12:52:1

12:52:1  2025-01-15

2025-01-15  1162

1162

Remove the word consequence from your vocabulary entirely and replace it with problem-solving. —Becky, mom blogger and mother of two

Natural consequences are effective teachers. He should learn at age 5 that harsh words tear apart friendships rather than at age 15, and he should learn early that if he doesn’t bring home the books he needs to study for a test, he won’t be able to get them after school closes.

Based on this, most parenting experts suggest that the best response to children who misbehave is consequences. Letting children experience the consequences of their bad choices will teach them to make better choices in the future. Makes sense, right? Not exactly. It only works if the consequence is natural, and the parent had nothing to do with it. Here’s why.

When parents use consequences as discipline, they don’t make them a natural consequence of a child’s actions (I forgot my lunch today, so I was hungry). Consequences to children are threats they hear from their parents’ clenched teeth: “If you have to stop this car and go back again, there will be consequences!” In other words, consequences are just a substitute for punishment. As with all punishments, when we apply consequences, our child becomes defensive, which prevents him from learning the lesson. Even if we don’t invent the consequence out of thin air, our child will see that we can mitigate it and choose not to, and will conclude that we are not on his side, which will make him less cooperative. I’m not suggesting that you turn the heavens and the earth to protect your child from the natural outcome of his choices. We all need to learn lessons, and if your child can do so without significant loss, life is a great teacher. But you need to make sure that these consequences are truly “natural,” so that your child doesn’t see them as punishment and trigger all the negative effects of punishment. Most importantly, make sure your child is convinced that you are not the one who orchestrated these consequences, and that you are by his side until the end, so as not to undermine your relationship with him. Consider the differences in these responses to our child’s request that we bring him the lunch he forgot:

* Response A: (Of course, I will bring your lunch to school, dear. I don’t want you to go hungry, but try to remember it tomorrow). The child may or may not remember his lunch tomorrow. There is no harm in bringing it to him once or twice, if that is easy for you. We have all forgotten things like lunch, and this is not a sign that your child will be irresponsible throughout his life. But it is a sign that you need to help your child with self-regulation strategies.

* Response B: “I certainly will not leave all my work to bring you your lunch. I hope this teaches you a lesson.” The child may learn to remember his lunch. But he concludes that the mother does not care about him, and becomes less cooperative at home. Note that this consequence, although (natural), the mother’s approach has turned it into a punishment.

* Response A: (Okay, I'll bring you your lunch, but it's definitely the last time. You'd forget your head if it wasn't attached to your body, so don't expect me to always drop all my work to save you.) The child doesn't learn to remember his lunch, but he learns that he is a forgetful person who annoys his parents. Then he acts like a forgetful person and an annoyance in the future by forgetting his lunch and expecting his parents to bring it to him.

* Response D: "I'm sorry you forgot your lunch, dear, but it's really inconvenient for me to bring it to you today. I hope you're not starving, I'll have a snack and wait for you to get home and eat together." The child learns to remember his lunch, feels cared for by his mother, and his self-image remains intact.

Does this mean that you should never intervene and help your child draw lessons from the events of her life? Of course not. If you have daily conversations with your child about her life, you will find endless opportunities to ask her questions that prompt her to think and learn. Just remember to focus on resolving the problem rather than assigning blame.

What about situations where we want our child to make amends—when she hurts her sibling, for example? The natural consequence in such a situation is that she has damaged the relationship. If you can give her space to calm down and help her work through the feelings that led her to lash out at her sibling, whoever they are, she will be free to realize the cost of her harsh words and the fact that she loves her sibling, even if he does drive her crazy at times. If you grew up in a family with rituals that encouraged showing appreciation and making amends, and you modeled how to mend fences from an early age, your child will follow suit. It’s okay to express your expectation that family members will make amends if they hurt someone else. Just resist the temptation to force an apology, or it will feel like a lump in your child’s throat. What you want is for your child to feel like she can fix her relationship with her brother, not to feel resentful that you favored him again and have her take the blame.

Reality Of Islam |

|

As air frye

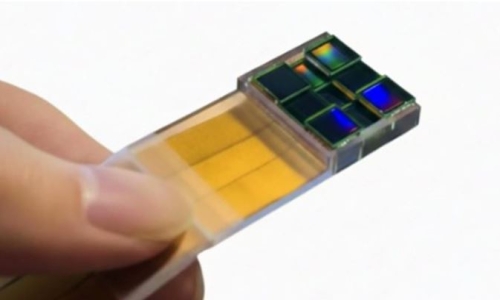

A newly dev

A new lens-

9:3:43

9:3:43

2018-11-05

2018-11-05

10 benefits of Marriage in Islam

7:5:22

7:5:22

2019-04-08

2019-04-08

benefits of reciting surat yunus, hud &

9:45:7

9:45:7

2018-12-24

2018-12-24

advantages & disadvantages of divorce

11:35:12

11:35:12

2018-06-10

2018-06-10

6:0:51

6:0:51

2018-10-16

2018-10-16

8:19:41

8:19:41

2018-06-21

2018-06-21

10:43:56

10:43:56

2022-06-22

2022-06-22

a hero waters thirsty wild animals

9:4:9

9:4:9

2022-01-06

2022-01-06

3:18:29

3:18:29

2022-12-24

2022-12-24

5:57:34

5:57:34

2023-03-18

2023-03-18

2:42:26

2:42:26

2023-02-02

2023-02-02

8:25:12

8:25:12

2022-03-09

2022-03-09

5:41:46

5:41:46

2023-03-18

2023-03-18

| LATEST |