تاريخ الرياضيات

الاعداد و نظريتها

تاريخ التحليل

تار يخ الجبر

الهندسة و التبلوجي

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

العربية

اليونانية

البابلية

الصينية

المايا

المصرية

الهندية

الرياضيات المتقطعة

المنطق

اسس الرياضيات

فلسفة الرياضيات

مواضيع عامة في المنطق

الجبر

الجبر الخطي

الجبر المجرد

الجبر البولياني

مواضيع عامة في الجبر

الضبابية

نظرية المجموعات

نظرية الزمر

نظرية الحلقات والحقول

نظرية الاعداد

نظرية الفئات

حساب المتجهات

المتتاليات-المتسلسلات

المصفوفات و نظريتها

المثلثات

الهندسة

الهندسة المستوية

الهندسة غير المستوية

مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

التفاضل و التكامل

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

معادلات تفاضلية

معادلات تكاملية

مواضيع عامة في المعادلات

التحليل

التحليل العددي

التحليل العقدي

التحليل الدالي

مواضيع عامة في التحليل

التحليل الحقيقي

التبلوجيا

نظرية الالعاب

الاحتمالات و الاحصاء

نظرية التحكم

بحوث العمليات

نظرية الكم

الشفرات

الرياضيات التطبيقية

نظريات ومبرهنات

علماء الرياضيات

500AD

500-1499

1000to1499

1500to1599

1600to1649

1650to1699

1700to1749

1750to1779

1780to1799

1800to1819

1820to1829

1830to1839

1840to1849

1850to1859

1860to1864

1865to1869

1870to1874

1875to1879

1880to1884

1885to1889

1890to1894

1895to1899

1900to1904

1905to1909

1910to1914

1915to1919

1920to1924

1925to1929

1930to1939

1940to the present

علماء الرياضيات

الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

بحوث و اطاريح جامعية

هل تعلم

طرائق التدريس

الرياضيات العامة

نظرية البيان

SYMBOLIC LOGIC AND THE ALGEBRA OF PROPOSITIONS-Valid arguments

المؤلف:

J. ELDON WHITESITT

المصدر:

BOOLEAN ALGEBRA AND ITS APPLICATIONS

الجزء والصفحة:

61-65

9-1-2017

1789

The central problem in symbolic logic is the investigation of the process of reasoning. In mathematics, as in every deductive science, there are no assertions of "absolute" truth. Rather, a certain set of propositions is assumed without proof, and from this set, other propositions are derived by logical reasoning. For example, when we assert the truth of the Pythagorean theorem, we mean simply that it can be deduced from the axioms of the Euclidean geometry of the plane. It is not true, for instance, for triangles on the surface of a sphere.

We now proceed to investigate those processes which will be accepted as valid in the derivation of a proposition, called the conclusion, from other given propositions, called the premises. We define an argument to be a process by which a conclusion is formed from given premises. An argument is valid if and only if the conjunction of the premises implies the conclusion. That is, the argument which yields a conclusion r from premises p1, P2, ... , pn is valid if and only if the proposition (P1…..P2….. pn) → r is a tautology. In general, there are three ways to check the validity of a given argument. The first is to check it directly from the definition by using a truth table; that is, for the argument above, the truth-table method is used to show that (P1…..P2….. . pn) → r is a tautology. The second method is to show that the proposition (P1…..P2….. . pn) → r can be reduced to 1, using the standard methods of simplification. The third, and often the simplest of the three, is to reduce the argument to a series of arguments each of which is known to be valid as a result of previous checking. Two of the most frequently used valid arguments are the rule of detachment (also called modus ponens) and the law of syllogism. The rule of detachment is given by the form

We will use this schematic arrangement in stating all our arguments. The premise, or premises, will be listed first and the conclusion will follow beneath a horizontal line. Reasons or explanations may be written to the right of each proposition.

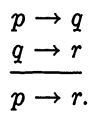

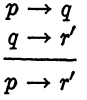

The law of syllogism is given by the form

The validity of this argument, as well as of modus ponens, may be easily checked by either of the first two methods previously mentioned.

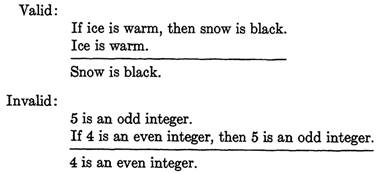

It is important to note that an argument is valid or invalid independently of the truth or falsity of the conclusion. For example, consider the following two arguments. The first is valid although the conclusion is false, and the second is invalid although the conclusion is true.

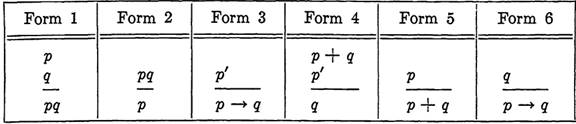

In addition to the rule of modus ponens, and the law of syllogism, the valid argument forms in Table 1-1 have either been checked in previous problems or can readily be verified.

TABLE 1-1

FORMS OF VALID ARGUMENT

In checking the validity of any argument, we will also assume that it is permissible to use either of the following rules of substitution.

RULE 1. Any valid argument which involves a propositional variable will remain valid if every occurrence of a given variable is replaced by a specific proposition.

RULE 2. Any valid argument will remain valid if any occurrence of a proposition is replaced by an equivalent proposition.

From the definition of a valid argument, it follows at once that in addition to any given premises, we may use as a premise any tautology in the algebra of propositions.

In checking a given argument for validity, if it is found or suspected that the argument is invalid, a proof of invalidity can be given more easily than by constructing the entire truth table related to the argument.

It is sufficient to exhibit a particular set of truth values for the propositions involved for which the premises are all true and the conclusion is false. This does nothing more than demonstrate that one row in the truth table, if constructed, would contain a 0 and hence the argument is invalid.

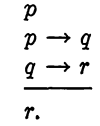

EXAMPLE 1. Show that the following argument is valid:

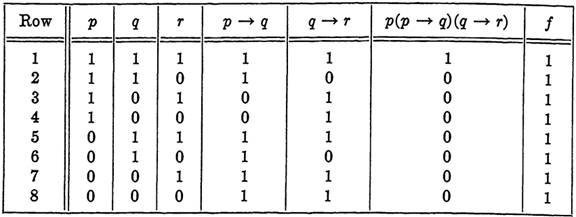

First solution: We construct the truth table for the function

f = [p(p →q)(q →r)] →r.

(See Table 1-2.) Since the f column contains only 1's, the argument is valid.

TABLE 1-2

TRUTH TABLE FOR THE ARGUMENT OF EXAMPLE 1

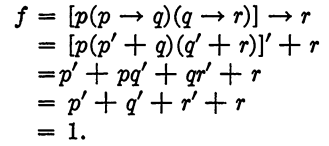

Second solution: Consider the function f as above:

Since f reduces to 1, this also shows that the argument is valid.

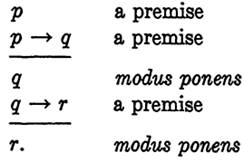

Third solution: Consider the following sequence of arguments:

This sequence of valid arguments shows again, and with less work than either of the first two methods, that the given argument was valid.

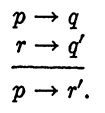

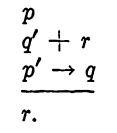

EXAMPLE 2. Cheek the validity of the argument

Solution: The argument

is valid by the law of syllogism. Since r →q' is equivalent to q → r', an application of Substitution Rule 2 completes the proof.

EXAMPLE 3. Show that the following argument is not valid:

Solution: If p is true, q is false, and r is false, then each of the premises is true but the conclusion is false. Hence the argument is invalid.

الاكثر قراءة في الجبر البولياني

الاكثر قراءة في الجبر البولياني

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)