تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

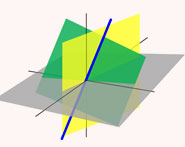

الهندسة

الهندسة

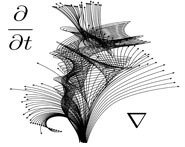

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 21-10-2015

Date: 21-10-2015

Date: 21-10-2015

|

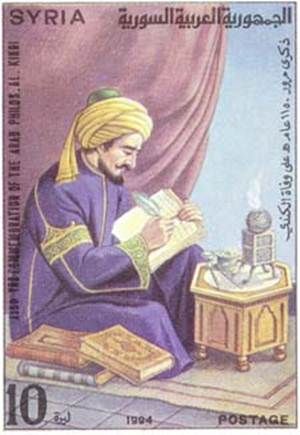

Born: about 801 in Kufa, Iraq

Died: 873 in Baghdad, Iraq

Al-Kindi was born and brought up in Kufa, which was a centre for Arab culture and learning in the 9th century. This was certainly the right place for al-Kindi to get the best education possible at this time. Although quite a few details (and legends) of al-Kindi's life are given in various sources, these are not all consistent. We shall try to give below details which are fairly well substantiated.

Al-Kindi was born and brought up in Kufa, which was a centre for Arab culture and learning in the 9th century. This was certainly the right place for al-Kindi to get the best education possible at this time. Although quite a few details (and legends) of al-Kindi's life are given in various sources, these are not all consistent. We shall try to give below details which are fairly well substantiated.

According to [3], al-Kindi's father was the governor of Kufah, as his grandfather had been before him. Certainly all agree that al-Kindi was descended from the Royal Kindah tribe which had originated in southern Arabia. This tribe had united a number of tribes and reached a position of prominence in the 5th and 6th centuries but then lost power from the middle of the 6th century. However, descendants of the Royal Kindah continued to hold prominent court positions in Muslim times.

After beginning his education in Kufah, al-Kindi moved to Baghdad to complete his studies and there he quickly achieved fame for his scholarship. He came to the attention of the Caliph al-Ma'mun who was at that time setting up the "House of Wisdom" in Baghdad. Al-Ma'mun had won an armed struggle against his brother in 813 and became Caliph in that year. He ruled his empire, first from Merv then, after 818, he ruled from Baghdad where he had to go to put down an attempted coup.

Al-Ma'mun was a patron of learning and founded an academy called the House of Wisdom where Greek philosophical and scientific works were translated. Al-Kindi was appointed by al-Ma'mun to the House of Wisdom together with al-Khwarizmi and the Banu Musa brothers. The main task that al-Kindi and his colleagues undertook in the House of Wisdom involved the translation of Greek scientific manuscripts. Al-Ma'mun had built up a library of manuscripts, the first major library to be set up since that at Alexandria, collecting important works from Byzantium. In addition to the House of Wisdom, al-Ma'mun set up observatories in which Muslim astronomers could build on the knowledge acquired by earlier peoples.

In 833 al-Ma'mun died and was succeeded by his brother al-Mu'tasim. Al-Kindi continued to be in favour and al-Mu'tasim employed al-Kindi to tutor his son Ahmad. Al-Mu'tasim died in 842 and was succeeded by al-Wathiq who, in turn, was succeeded as Caliph in 847 by al-Mutawakkil. Under both these Caliphs al-Kindi fared less well. It is not entirely clear whether this was because of his religious views or because of internal arguments and rivalry between the scholars in the House of Wisdom. Certainly al-Mutawakkil persecuted all non-orthodox and non-Muslim groups while he had synagogues and churches in Baghdad destroyed. However, al-Kindi's [6]:-

... lack of interest in religious argument can be seen in the topics on which he wrote. ... he appears to coexist with the world view of orthodox Islam.

In fact most of al-Kindi's philosophical writings seem designed to show that he believed that the pursuit of philosophy is compatible with orthodox Islam. This would seem to indicate that it is more probably that al-Kindi became [1]:-

... the victim of such rivals as the mathematicians Banu Musa and the astrologer Abu Ma'shar.

It is claimed that the Banu Musa brothers caused al-Kindi to lose favour with al-Mutawakkil to the extent that he had him beaten and gave al-Kindi's library to the Banu Musa brothers.

Al-Kindi was best known as a philosopher but he was also a mathematician and scientist of importance [3]:-

To his people he became known as ... the philosopher of the Arabs. He was the only notable philosopher of pure Arabian blood and the first one in Islam. Al-Kindi "was the most leaned of his age, unique among his contemporaries in the knowledge of the totality of ancient scientists, embracing logic, philosophy, geometry, mathematics, music and astrology.

Perhaps, rather surprisingly for a man of such learning whose was employed to translate Greek texts, al-Kindi does not appear to have been fluent enough in Greek to do the translation himself. Rather he polished the translations made by others and wrote commentaries on many Greek works. Clearly he was most influenced most strongly by the writings of Aristotle but the influence of Plato, Porphyry and Proclus can also be seen in al-Kindi's ideas. We should certainly not give the impression that al-Kindi merely borrowed from these earlier writer, for he built their ideas into an overall scheme which was certainly his own invention.

Al-Kindi wrote many works on arithmetic which included manuscripts on Indian numbers, the harmony of numbers, lines and multiplication with numbers, relative quantities, measuring proportion and time, and numerical procedures and cancellation. He also wrote on space and time, both of which he believed were finite, 'proving' his assertion with a paradox of the infinite. Garro gives al-Kindi's 'proof' that the existence of an actual infinite body or magnitude leads to a contradiction in [7]. In his more recent paper [8], Garro formulates the informal axiomatics of al-Kindi's paradox of the infinite in modern terms and discusses the paradox both from a mathematical and philosophical point of view.

In geometry al-Kindi wrote, among other works, on the theory of parallels. He gave a lemma investigating the possibility of exhibiting pairs of lines in the plane which are simultaneously non-parallel and non-intersecting. Also related to geometry was the two works he wrote on optics, although he followed the usual practice of the time and confused the theory of light and the theory of vision.

Perhaps al-Kindi's own words give the best indication of what he attempted to do in all his work. In the introduction to one of his books he wrote (see for example [1]):-

It is good ... that we endeavour in this book, as is our habit in all subjects, to recall that concerning which the Ancients have said everything in the past, that is the easiest and shortest to adopt for those who follow them, and to go further in those areas where they have not said everything ...

Certainly al-Kindi tried hard to follow this path. For example in his work on optics he is critical of a Greek description by Anthemius of how a mirror was used to set a ship on fire during a battle. Al-Kindi adopts a more scientific approach (see for example [1]):-

Anthemius should not have accepted information without proof ... He tells us how to construct a mirror from which twenty-four rays are reflected on a single point, without showing how to establish the point where the rays unite at a given distance from the middle of the mirror's surface. We, on the other hand, have described this with as much evidence as our ability permits, furnishing what was missing, for he has not mentioned a definite distance.

Much of al-Kindi's work remains to be studied closely or has only recently been subjected to scholarly research. For example al-Kindi's commentary on Archimedes' The measurement of the circle has only received careful attention as recently as the 1993 publication [10] by Rashed.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم التربية والتعليم يكرّم الطلبة الأوائل في المراحل المنتهية

|

|

|