Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-11-15

Date: 28-1-2022

Date: 2023-12-01

|

The overall conclusion to be drawn from our discussion so far is that subjects originate internally within VP, as θ -marked arguments of the verb. In all the structures we have looked at until now, the verb phrase has contained both a complement and a specifier (the specifier being the subject of the verb). However, in this and subsequent sections we look at VPs containing a verb and a complement but no specifier, and where it is the complement of the verb which subsequently moves to spec-TP.

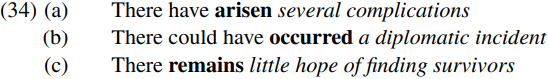

One such type of VP are those headed by a special subclass of intransitive verbs which are known as unaccusative predicates for reasons which will become apparent shortly. In this connection, consider the syntax of the italicized arguments in structures such as the following:

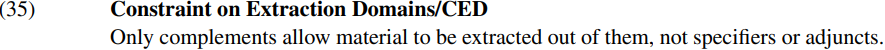

The fact that the italicized expressions are positioned after the bold-printed verbs suggests that they function as the complements of the relevant verbs – and indeed there is syntactic evidence in support of this view. Part of the evidence comes from their behavior in relation to a constraint on movement operations discovered by Huang (1982) which we discussed and characterized as follows:

In the light of Huang’s CED constraint, consider a sentence such as:

In the light of Huang’s CED constraint, consider a sentence such as:

Here, the wh-phrase how many survivors has been extracted (via wh-movement) out of the bracketed expression some hope of finding how many survivors. Given that the Condition on Extraction Domains tells us that only complements allow material to be extracted out of them, it follows that the bracketed expression in (36) must be the complement of the verb remain. By extension, we can assume that the italicized expressions in (34) are likewise the complements of the bold-printed verbs.

Here, the wh-phrase how many survivors has been extracted (via wh-movement) out of the bracketed expression some hope of finding how many survivors. Given that the Condition on Extraction Domains tells us that only complements allow material to be extracted out of them, it follows that the bracketed expression in (36) must be the complement of the verb remain. By extension, we can assume that the italicized expressions in (34) are likewise the complements of the bold-printed verbs.

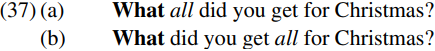

A further argument supporting the claim that unaccusative subjects are initially merged as complements comes from observations about quantifier stranding in the West Ulster variety of English. McCloskey (2000) notes that West Ulster English allows wh-questions such as (37) below which have the interpretation ‘What are all the things that you got for Christmas?’:

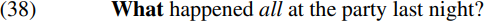

He argues that when the universal quantifier all is used to modify a wh-word like what, wh-movement can either move the whole expression what all to the front of the sentence (as in 37a), or can move the word what on its own, thereby stranding the quantifier in situ (as in 37b). In the light of his observation, consider the following sentence:

The fact that the quantifier all is stranded in a position following the unaccusative verb happened suggests that the wh-expression what all originates in postverbal position as the complement of the verb happened. More generally, sentences like (38) provide empirical evidence in support of positing that unaccusative subjects are initially merged as complements.

However, the unaccusative complements italicized in structures like (34) differ in an important respect from the complements of typical transitive verbs. A typical transitive verb has a thematic subject and a thematic complement, and assigns accusative case to its complement (as in She hit him, where hit has the nominative AGENT subject she and the accusative THEME complement him).

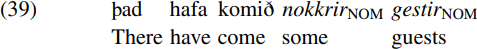

However, unaccusative structures like (34) differ from transitive structures in that they have a non-thematic there subject (which is non-thematic in the sense that it isn’t a thetamarked argument of the verb, but rather is a pure expletive), and (in languages which have a richer case system than English) the italicized complement receives nominative (= NOM) case, as the following Icelandic example (which Matthew Whelpton kindly asked Johannes Gisli J´onsson to provide for me) illustrates:

Because they don’t assign accusative case to their complements, such verbs are known as unaccusative predicates.

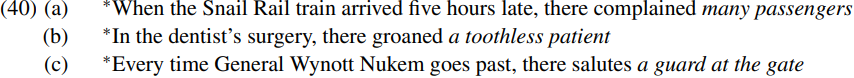

Not all intransitive verbs allow their arguments to be positioned after them, however – as we see from the ungrammaticality of sentences such as (40) below:

Intransitive verbs like complain/groan/salute are known as unergative verbs: they differ from unaccusatives in that the subject of an unergative verb has the thematic role of an AGENT argument, whereas the subject of an unaccusative verb has the thematic property of being a THEME argument.

Intransitive verbs like complain/groan/salute are known as unergative verbs: they differ from unaccusatives in that the subject of an unergative verb has the thematic role of an AGENT argument, whereas the subject of an unaccusative verb has the thematic property of being a THEME argument.

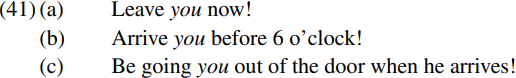

In addition to the contrast illustrated in (34) and (40) above, there are a number of other important syntactic differences between unaccusative verbs and other types of verb (e.g. unergative verbs or transitive verbs). For example, Alison Henry (1995) notes that in one dialect of Belfast English (which she calls dialect A) unaccusative verbs can have (italicized) postverbal subjects in imperative structures like:

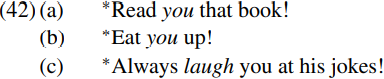

By contrast, other (e.g. unergative or transitive) verbs don’t allow postverbal imperative subjects, so that imperatives such as (42) below are ungrammatical in the relevant dialect:

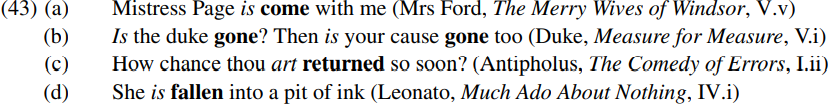

Additional evidence for positing that unaccusative verbs are syntactically distinct from other verbs comes from auxiliary selection facts in relation to earlier stages of English when there were two perfect auxiliaries (have and be), each taking a complement headed by a specific kind of verb. Unaccusative verbs differed from transitive or unergative verbs in being used with the perfect auxiliary be, as the sentences in (43) below (taken from various plays by Shakespeare) illustrate:

We find a similar contrast with the counterparts of perfect have/be in a number of other languages – e.g. Italian and French (cf. Burzio 1986), Sardinian (cf. Jones 1994), German and Dutch (cf. Haegeman 1994), and Danish (cf. Spencer 1991): see Sorace (2000) for further discussion. A last vestige of structures like (43) survives in present-day English structures such as All hope of finding survivors is now gone.

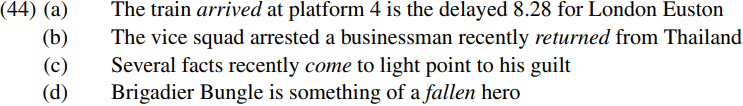

A further difference between unaccusative predicates and others relates to the adjectival use of their perfect-participle forms. As the examples below indicate, perfect-participle (-n/-d) forms of unaccusative verbs can be used adjectivally (to modify a noun), e.g. in sentences such as:

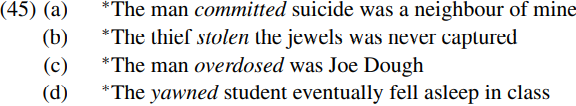

By contrast, perfect-participle forms of (active) transitive verbs or unergative verbs cannot be used in the same way, as we see from the ungrammaticality of examples like (45) below:

In this respect, unaccusative verbs resemble passive participles, which can also be used adjectivally (cf. a changed man, a battered wife, a woman arrested for shoplifting etc.). Additional syntactic differences between unaccusative verbs and others have been reported for other languages (see e.g. Burzio 1986 on ne cliticisation in Italian, and Contreras 1986 on bare nominals in Spanish).

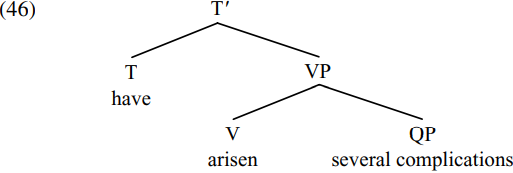

We thus have a considerable body of empirical evidence that unaccusative subjects behave differently from subjects of other (e.g. unergative or transitive) verbs. Why should this be? The answer given in work dating back to Burzio (1986) is that the subjects of unaccusative verbs do not originate as the subjects of their associated verbs at all, but rather as their complements, and that unaccusative structures with postverbal arguments involve leaving the relevant argument in situ in VP-complement position – e.g. in unaccusative expletive structures such as (34) above, and in Belfast English unaccusative imperatives such as (41). This being so, a sentence such as (34a) There have arisen several complications will be derived as follows. The quantifier several merges with the noun complications to form the QP several complications. This is merged as the complement of the unaccusative verb arisen, forming the VP arisen several complications. The resulting VP is merged with the auxiliary have to form the T-bar shown in simplified form below:

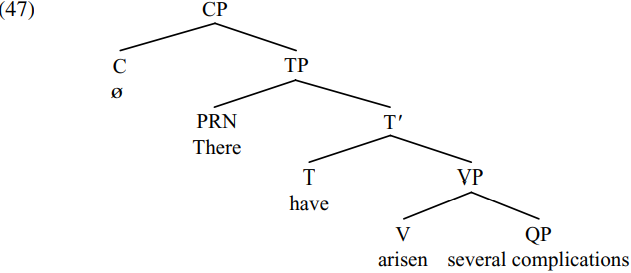

The [EPP] feature carried by the finite T constituent have requires it to have a nominal expression as its specifier. This requirement is satisfied by merging expletive there in spec-TP. The resulting TP there have arisen several complications is then merged with a null declarative-force complementizer to form the CP (47) below:

And (47) is the structure of (34a) There have arisen several complications.

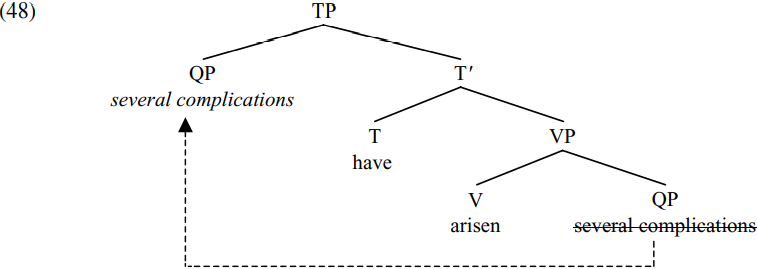

However, an alternative way for the T constituent in (46) to satisfy the [EPP] requirement to have a nominal specifier is for T to attract a nominal to move to spec-TP. In accordance with the Attract Closest Principle, T will attract the closest nominal within the structure containing it. Since the only nominal in (46) is the QP several complications, T therefore attracts this QP to move to spec-TP in the manner shown in simplified form in (48) below:

The type of movement involved is the familiar A-movement operation which moves an argument from a position lower down in a sentence to become the structural subject (and specifier) of TP. The resulting TP in (48) is subsequently merged with a null complementizer marking the declarative force of the sentence, so generating the structure associated with Several complications have arisen.

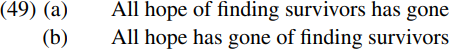

The A-movement analysis of unaccusative subjects outlined in (48) above allows us to provide an interesting account of sentence pairs like that in (49) below:

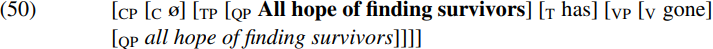

Since go is an unaccusative verb, the QP all hope of finding survivors will originate as the complement of gone. Merging gone with this QP will derive the VP gone all hope of finding survivors. The resulting VP is merged with the T constituent has to form the T-bar has gone all hope of finding survivors. Since T has an [EPP] feature requiring it to project a specifier, the QP all hope of finding survivors is raised to spec-TP, leaving an (italicized) copy behind in the position in which it originated. Merging the resulting TP with a null complementizer marking the declarative force of the sentence derives the structure shown in simplified form in (50) below:

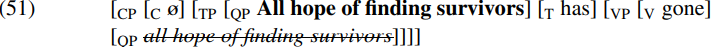

In the case of (49a), the whole of the QP all hope of finding survivors is spelled out in the bold-printed spec-TP position it moves to, and the italicized copy of the moved QP in VP-complement position is deleted in its entirety – as shown in simplified form in (51) below:

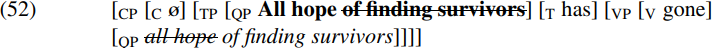

In the case of (49b), the quantifier all and the noun hope are spelled out in the bold-printed position they move to in (50), and the PP of finding survivors is spelled out in the VP-complement position in which it originates – as shown in (52) below:

(52) thus presents us with another example of the discontinuous/split spellout phenomenon. It also provides evidence in support of taking A-movement (like other movement operations) to be a composite operation involving copying and deletion.

|

|

|

|

"إنقاص الوزن".. مشروب تقليدي قد يتفوق على حقن "أوزيمبيك"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الصين تحقق اختراقا بطائرة مسيرة مزودة بالذكاء الاصطناعي

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ووفد من جامعة البصرة يبحثان سبل تعزيز التعاون المشترك

|

|

|