Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-10-05

Date: 2023-08-25

Date: 2023-08-29

|

How to: morphological analysis

So far we have looked mostly at English, where you already have a sense of how to divide words into morphemes. But morphologists are, of course, interested in all sorts of languages, and as we progresses, you’ll see that we devote increasing attention to languages that will likely be unfamiliar to you. You should therefore begin to get a sense of how to figure out how the word formation system of another language works.

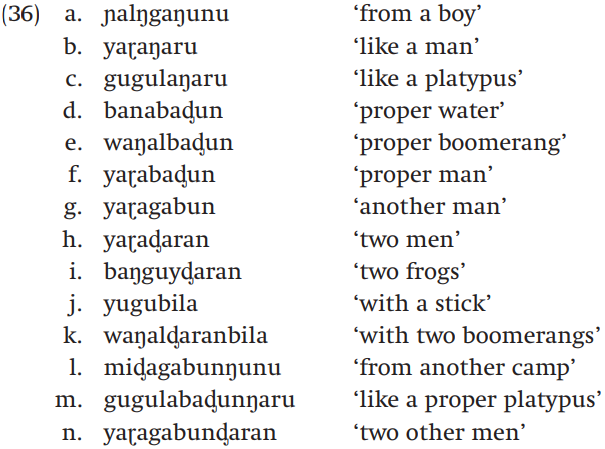

How do linguists go about deciding what words are complex in an unfamiliar language, what sorts of processes are involved in creating complex words, and how to analyze individual words? Consider the words in (36), from the language Dyirbal, a language of the Pama-Nyungan family, formerly spoken in Australia, but now, according to Ethnologue, nearly extinct; data from Dixon (1972: 222–33):

Just by looking at the Dyirbal words (36a) and (36b) and their glosses, you really can’t tell anything. They might be simple or complex, but there’s no way of knowing, because there are no parts of the two words that seem to overlap. But as soon as you look at example (36c) and its gloss, you will notice some overlap with (36b). Both examples share the gloss ‘like a’, and both have some characters at the end that overlap (aŋaru). So you might make a tentative hypothesis that these words are complex, and that they can be broken down into two morphemes, yaɽ+ aŋaru and gugul +aŋaru, respectively. You might also hypothesize that yaɽ means ‘man’, gugul means ‘platypus’, and aŋaru means ‘like a’. This is a good first guess, but you should always be prepared to revise your analysis as you look at more data.

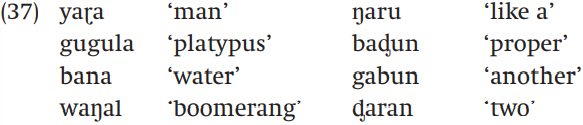

If you then move on and look at examples (36d–f), you’ll notice that they all share part of their meanings (‘proper’), and the end of each word has the sequence baᶁun. It’s therefore reasonable to make the hypothesis that baᶁun means ‘proper’, and that what’s left over means ‘water’ in (36d), ‘boomerang’ in (36e), and ‘man’ in (36f). But now, we need to look back at our analysis of (36b), because our first hypothesis was that yaɽ meant ‘man’, and what’s left over in (36f) is not yaɽ but yaɽa. We therefore need to go back and revise our analysis of examples (36b) and (36c) to be consistent with what we’ve learned from examples (36d–f ). This means that (36b) should be divided into yaɽa+ŋaru and (36c) should be divided into gugula+ŋaru. What we’ve discovered so far is summarized in (37):

We can now build on this hypothesis to analyze some more data. One strategy that’s often good to use is to look for other words in which you already recognize a piece. Indeed it looks like examples (36g) and (36h) both have the piece yaɽa and a gloss that includes ‘man’. If we subtract this piece, we are left with two more bits we can now identify: gabun probably means ‘another’ and ᶁaran ‘two’. This in turn suggests that we can identify the piece baŋguy as meaning ‘frog’.

At this point, we have a good idea how to analyze examples (36b–i), but we still haven’t cracked (36a). Example (36j) is still a problem as well, as so far, it doesn’t overlap with any of the other examples. But as soon as we go on to (36k), we start to get a clue, because there are two morphemes that we can now recognize in this word ‘boomerang’ and ‘two’, leaving only the final bit bila which therefore must mean ‘with’. We can now go back to (36j) and determine that yugu must mean ‘stick’. Example (36l) finally leads us back to example (a): since we can identify a stretch in the middle of (36l) – the morpheme gabun, which we decided means ‘another’– we can guess that miᶁa means ‘camp’ and ŋunu means ‘from’. Why not the opposite, by the way? The reason is that so far it looks like the more semantically contentful morphemes, like ‘man’ and ‘frog’ always come first, and the less contentful come after; we might therefore hypothesize that morphemes like ‘from’ and ‘proper’ are suffixes in Dyirbal. And now we can finally go back to example (36a) and decide that the morpheme for ‘boy’ is ɲalŋga. I leave it to you to analyze the last two examples, and check that our analysis so far is right.

I say ‘so far’ because we have only a tiny bit of data to work with here, and every morphological analysis is provisional on checking it against further data. Sometimes there are loose ends left after we’ve analyzed our data as much as we can. One loose end you might notice in our Dyirbal analysis is that it looks like there is no morpheme in any of our data that corresponds to a word like a in English. It’s impossible to know from this little data set whether Dyirbal has anything that corresponds to indefinite articles .

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|