Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-10-21

Date: 2023-09-10

Date: 2023-10-06

|

These criteria have to do with inflectional suffixes, as described above in connection with the tiger examples, and the information signalled by them, and were developed on the basis of languages such as Classical Latin and Classical Greek. We looked at Russian examples above because Russian is not only very like Latin and Greek in its richness of inflectional suffixes but is also a living language. It will be helpful to take a further look at Russian before returning to English.

Examples (1a–c) show that nouns in Russian take different suffixes which signal the relationship between the nouns and the verb in a clause. These relationships are known as case, and nouns are said to be inflected for the category of case. (‘Case’ derives from the Latin word for a fall, casus. The basic form of a noun, such as sobaka in (1a) – the subject form was thought of as upright, and the other forms were thought of as falling away from the subject form.) Other information is signalled by case suffixes in Indo-European languages. Consider (2).

In (2a), sobaki is the subject but also plural, and it has a different suffix, -i. In (2b), sobakam refers to the recipient and is plural and it too has a different suffix from the one in (1c), -am. That is, the case suffixes actually signal information about case and about number.

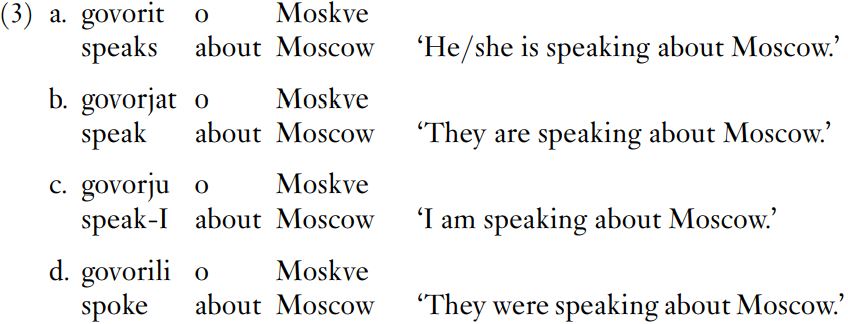

Verbs in Russian signal information about time, person and number, as illustrated in (3).

Examples (3a–d) all refer to an event of speaking about Moscow: (3a) and (3b) place that event in present time; the speaker, as it were, says ‘I am speaking to you now and they are speaking about Moscow’. Example (3d) presents the event in past time; the speaker can be imagined as saying ‘I am speaking to you now and at some before this they were speaking about Moscow’. Information about the time of an event is signalled by the difference in form between govorit and govorjat on the one hand and govorili on the other, the l in govorili indicating past time. Such differences in verbs are said to express tense.

Example (3a) contains govorit, and (3b) contains govorjat. Both are said to be in the third person; in the traditional scheme, first person is the speaker, at the centre of any piece of interaction by means of language; close to the centre is second person, the person(s) addressed by the speaker. Other participants, or other people or things talked about by the speaker, are third persons. The contrasts in form are said to express person. (The term ‘person’ is not entirely appropriate for animals or inanimate objects, but human beings tend to place human beings at the centre of their thinking about the world; typical conversation is taken to be by human beings about human beings.)

Returning to (3a) and (3b), (3a) presents the speaking as being done by one person, (3b) presents it as being done by more than one person. These contrasts are said to express number (as does a different set of contrasts in the shape of nouns, as illustrated in (1) and (2).

In the languages regarded as native to Europe (belonging mostly to the Indo-European and Finno-Ugric families), the words classed as nouns carry information about number and, in some languages, about case; words classed as verbs carry information about tense, person and number (and some other types of information not mentioned here – for a more detailed discussion. In traditional terms, nouns are inflected for case and number, and verbs are inflected for tense, person and number. In some languages, adjectives too are inflected for case and number. Adverbs and prepositions are typically not inflected, though some prepositions in the Celtic languages (Scottish and Irish Gaelic, Welsh and Breton (also Cornish in Cornwall and Manx in the Isle of Man) do have inflected forms as a result of historical change. It is as though in English the sequences to me and to you had coalesced into what were perceived as single words, tme and tyou (the latter probably pronounced chew).

English does not have the rich system of inflections possessed by languages such as Russian, but English nouns do take suffixes expressing number (cat and cats, child and children and so on), and English verbs do take suffixes expressing tense: pull and pulls vs pulled. There are of course nouns, such as mouse–mice, that express number by other means, and there are verbs, such as write–wrote, eat–ate, that express tense by other means. Person is expressed only by the -s suffix added to verbs in the present tense – pulls, writes and so on. Of course, English verbs cannot occur on their own in declarative clauses but require at least one noun phrase, which could consist of just a personal pronoun – I, you, he, she, it, we, they. To the extent that English verbs require a noun phrase, which is often a personal pronoun (in 65 per cent of clauses in spontaneous spoken English), we are entitled to regard person as a category intrinsic to the verb in English. (Non-personal pronouns, that is nouns, are by definition third person.)

English adjectives are not associated with number or case, but many of them take suffixes signalling a greater quantity of some property (for example bigger) or the greatest quantity of some property (for example biggest). These morpho-syntactic properties of English words, signalling information about tense, person and number, are presented in this chapter as relevant to the recognition of different word classes .

|

|

|

|

العمل من المنزل أو المكتب؟.. دراسة تكشف أيهما الأفضل لصحتك

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

عناكب المريخ.. ناسا ترصد ظاهرة غريبة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

استقطاب المرضى الأجانب.. رؤية وخطط مستقبلية للعتبة الحسينية في مجال الصحة داخل العراق

|

|

|