تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

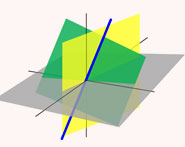

الجبر

الجبر

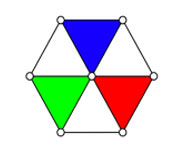

الهندسة

الهندسة

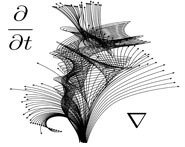

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 3-9-2017

Date: 20-8-2017

Date: 17-8-2017

|

Died: 18 June 1980 in Warsaw, Poland

Kazimierz Kuratowski's father, Marek Kuratowski was a leading lawyer in Warsaw. To understand what Kuratowski's school years were like it is necessary to look a little at the history of Poland around the time he was born. The first thing to note is that really Poland did not formally exist at this time.

Poland had been partitioned in 1772 and the south was called Galicia and under Austrian control. Russia controlled much of the rest of the country and in the years prior to Kuratowski's birth there had been strong moves by Russia to make "Vistula Land", as it was called, be dominated by Russian culture. In a policy implemented between 1869 and 1874, all secondary schooling was in Russian. Warsaw only had a Russian language university after the University of Warsaw became a Russian university in 1869. From 1906, however, the Underground Warsaw University was set up to provide a Polish university education for those prepared to risk teaching and learning in this illegal institution. Galicia, although under Austrian control, retained Polish culture and was often where Poles from "Vistula Land" went for their education.

When Kuratowski was nine years old the policy of Russian schooling was softened, but although Polish language schools were allowed, a student could not proceed from such a secondary school to university without taking the Russian examinations as an external candidate. As a consequence most Poles in "Vistula Land" at this time went abroad for their university education. Some went to Galicia where, although under Austrian control, Polish education still flourished. Kuratowski, however, when he left secondary school decided that he wanted to become an engineer. The University of Glasgow, in Scotland, had an engineering school with a long established history, the chair of engineering being established in 1840. It rightly appeared to Kuratowski as an outstanding place to study engineering.

After Kuratowski made the decision to study in Glasgow, he matriculated there as a student in October 1913. Interestingly, Sneddon relates in [15]:-

He must have feared that his name would present difficulty to his fellow students for it appears in the registry of the Ordinary Class in Mathematics as Casimir Kuratov.

At the end of his first year Kuratowski was awarded the Class Prize in Mathematics. He then studied chemistry at the Technical College during the summer and returned to Poland for a holiday before starting his second year of study. However, back in Poland in August 1914 at the outbreak of World War I, returning to Scotland became impossible for Kuratowski. Although his education was disrupted, one benefit to mathematics was that Kuratowski could no longer study engineering and mathematics would gain enormously.

In August 1915 the Russian forces which had held Poland for many years withdrew from Warsaw. Germany and Austria-Hungary took control of most of the country and a German governor general was installed in Warsaw. One of the first moves after the Russian withdrawal was the refounding of the University of Warsaw and it began operating as a Polish university in November 1915. Kuratowski was one of the first students to study mathematics when the university reopened. He attended seminars given by Janiszewski and Mazurkiewicz in Warsaw before the end of the war. He writes in [2]:-

As early as 1917 [Janiszewski and Mazurkiewicz] were conducting a topology seminar, presumably the first in that new, exuberantly developing field. The meeting of that seminar, taken up to a large extent with sometimes quite vehement discussions between Janiszewski and Mazurkiewicz, were a real intellectual treat for the participants.

There were two others on the staff at the University of Warsaw who were also to have a major influence on Kuratowski. One was Lukasiewicz, a professor of philosophy who worked on mathematical logic. The second person, who arrived in 1918, was Sierpinski. In fact the first paper which Kuratowski wrote was On the definitions in mathematics, written in 1917, which was a consequence of discussions which he had while attending Lukasiewicz's seminar. After graduating in 1919, Kuratowski undertook his doctoral studies working under Janiszewski and Mazurkiewicz.

In 1921 Kuratowski was awarded his doctorate, but sadly one of his supervisors Janiszewski had died in 1920. Janiszewski had been the leader in a move to set up the new journal Fundamenta Mathematicae and the first volume, which appeared in 1920, contained a joint paper Sur les continus indécomposable by Janiszewski and Kuratowski.

Kuratowski was appointed as a professor at the Technical University of Lvov in 1927. In [4] Ulam, who began his university undergraduate career the year Kuratowski began lecturing in Lvov, wrote:-

He was a freshman professor, so to speak, and I was a freshman student. From the very first lecture I was enchanted by the clarity, logic, and polish of his exposition and the material he presented. ... Soon I could answer some of the more difficult questions in the set theory course, and I began to pose other problems. Right from the start I appreciated Kuratowski's patience and generosity in spending so much time with a novice.

The mathematicians of Lvov did a great deal of mathematical research in the cafés of the city. The Scottish Café was the most popular with the mathematicians in general but not with Kuratowski who, together with Steinhaus (according to Ulam [4]):-

... usually frequented a more genteel tea shop that boasted the best pastry in Poland.

This café was Ludwik Zalewski's Confectionery at 22 Akademicka Street. It was in the Scottish Café, however, that the famous Scottish Book consisting of open questions posed by the mathematicians working there came into being. Kuratowski (and Steinhaus) sometimes joined their colleagues in the Scottish Café but he had left Lvov before the mathematicians began writing down the problems in the Scottish Book.

At Lvov, however, Kuratowski worked with Banach and they answered some fundamental problems on measure theory. Ulam, who had become Banach's research student also worked with them. As Arboleda writes in [1]:-

This was a beautiful example of scientific collaboration and understanding, and of the ability to organise and encourage creative activity at its height.

Kuratowski retained his links with Warsaw while in Lvov, returning each summer to his house outside the capital. In 1934 he left Lvov and became professor of mathematics at the University of Warsaw. He was to spend the rest of his career at the University of Warsaw although he became involved in mathematical activities which saw him travelling world-wide. It was now that Kuratowski began to devote his energies to the cause of Polish mathematics rather than to give all his efforts to his research. He was still extremely active in research, however, and while spending a month at Princeton in 1936 he wrote a joint paper with von Neumann. During his time in the United States he also made contact with Robert Moore's topology group, meeting mathematicians who he would keep in contact with for many years.

Janiszewski had made the case for Polish mathematics concentrating on its areas of strength when he wrote his report at the end of World War I. In 1936 a committee was set up by the Polish Academy of Learning to look at the way forward for Polish science. Kuratowski became secretary to the mathematics committee and his report was made in 1937. He recommended that the time had come to go beyond the era of concentrating on strengths, proposed by Janiszewski, and to develop across the whole of the mathematical spectrum. In particular there was a need:-

... to raise applied mathematics to such a standard that it can fulfil its tasks as required by other branches of science, as well as those tasks connected with the problems of the country.

The recommendations of the report to set up two research institutes, one for pure mathematics and one for applied mathematics, may have been implemented had it not been for the political situation. After the German invasion of Poland in 1939 life there became extremely difficult. There was a strategy by the invaders to put an end to the intellectual life of Poland and to achieve this they sent many academics to concentration camps and murdered others. The Poles had experience of surviving such attacks, however, and they employed the same tactics as they had during the period of Russian domination and organised an underground university in Warsaw. Kuratowski risked his life to teach in this illegal educational establishment through the war. He writes in [2]:-

Almost all our professors of mathematics lectured at these clandestine universities, and quite a few of the students then are now professors or docents themselves. Due to that underground organisation, and in spite of extremely difficult conditions, scientific work and teaching continued, though on a considerably smaller scale of course. The importance of clandestine education consisted among others in keeping up the spirit of resistance, as well as optimism and confidence in the future, which was so necessary in the conditions of occupation. The conditions of a scientist's life at that time were truly tragic. Most painful were the human losses.

Between the two world wars Poland had made a remarkable leap forward in mathematical teaching and research. At the end of World War II the whole educational system was destroyed and had to be completely rebuilt. It was Kuratowski who now took on the role of leader in this rebuilding process and, through the Polish Mathematical Society of which he was president for eight years immediately following the war, he set about arguing for the implementation of the recommendations of his 1937 report.

The two research institutes, one for pure mathematics and one for applied mathematics, were merged into a plan for a single mathematics institute and accepted in 1948. Kuratowski was appointed the Director of the Mathematical Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences in 1949. Despite being 53 years of age when appointed, Kuratowski held this position of director for 19 years. He held other positions of importance in the Polish scientific scene. For example, he served as a vice president of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Kuratowski also played a major role in the publishing of mathematics in general and Polish mathematics in particular. He served on the editorial board of Fundamenta Mathematicae from 1928, replacing Sierpinski as editor-in-chief in 1952 and continuing in this role for the rest of his life. He was also one of the founders and an editor of the important Mathematical Monographs series. He contributed the third volume in this series with his monograph on topology which we will mention again below.

As an ambassador for Polish mathematics, Kuratowski did a remarkable job with many foreign visits and lecture tours. He lectured in London (1946), Geneva (1948), many universities in the United States during 1948-49, Prague, Berlin, Budapest, Amsterdam, Rome, Peking (1955), Canton (1955), Shanghai (1955), Agra (1956), Lucknow (1956), and Bombay (1956). All this was during the Stalinist era when travel was restricted, and after travel became easier Kuratowski did indeed take full advantage with many visits to western Europe, Britain, USA, and Canada.

Kuratowski's main work was in the area of topology and set theory. He used the notion of a limit point to give closure axioms to define a topological space. In 1922 [1]:-

... he used Boolean algebra to characterise the topology of an abstract space independently of the notion of points. Subsequent research showed that, together with Felix Hausdorff's definition of topological space in terms of neighbourhoods, the closure operator yielded more fertile results than the axiomatic theories based on Maurice Fréchet's convergence (1906) and Frigyes Riesz's point of accumulation (1907).

Other major contributions by Kuratowski were to compactness and metric spaces. He was the author of Topologie, referred to above, which was the crowning achievement of the Warsaw School in point set topology. The first volume of this work was the major source on metric spaces for several decades.

His 1930 work on non-planar graphs is of fundamental importance in graph theory, he showed that a necessary and sufficient condition for a graph G to be planar is that it does not contain a subgraph homeomorphic to either K5 or K3,3.

His work in set theory considered a function as a set of ordered pairs and this made the function notion as proposed by Frege, Charles Peirce and Schröder redundant. He also considered the topology of the continuum, the theory of connectivity, dimension theory, and answered measure theory questions.

Kuratowski was honoured with prizes and election to academies. The USSR Academy of Sciences, the Hungarian Academy, the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the Academy of the German Democratic Republic, the Academy of Sciences of Argentina, the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, the Academy of Arts and Letters of Palermo, and the Royal Society of Edinburgh all elected him to membership. He received honorary degrees from many universities including Glasgow, the Sorbonne, Prague and Wroclaw.

Ulam, in the preface which he wrote to [2], sums up Kuratowski's contribution in the following words:-

Professor Kuratowski stands out not only as a great figure in mathematical research, but in his ability, so rare among original scientists, to organise and direct schools of mathematical research and education.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ووفد من جامعة البصرة يبحثان سبل تعزيز التعاون المشترك

|

|

|