Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 17/11/2022

Date: 1-8-2022

Date: 2023-10-28

|

Having presented an account of phases which is broadly consistent with Chomsky’s recent work, we turn here to reflect on the nature of phases. One issue which arises out of our discussion concerns the relation between EPP-hood and phasehood. In the system, the relation seems relatively clear (at least for heads which trigger A-bar movement operations like wh-movement): complementizers and transitive light verbs are phase heads and can have an [EPP] feature triggering A-bar movement, whereas intransitive light-verbs which have no external argument are not phase heads and cannot have an [EPP] feature triggering A-bar movement. Note, however, that this leads to a potential asymmetry: both transitive and intransitive complementizers alike have an [EPP] feature, but only transitive (not intransitive) light verbs have an [EPP] feature. Below, I present a piece of evidence calling into question the assumption that intransitive vPs cannot have an [EPP] feature: the evidence suggests that just as a wh-expression extracted out of transitive vP moves through spec-vP, so too a wh-expression extracted out of an intransitive vP also moves through spec-vP.

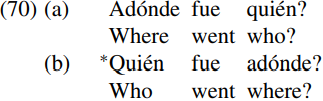

The relevant evidence comes from intransitive multiple wh-questions such as the following in Spanish (kindly provided by Cris Lozano, who trialled them on native speakers of both Peninsular Spanish and Mexican Spanish, and obtained unanimous, clearcut grammaticality judgments):

(Imagine a scenario for such sentences in which a friend says to you ‘President Phat Khat went to New York yesterday’, and you say ‘Sorry, I didn’t hear you’ and then go on to produce (70).) Unlike what happens in English, Spanish requires adonde ´ (literally ‘to.where’, but here glossed simply as ‘where’) to be preposed, not quien´ ‘who’. Why should this be?

Let’s suppose that sentence (70a) is derived as follows. The unaccusative verb (which is ultimately spelled out as) fue ‘went’ is merged with its GOAL argument adonde ´ ‘where’ to form the V-bar fue adonde ´ ‘went where’ and the resulting V-bar is then merged with its THEME argument quien´ ‘who’ to form the VP quien´ fue adonde ´ ‘who went where’. This VP is in turn merged with an intransitive light verb, forming the structure shown below:

The light verb has a strong (affixal) V-feature, and so attracts the verb fue ‘went’ to move from V to v. If we suppose that the light verb also has [WH, EPP] features, it would be expected to attract the closest wh-expression to move to spec-vP. In terms of the c-command definition of closeness given in (60) above, quien´ ‘who’ is closer to the light verb than adonde ´ ‘where’, and hence we’d expect quien´ ‘who’ to move to spec-vP. But the contrast in (70) suggests that the light verb is unable to attract quien´ ‘who’ and instead attracts adonde ´ ‘where’. This suggests that quien´ ‘who’ must be inactive for A-bar movement for some reason. But why?

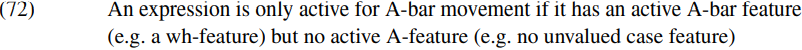

The answer we shall suggest here is that:

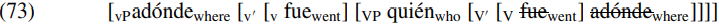

The pronoun quien´ ‘who’ carries a case feature which is as yet unvalued at the stage of derivation shown in (71) above, and hence – given (72) – is inactive for an A-bar movement operation like wh-movement. If we suppose that the light verb attracts the closest wh-expression which is active for A-bar movement, it follows that the light verb will attract the locative pronoun adonde ´ ‘where’ to move to spec-vP, so deriving the structure shown in simplified form in (73) below (strikethrough being used to indicate constituents which will ultimately receive a null spellout):

The resulting vP is then merged with a strong T constituent which triggers raising of verb fue ‘went’ to T, and which agrees with and assigns nominative case to the subject quien´ ‘who’, so deriving:

The TP thereby formed is then merged with a strong interrogative C constituent which carries [TNS, WH, EPP] features. The affixal [TNS] feature of C triggers raising of the verb fue ‘went’ from T to C, and its [WH, EPP] features trigger movement of the closest active wh-expression to spec-CP. Since adonde ´ ‘where’ is closer to C than quien´ ‘who’ in (73), it is the former which moves to spec-CP, so deriving the overt structure shown in highly simplified form below:

And (75) is the structure of (70a) Adonde fue qui´en? ´ ‘Where did who go?’

There are several points of interest which arise from the derivation sketched above. The first is that in order to derive (70a) we need to assume that adonde ´ ‘where’ moves to spec-vP at the stage of derivation shown in (73) above: if this did not happen, both quien´ ‘who’ and adonde ´ ‘where’ would remain in situ until C is introduced into the derivation, and since quien´ ‘who’ would then be the closest wh-expression to C, we would wrongly predict that (70b) ∗Quien´ fue adonde? ´ ‘Who went where?’ is the eventual outcome. More generally, the derivation outlined above leads us to suppose that intransitive vPs as well as their transitive counterparts can have an [EPP] feature which triggers successive-cyclic wh-movement through spec-vP.

We might therefore follow Legate (2002) in concluding that not only transitive vPs but also intransitive vPs are phases. However, such a conclusion is incompatible with the derivation for sentences like (70a) outlined here. The key point to note is that at the stage of derivation represented in (74) above, T must be able to agree with and assign nominative case to the subject quien´ ‘who’ in spec-VP; but if an intransitive vP is a phase, the Phase Impenetrability Condition (1) will block quien´ ‘who’ from serving as a goal for an external T probe, thereby leaving the uninterpretable case feature on quien´ ‘who’ and the uninterpretable person/number features on fue ‘went’ unvalued and undeleted, and causing the derivation to crash. In other words, the conclusion our discussion of sentences like (70) leads us to is that both intransitive and transitive light verbs can have [WH, EPP] features, but that only transitive vPs are phases. This leads to dissociation between the [EPP] property and phasehood. However, such a dissociation is found elsewhere (e.g. T in English has an [EPP] feature but is not a phase head).

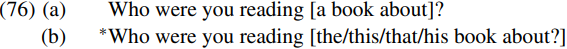

Having looked at the relation between EPP-hood and phasehood, let’s now turn to explore the question of whether (in addition to CPs and transitive vPs) other types of constituent may also be phases. Our discussion throughout here so far has looked at the role of phases in the derivation of clausal structures, raising the question of whether there are also phases within the nominal domain. Reflecting on this question, Chomsky (1999, p. 11) writes: ‘Considerations of semantic-phonetic integrity, and the systematic consequences of phase identification, suggest that the general typology should include among phases nominal categories.’ Since phases do not allow any element to be extracted out of their domain, one way of accounting for contrasts like that in (76) below would be to suppose that definite DPs are phases:

We could then say that extraction of who out of the bracketed indefinite DP in (76a) is permitted because indefinite DPs are not phases, whereas extraction of who out of the definite DP in (76b) is not permitted because definite DPs are phases, and the Phase Impenetrability Condition (1) prevents who from being extracted out of the NP book about who which is the complement of the head D of the bracketed definite DP. (It should be noted that Chomsky 1999, p. 36, fn. 28 envisages the possibility that ‘phases include DPs’.)

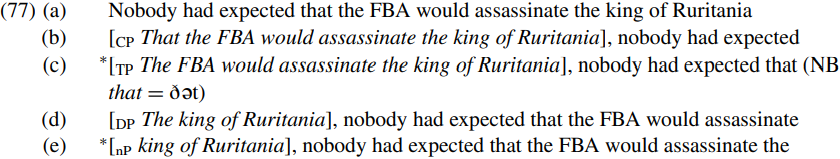

The assumption that definite DPs are phases would offer us a new perspective on the following contrasts which we first looked:

In (77b–e) a variety of constituents have been preposed to highlight them. In (77b) the fronted expression is a CP which functions as the complement of a non-phasal head (namely the verb expected) and can be preposed under appropriate discourse conditions. In (77c) the fronted constituent is a TP which is the complement of a phasal head (namely the complementizer that), and preposing the relevant TP violates the Phase Impenetrability Condition (1). In (77d), the fronted expression is a DP which is the complement of a non-phasal head (namely the verb assassinate), and hence there is no prohibition on extraction. But in (77e), extraction of an nP complement of the determiner the results in ungrammaticality: we can account for this if we suppose that definite DPs are phases, since the Phase Impenetrability Condition will prevent extraction of the nP king of Ruritania because this is the complement of the phase head the. The reason why the head of a phase does not allow extraction of its complement (or of any element contained within its complement) is that at the end of a phase, the complement of a phase head undergoes transfer in accordance with (7i) and thereafter becomes syntactically inactive.

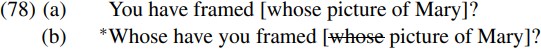

The hypothesis that definite DPs are phases also offers us an interesting account of why (in languages like English) possessives cannot be extracted out of their containing DPs – as we see from the contrast between the echo question in (78a) below and its wh-movement counterpart in (78b):

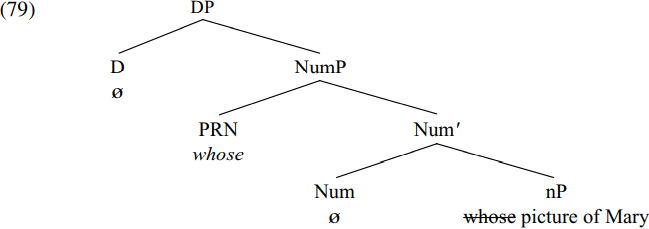

Suppose that the bracketed DP in (78a) has the structure shown in (79) below, with whose superficially positioned in the specifier position within a NumP/Number Phrase projection:

We can then account for why whose cannot be extracted out of the overall DP in (79) by supposing that a definite DP is a phase, and that at the end of the DP cycle, the NumP complement of DP undergoes transfer, with the result that whose cannot be extracted out of its containing NumP projection.

However, such an analysis is not entirely without posing problems. One such is how we account for the fact that the whole DP containing whose can undergo wh-movement:

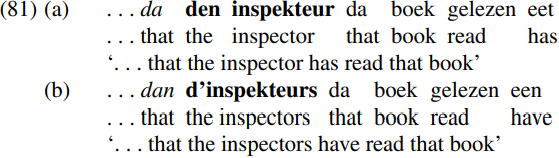

The head v of vP and the head C of CP in (80) contain [WH, EPP] features which attract the wh-pronoun whose (along with the pied-piped material picture of Mary) to move through spec-vP into spec-CP. But if a definite DP is a phase, the problem we face is that at the end of the DP cycle, the NumP constituent containing whose will undergo transfer to the PF and semantic components, and so the [WH] feature on whose will not be visible to either v or C. One apparent way of seemingly resolving this problem (without abandoning the assumption that a definite DP is a phase) would be to suppose that D has an [EPP] feature triggering movement of whose into spec-DP: but this would leave us with no phase-based account of why whose cannot subsequently be extracted from its containing DP in sentences like (78b). An alternative possibility (which would again allow us to continue to maintain that definite DPs are phases) would be to suppose that whose remains in spec-NumP but the wh-feature on whose percolates onto the head D of DP, perhaps via some form of agreement parallel to agreement between a complementizer and a subject in a number of languages. In this connection, it is interesting to note Haegeman’s (1992, p. 47) claim that in West Flemish ‘the complementizer of the finite clause agrees in person and number with the grammatical subject of the sentence it introduces’. Haegeman (1994, p. 131) provides the following illustrative data:

The italicized complementizer has the form da when the bold-printed subject is third person singular, but dan when it is third person plural. If the head C of CP can agree in person and number with the specifier of its TP complement in structures like (81), it seems no less plausible to suppose that the head D of DP can agree in wh-ness with the specifier of its NumP complement in structures like (79). This would mean that the overall DP would have a wh-marked head and hence could undergo wh-movement.

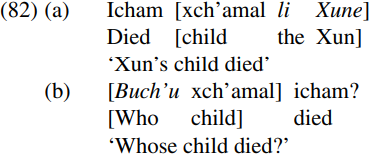

Some evidence which is consistent with the view that definite DPs are phases comes from observations about the pied-piping of possessive phrases in Tzotzil made by Aissen (1996). She notes that although (italicized) possessors are generally positioned postnominally in Tzotzil as in (82a) below, when the possessor is an interrogative pronoun, it is moved to the front of the DP containing it, and the whole containing DP is then moved to the front of the interrogative clause, as in (82b):

The interrogative possessor in (82b) appears to move to spec-DP, and this movement is consistent with the view that DP is a phase, since if the possessor remained in situ within the NP complement of D, PIC would prevent C from attracting the wh-pronoun (since NP and its constituents would be impenetrable to C). Movement of the interrogative pronoun to the edge of DP makes it accessible to C.

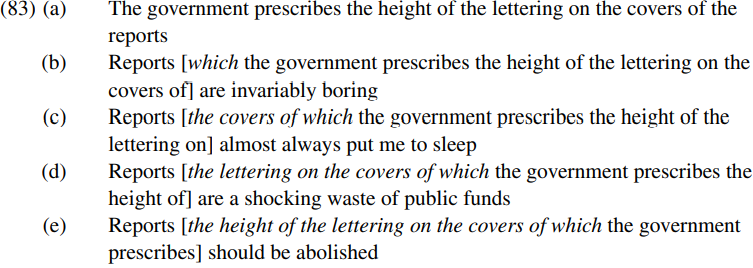

However, there are a number of problems which arise if we assume that definite DPs are phases. For example, Ross (1967) noted that corresponding to a sentence like (83a) below, we find a range of types of relative clause including like those bracketed in (83b–e):

Prior to wh-movement, the nominal containing the wh-pronoun which has the structure shown in skeletal form below:

This means that the italicized wh-moved expression in (83) has been moved out of three containing definite DPs in (83b), out of two in (83c), and out of one in (83d) – and all of these movements would be predicted to be impossible if definite DPs were phases.

One way round this problem (consistent with maintaining that definite DPs are indeed phases) would be to posit that (like other phase heads such as C and transitive v), the head D constituent of DP can have an [EPP] feature which allows it to attract a DP to move to its specifier position. This would mean that which in (83b) moves first to become the specifier of the DP the covers of which, then to become the specifier of the DP the lettering on the covers of which, then to become the specifier of the DP the height of the lettering on the covers of which, from there moving into spec-vP and thence into the spec-CP position which it occupies in (83b). An interesting question raised by the assumption that D can have an [EPP] feature triggering movement to its specifier position is why the NP king of Ruritania in (76e) cannot move to become the specifier of the DP the king of Ruritania, and from there go on to move to the front of the overall clause. The answer is that the Remerger Constraint prevents the NP king of Ruritania from moving to spec-DP, since this constraint tells us that a constituent which is merged as the complement of a given head cannot subsequently be remerged as its specifier. If DP is a phase, movement of the NP directly out of its containing DP will be blocked by the Phase Impenetrability Condition – as we saw earlier. (For an insightful discussion of extraction out of DPs, see Davies and Dubinsky 2003.)

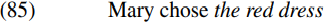

However, the assumption that definite DPs are phases poses problems for casemarking. In languages with a richer case morphology than English, in a transitive sentence such as:

the accusative case which the transitive (light verb associated with the) verb chose assigns to its complement is carried not only by the (counterpart of the) determiner the but also by the (counterparts of the) adjective red and the noun dress. But if DP is a phase, its complement red dress will have been sent for transfer at the end of the DP cycle, leaving only the head D of DP visible for case-marking by the transitive (light) verb. Such an analysis would mean that we have to posit a PF operation which Sch¨utze (2001) terms case-spreading to ensure that the case assigned to the determiner the in the syntax spreads to the adjective red and the noun dress in the morphology. What this means is that we end up with an asymmetric account of case-marking under which determiners are assigned case via agreement in the syntax, but adjectives and nouns are assigned case via a separate PF operation of case-spreading (which might be the analogue of the traditional notion of concord). Moreover, if the adjective red and the noun dress each have an unvalued and undeleted case feature at the end of the derivation, the derivation will crash at the semantics interface (since the undeleted case feature cannot be assigned any semantic interpretation). So, for an analysis along the lines sketched out here to be workable, we would have to abandon the claim that uninterpretable features must be deleted in the syntax and instead suppose that uninterpretable features are intrinsically uninterpretable and so (like phonological features) are not handed over to the semantic component at the end of the relevant part of the syntactic derivation. On this alternative view, the only requirement for an unvalued, uninterpretable feature would be that it should be assigned a value (in the syntax or morphology) in order to be spelled out at PF. As should be apparent from our brief discussion here, the potential repercussions of taking DPs to be phases are considerable.

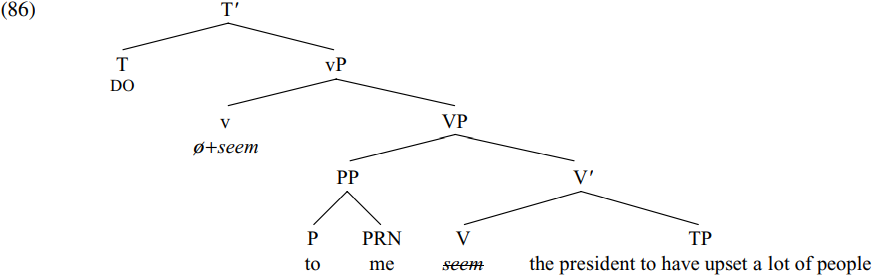

A further possibility to be explored if there are parallels between phases in the clausal and nominal domains is that just as CPs introduced by the prepositional complementizer for are phases, so too prepositional phrases may also be phases. This would provide one way of accounting for the fact that the auxiliary probe do cannot pick out me as its goal in structures such as (86) below:

If PP is a phase, the Phase Impenetrability Condition (1) will mean that the pronoun me is impenetrable to any head outside the PP to me. Consequently, me cannot serve as a goal for do, and the probe do therefore locates the alternative goal the president, agreeing with it, assigning it nominative case and moving it to spec-TP. Merging the resulting TP with a null declarative complementizer derives the structure associated with:

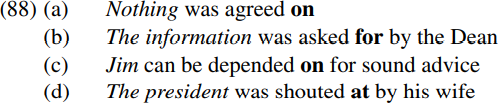

However, one apparent problem posed by the assumption that PPs are phases is how we account for the fact that prepositional complements can be passivized in sentences such as:

In each of the sentences in (88), the italicized nominal seems to originate as the complement of the bold-printed preposition. If prepositional phrases are phases, we would expect the complement of a preposition to be impenetrable to an external head and hence not to be passivisable. To see why, suppose that we arrive at a point in the derivation of (88a) where we have generated the structure shown in simplified form below:

If PP is a phase, the domain of the PP phase (i.e. the nothing complement of the preposition on) will be impenetrable to the external T probe BE, so preventing BE from agreeing with, assigning nominative case to and triggering passivisation of nothing. An analysis along the lines of (89) would therefore wrongly predict that sentences like (88) are ungrammatical. Does the fact that sentences like (88) are grammatical therefore provide us with evidence that PPs are not phases?

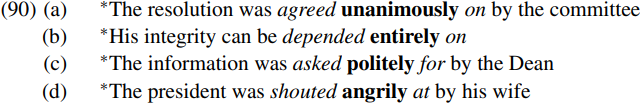

Not necessarily. Radford (1988, pp. 427–32) argues that in prepositional passives like those in (88) above the preposition is adjoined to the verb (forming what pedagogical grammars of English sometimes call a phrasal verb). Part of the evidence in support of such an analysis is that it correctly predicts that no other (bold-printed) constituent can be positioned between the (italicized) verb and preposition in prepositional passives like (90) below:

If prepositional passives do indeed involve a structure in which the preposition is adjoined to the verb, (88a) will have a structure along the lines shown in simplified form in (91) below at the point at which the T probe BE is introduced into the derivation:

The probe [T be] will then agree with, assign nominative case to and trigger passivisation of the pronoun nothing, thereby correctly predicting the grammaticality of (88a). If such an analysis can be maintained, sentences like (88) pose no problem for the hypothesis that PPs are phases.

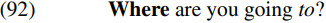

A further empirical challenge to the phasal status of PPs comes from the fact that (in informal styles of English) the complement of a preposition can undergo wh-movement, so stranding the preposition in sentences like:

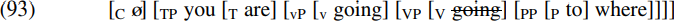

Suppose we follow Chomsky in assuming that intransitive light verbs do not have an [EPP] feature triggering wh-movement, and suppose that we have reached the stage of derivation shown in simplified form in (93) below:

The affixal [TNS] feature of C will attract are to move from T to C. The [WH, EPP] features of C need to attract where to move to spec-CP in order to derive (92).

But if PP is a phase, where will have undergone transfer at the end of the PP phase and so be impenetrable to C (and indeed to any head outside PP). It would therefore seem that we wrongly predict that sentences like (92) are ungrammatical (as indeed their counterparts are in many other languages). Does this provide us with evidence that PPs are not phases?

Once again, not necessarily. After all, a phase head like C can have an [EPP] feature permitting a wh-expression to move into spec-CP, and then be attracted by a higher head. Suppose, therefore, that in colloquial English, a preposition can carry an [EPP] feature. If this is so, the wh-word where can move to spec-PP in (93), so that at the stage when C is introduced into the derivation, we will have the structure (94) below (if we follow Chomsky in assuming that intransitive verb phrases are not phases):

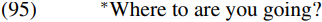

Since the edge of a phase (i.e. its specifier and head) are accessible to a c-commanding probe, and since where is on the edge of PP in (94) by virtue of being its specifier, nothing prevents the C probe from picking out where as its goal, so triggering movement of where to spec-CP. Concomitant movement of the auxiliary are from T to C will derive the structure associated with (92) Where are you going to? If we suppose that the Convergence Principle requires preposing of the smallest accessible wh-constituent in structures like (94) it follows that we correctly predict that only where will be preposed, not the PP where to – so accounting for the ungrammaticality of:

However, in sentence fragments like that produced by speaker B below, we do indeed find structures of the form wh-word+preposition:

Structures like where to? may provide us with some evidence in support of supposing that prepositions can have an [EPP] feature triggering movement of a wh-expression to spec-PP (though it should be noted that structures like (96B) are subject to strong constraints on the choice of wh-word and preposition: see Radford 1993 for some discussion). A final point to note about prepositions with wh-complements is that if we assume that P does not have an [EPP] feature in those languages and language varieties which do not allow preposition stranding (e.g. formal styles of English), we can account for why sentences like (92) are not grammatical in the relevant languages/varieties.

Our discussion has been exploratory in nature, considering the possibility that both transitive and intransitive light verbs may have an [epp] feature which triggers A-bar movement, and that the CP and (transitive) vP phases found in the clausal domain may have analogues in the nominal domain, with DP and/or PP perhaps being phases. As is clear from our discussion, any such claim is far from straightforward, and requires us to make additional assumptions if it is to be workable – e.g. about D having an [EPP] feature in sentences like (83), and P having an [EPP] feature in sentences like (92). Clearly, more research is needed in order to determine whether DPs and/or PPs are indeed phases.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|