Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-10-06

Date: 2023-11-07

Date: 2023-08-14

|

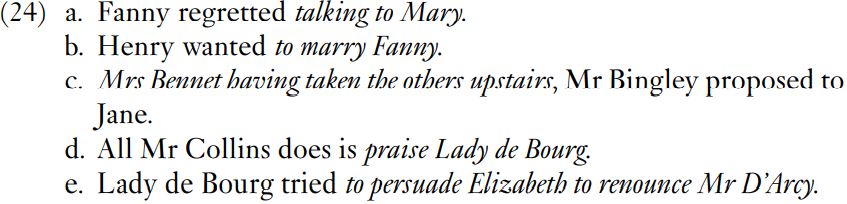

The clauses examined in this chapter all have a finite verb. Much contemporary analysis recognizes a category of non-finite clauses – sequences of words which lack a finite verb but nonetheless are treated as subordinate clauses. Examples are given in (24), with the non-finite clauses in italics.

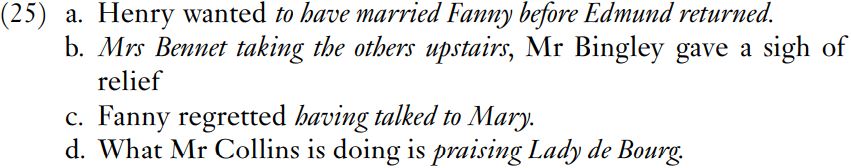

Such sequences were until recently treated as phrases – for instance, to marry Fanny in (24b) was described as an infinitive phrase, and talking to Mary in (24a) as a gerund phrase. There are, however, good reasons for treating them as clauses. Like the classical finite subordinate clauses, they contain a verb and a full set of modifiers – marry in (24b) has Fanny as a complement, talking in (24a) has to Mary as a directional complement, and having taken in (24c) has Mrs Bennet and the others as complements and upstairs as a directional complement. They can have aspect, as shown by (25a, c) which are Perfect and by (25b) which is progressive.

Such sequences were until recently treated as phrases – for instance, to marry Fanny in (24b) was described as an infinitive phrase, and talking to Mary in (24a) as a gerund phrase. There are, however, good reasons for treating them as clauses. Like the classical finite subordinate clauses, they contain a verb and a full set of modifiers – marry in (24b) has Fanny as a complement, talking in (24a) has to Mary as a directional complement, and having taken in (24c) has Mrs Bennet and the others as complements and upstairs as a directional complement. They can have aspect, as shown by (25a, c) which are Perfect and by (25b) which is progressive.

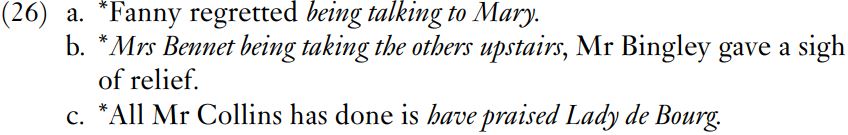

Against the above data must be set the fact that non-finite constructions are highly limited in their grammar. Examples (24a–e) exclude tense and modal verbs such as CAN, MAY, MUST. They exclude interrogative and imperative constructions and do not allow prepositional phrase fronting or negative fronting. In spite of (25), BE is excluded from (24a) and (25b) – see (26a, b). HAVE is excluded from (24d) – see (26c).

Against the above data must be set the fact that non-finite constructions are highly limited in their grammar. Examples (24a–e) exclude tense and modal verbs such as CAN, MAY, MUST. They exclude interrogative and imperative constructions and do not allow prepositional phrase fronting or negative fronting. In spite of (25), BE is excluded from (24a) and (25b) – see (26a, b). HAVE is excluded from (24d) – see (26c).

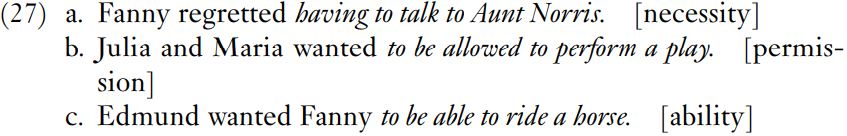

The non-finite constructions do allow some modality to be signaled, that is, events can be presented as necessary, or requiring permission, or requiring ability, as in (27a–c).

The non-finite constructions do allow some modality to be signaled, that is, events can be presented as necessary, or requiring permission, or requiring ability, as in (27a–c).

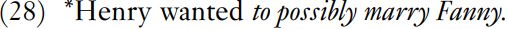

The presentation of an event as possible is excluded, or at least very rare.

The presentation of an event as possible is excluded, or at least very rare.

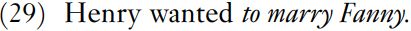

As shown by (12) above, in a given sentence, finite subordinate clauses have their own set of participants independent of the participants in the main clause. This is not true of most non-finite constructions. Consider (29), which brings us to the traditional concept of the understood subject.

The infinitive construction to marry Fanny has no overt subject noun phrase, but Henry is traditionally called the understood subject of marry. That is, traditionally it was recognized that (29) refers to two situations – Henry’s wanting something, and someone’s marrying Fanny. Furthermore, it was recognized that Henry is the person doing the wanting, so to speak, and also the person (in Henry’s mind) marrying Fanny. The syntax is rather condensed relative to the semantic interpretation, since there is only one finite clause but two propositions, one for each situation. In contemporary terms, the notion of understood subject is translated into that of control. The subject of WANT is said to control the subject of the verb in the dependent infinitive. That is, there is a dependency relation between the infinitive and the subject of wanted. Remember that the heads of phrases were described as controlling their modifiers, in the sense of determining how many modifiers could occur and what type. In connection with Henry wanted to marry Fanny, the noun phrase Henry determines the interpretation of another, invisible, noun phrase, the subject of marry. The technical term for this relationship is ‘control’; it is important to note that ‘control’ has these different uses.

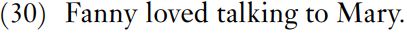

In (30), a similar analysis is applied to the gerund, the -ing phrase that complements loved, where the understood subject of talking is Fanny. In contemporary terms, the subject of LOVE is held to control the subject of the dependent gerund – here, the subject of loved controls the subject of talking to Mary.

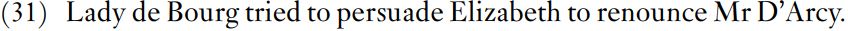

With respect to (31), traditional analysis recognizes one clause but more than one potential situation: Lady de Bourg tried to do something, Lady de Bourg persuade Elizabeth, and Elizabeth renounce Mr D’Arcy. The subject of tried controls the subject of the dependent infinitive, here to persuade. To persuade in turn has a dependent infinitive – to renounce. The object of persuade, Elizabeth, controls the subject of to renounce.

What the above facts boil down to is that on the hierarchy of clauseness, main clauses outrank everything else, and subordinate finite clauses outrank by a good head the candidate non-finite subordinate clauses. Why then do contemporary analysts see the non-finite sequences in (24) as clauses, albeit non-finite? The answer is that they give priority to the fact that non-finite and finite sequences have the same set of complements and adjuncts. Verbs exercise the same control over the types and number of their complements in finite and non-finite constructions; for example, PUT requires to its right a noun phrase and a directional phrase, in both The child put the toy on the table and The child tried to put the toy on the table. Example (24c) has an overt subject, Mrs Bennet, and the other non-finite constructions have understood subjects.

What the above facts boil down to is that on the hierarchy of clauseness, main clauses outrank everything else, and subordinate finite clauses outrank by a good head the candidate non-finite subordinate clauses. Why then do contemporary analysts see the non-finite sequences in (24) as clauses, albeit non-finite? The answer is that they give priority to the fact that non-finite and finite sequences have the same set of complements and adjuncts. Verbs exercise the same control over the types and number of their complements in finite and non-finite constructions; for example, PUT requires to its right a noun phrase and a directional phrase, in both The child put the toy on the table and The child tried to put the toy on the table. Example (24c) has an overt subject, Mrs Bennet, and the other non-finite constructions have understood subjects.

The latter ties in with the important business of semantic interpretation. Finite clauses are held to express propositions, and so are nonfinite clauses, once the understood subject is, so to speak, filled in. (Note that prioritising data, facts, tasks and various theoretical concerns is an integral part of any analytic work. Raw data are dumb until they are interpreted in the light of this or that theory and put to work in a solution to this or that theoretical problem.(

What are called free participles, adjuncts containing -ing forms, pose interesting problems. Consider (32a, b), which are the same construction as exemplified by (24c).

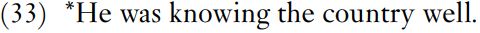

The problem is this. The non-finite constructions in (24) can be straightforwardly correlated with finite clauses, Henry marries Fanny, Fanny talks to Mary, Mrs Bennet had taken the others upstairs and so on. Example (32a) contains knowing, but in spite of this being called a free participle, KNOW does not have -ing forms that combine with BE, as shown by (33).

Slamming the door in (32b) is equally problematic. The free participle sequence cannot be related to When/while he was slamming the door but only to When he had slammed the door. That is, the path from the free participle to the time clause would involve the introduction of a different auxiliary, HAVE. In general, free participles are best treated as a nonfinite type of clause with only a very indirect connection, whatever it might be, with finite clauses.

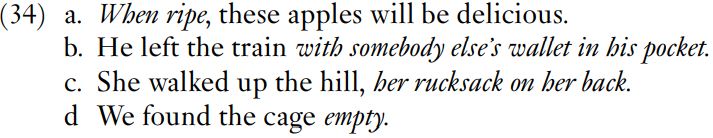

Non-finite constructions with infinitives and participles at least contain a verb form, even if it is non-finite. Some analysts even propose treating the parts in bold in (34) as clauses, although they have no verb form of any kind.

Example (34a) comes closest to a clause, in that the candidate sequence contains when, which looks like a complementizer. Example (34a) could be seen as resulting from ellipsis, the ellipted constituents being a noun phrase and some form of BE: when they are ripe —> when ripe. Examples (34b, c) are unlikely candidates, on the grounds that they cannot be easily correlated with a main clause. It is impossible to insert an -ing form into (34b) *He left the train with somebody else’s wallet being in his pocket: in fact, this construction is used only preceding a main clause and typically in order to present one situation as the cause of another; compare the earlier example With Emma having left Hartfield Mr Woodhouse was unhappy, and With somebody else’s wallet being in his pocket, he was glad not to be stopped by any policemen.

None of the above contradicts the semantic facts that, for example, (34c) and (34d) express several propositions: ‘She walked up the hill’ + ‘She had her rucksack’ + ‘Her rucksack was on her back’ for (34c) and ‘We found the cage’ + ‘The cage was empty’ for (34d). The moral is that while semantic facts should be taken into account, an analysis of syntax should never depend on semantic facts alone. The structures in (34) express propositions but are not even non-finite clauses.

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

سماحة السيد الصافي يؤكد ضرورة تعريف المجتمعات بأهمية مبادئ أهل البيت (عليهم السلام) في إيجاد حلول للمشاكل الاجتماعية

|

|

|