Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-01-30

Date: 2023-10-12

Date: 2023-05-12

|

Tense and aspect are inflectional categories that usually pertain to verbs. Both have to do with time, but in different ways.

Tense refers to the point of time of an event in relation to another point – generally the point at which the speaker is speaking. In present tense the point in time of speaking and of the event spoken about are the same. In past tense the time of the event is before the time of speaking. And in future tense the event time is after the time of speaking. This can be represented schematically as in (13), where S stands for the time of speaking and E for the time of the event:

In English, we mark the past tense using the inflectional suffix -ed on verbs (walked, yawned), but there is no inflectional suffix for future tense. Instead, we use a separate auxiliary verb will to form the future tense (will walk, will scream). The use of a separate word to form a tense is called periphrastic marking. Strictly speaking, periphrastic marking is a matter of syntax rather than morphology. Unlike English, Latin marks both past and future inflectionally, that is, by means of morphology on the verb:

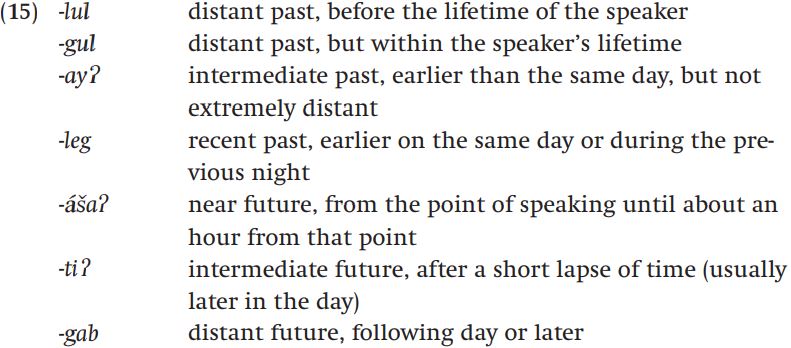

Past, present, and future are not the only possible tenses; some languages distinguish several kinds of past tense and several kinds of future tense, based on how close or distant the event spoken about is from the time of speaking. For example, in the nearly extinct Hokan language Washo, there are four different past tenses and three different future tenses (Mithun 1999: 152–3):

Aspect is another inflectional category that may be marked on verbs. Rather than showing the time of an event with respect to the point of speaking, aspect conveys information about the internal composition of the event or “the way in which the event occurs in time”

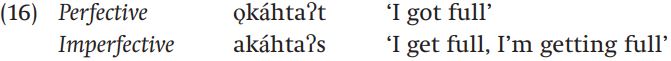

One of the most frequently expressed aspectual distinctions that can be found in the languages of the world is the distinction between perfective and imperfective aspect. With perfective aspect, an event is viewed as completed; we look at the event from the outside, and its internal structure is not relevant. With imperfective aspect, on the other hand, the event is viewed as on-going; we look at the event from the inside, as it were. English isn’t the best language with which to illustrate this distinction, as tense and aspect are not completely distinct from one another, but I can give you a rough example from English. In English, when we say I ate the apple, we not only place the action in the past tense, but also look at it as a completed whole. But if we say I was eating the apple, although the action is still in the past, we focus on the event as it is progressing. The Iroquoian language Seneca has a much clearer distinction between perfective and imperfective aspect (Mithun 1999: 165):

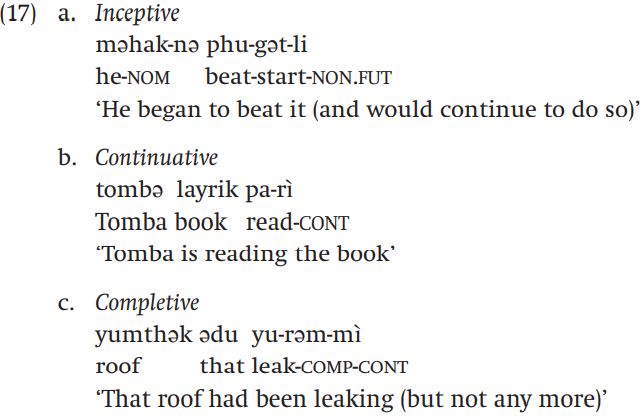

Other forms of aspect focus on particular points in an event. Inceptive aspect focuses on the beginning of an event. Continuative aspect focuses on the middle of the event as it progresses, and completive on the end. We can illustrate these aspects with the following sentences from the Tibeto-Burman language Manipuri (Bhat 1999: 52):

A third category of aspectual distinction can be called quantificational. Quantificational aspectual distinctions concern things like the number of times an action is done or an event happens – once or repeatedly – or how frequently an action is done. Among the quantificational aspects are semelfactive, iterative, and habitual aspects. Actions that are done just once are called semelfactive. The Athapaskan language Koyukon has a special verb stem for actions that are done just once .

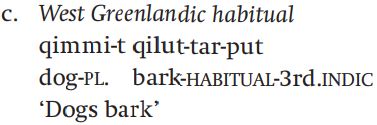

And West Greenlandic has suffixes that express iterative aspect for something that is done repeatedly and habitual aspect for something that is usually or characteristically done (Fortescue 1984: 280–2):

There are other sorts of aspectual distinctions that can be made as well, but these illustrate at least the main types of aspect that can be found in the languages of the world.

English can make some of the aspectual distinctions mentioned above, but it does so periphrastically, using a combination of extra verbs, prepositions, and adverbs to convey such nuances of meaning. In other words, many of these aspectual differences are expressed lexically rather than inflectionally:

Tense and aspect can be and frequently are combined in languages, so for example, it is possible to speak of an event that is on-going in the past or the future. As mentioned above, tense and aspect are often combined in English. The past tense in English is also typically perfective: when we say she walked we generally speak of an event that is conceived of as completed. But when we use the past progressive, as in she was walking, we are talking about something that happened in the past, but which we are thinking of as on-going. The present tense in English can be used to signal the present moment (At this very moment, a dog barks.), or also to convey habitual aspect (Dogs bark.).

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|