of a star which discussed the most advantageous way of integrating the equations of stellar equilibrium. In the spring of 1946 he wrote his important paper which developed from the ideas he had about the creation of the elements The Synthesis of the Elements from Hydrogen which appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

After three years as a Junior Lecturer in Mathematics, Hoyle was promoted to Lecturer in Mathematics at Cambridge and given tenure. He stopped teaching geometry, teaching instead courses on Electricity and Magnetism, and on Thermodynamics. His range of publications broadened with works on many different topics and at many different levels. In 1948 he published two papers on steady-state cosmology. His first move into explaining science to a general audience came in 1950. He broadcast five astronomy lectures on the Third Programme (now called Radio 3). These were extremely popular and were often repeated, with versions being broadcast in the United States and a book Nature of the Universe being published based on the lectures. It was in the last of these five lectures that Hoyle coined the phrase "Big Bang" for the creation of the universe. Although now accepted by most scientists, the term was actually meant to be a scornful description of the creation theory which Hoyle did not accept.

In 1957 Hoyle published his first science fiction novel The Black Cloud which achieved much praise and has since become a classic (about a dozen of his 40 books have been on science fiction) [1]:-

... he wrote [science fiction] successfully for more than three decades, winning a devoted following. His most famous novel was 'October The First Is Too Late', in which Britain and Hawaii remain in 1966, the Americas are switched back to the 15th century and the Soviet Union exists in a future time when the surface of the Earth is a plate of glass.

Hoyle also wrote the television serial 'A for Andromeda' and the children's play' Rockets in Ursa Major'. When this was performed in 1962 at the Mermaid Theatre, one critic wrote: "Seldom can scientific mumbo-jumbo have sounded so convincing." This writing, Hoyle believed, complemented his serious work, in the middle of which he would stop to indulge in what he called "whimsical fantasies." He was convinced that really important discoveries were most likely to come from an exercise of creative imagination.

He became Plumian Professor of Astrophysics and Natural Philosophy on 1 October 1958 after Harold Jeffreys retired, a position which he held until he resigned in 1972. During his tenure of the chair continued to publish many important works such as his collaborative work with William Fowler, Nuclear cosmochronology published in 1960 in the Annals of Physics which described how the observed ratios of the abundance of different isotopes of uranium and thorium can be used to determine a cosmical time-scale. In 1966 Hoyle founded the renowned Institute of Theoretical Astronomy at Cambridge and was its Director until 1972.

The events leading up to Hoyle's resignation from Cambridge in 1972 are recounted in [2]. He explained his reasons in a letter to Lovell (see [5]):-

I do not see any sense in continuing to skirmish on a battlefield where I can never hope to win. The Cambridge system is effectively designed to prevent one ever establishing a directed policy - key decisions can be upset by ill-informed and politically motivated committees. To be effective in this system one must for ever be watching one's colleagues, almost like a Robespierre spy system. If one does so, then of course little time is left for any real science.

Following this he made his home in the Lake District but he continued to come up with interesting, and often unconventional, theories such as those concerning Stonehenge, panspermia (that the origin of life on Earth must have involved cells which arrived from space), Darwinism, palaeontology, and viruses from space. I [EFR] was lucky enough to hear Hoyle speak about his theory that Stonehenge was built as an eclipse predictor. It was an inspiring talk which, like so much of Hoyle's work, really made one think about things in a new light. Hoyle continued to publish up to the end of his life with Mathematics of evolutionappearing in 1999 and A Different Approach to Cosmology: From a Static Universe through the Big Bang towards Reality (written jointly with G Burbidge and Narlikar) being published in 2000.

Hoyle received many honours. He was knighted in 1972. He was elected to many academies and learned societies including the Royal Society of London (1957), the National Academy of Sciences of the United States (1969), the American Philosophical Society (1980), the American Academy of Arts and Science (1964), and the Royal Irish Academy (1977). He received many honours including: the United Nations Kalinga Prize in 1968, the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1968, the Bruce Medal from the Astronomical Society of the Pacific in 1970, the Royal Medal of the Royal Society in 1974, the Dag Hammarskjöld Gold Medal, the Karl Schwartzchild Medal, the Balzan Prize in 1994, and the Crafoord Prize awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1997. Typical of the citations he received for such awards was that of the Royal Medal which states that his:-

... enormous output of ideas are immediately recognised as challenging to astronomers generally... his popularisation of astronomical science can be warmly commended for the descriptive style used and the feeling of enthusiasm about his subject which they succeed in conveying.

Wickramasinghe writes in [7]:-

... Hoyle sought to answer some of the biggest questions in science: How did the Universe originate? How did life begin? What are the eventual fates of planets, stars and galaxies? More often than not he discovered answers to such questions in the most unsuspected places. For instance he discovered that the secret of how stars evolve lay in a certain property of the carbon nucleus, a property (a resonance) that was not discovered until Fred himself had pointed to its absolute necessity.

Fred believed that, as a general rule, solutions to major unsolved problems had to be sought by exploring radical hypotheses, whilst at the same time not deviating from well-attested scientific tools and methods. ...

Fred Hoyle had no respect for the boundaries between scientific disciplines which were artificial social constructs that often stood in the way of a proper comprehension of the cosmos. The Universe does not respect the differences between physics, chemistry and biology, he would say, and his career in astronomy progressively embraced all these disciplines.

Martin Rees has written this tribute:-

Hoyle's enduring insights into stars, nucleosynthesis, and the large-scale universe rank among the greatest achievements of 20th-century astrophysics. Moreover, his theories were unfailingly stimulating, even when they proved transient. He will be remembered with fond gratitude not only by colleagues and students, but by a much wider community who knew him through his talks and writings.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|