تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

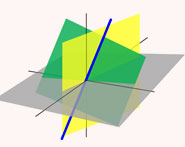

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 29-10-2017

Date: 23-10-2017

Date: 3-11-2017

|

Died: 19 September 1995 in Oakenholt, near Oxford, England

Rudolf Peierls' parents were Heinrich Peierls and Elizabeth Weigert and he was their only child. The family were ethnically Jewish but did not practice the Jewish religion. Heinrich Peierls was director of the Berlin-Oberschöneweide factory of Allgemeine Elektrizitätsgesellschaft when Rudolf was born, and the following year he became a member of the board. When Rudolf was fourteen years old his mother died of Hodgkin's disease, and his father married Else Hermann (who was not Jewish) soon after. Sabine Lee writes [6]:-

From a young age Rudolf was interested in science and engineering. He was a bright child, who found school work easy and was keen to probe further into areas that interested him most: the sciences. His childhood friends remember many an occasion when he would leave their play in order to 'think', only to return once he had solved whatever problem puzzled him at the time.

Peierls wanted to follow a career in engineering but his father doubted that his son had the necessary dexterity and practical skills to excel in this, so he put pressure on Rudolf to enrol in physics courses. He reluctantly took his father's advice and matriculated at Berlin University in 1925 to study experimental physics. Notice that he still wanted to study experimental physics rather than theoretical physics, but practical subjects were in such high demand at Berlin University that the university authorities prevented students taking them in their first year. Peierls was then forced to go down the route he had been trying to avoid and take courses in mathematics and theoretical physics.

The standard way that students in Germany at this time undertook their studies was to move between different universities. After a year at Berlin, Peierls moved to the Department of Theoretical Physics in Munich University in 1926. For two years he studied at Munich where he was particularly influenced by the teaching of Arnold Sommerfeld. It was Sommerfeld who introduced Peierls to quantum mechanics during these two years and this proved highly significant for Peierls' career. It was during this time that he gained a high level of mathematical expertise, following Sommerfeld's philosophy "If you want to be a physicist, you must do three things - first study mathematics, second, study more mathematics, and third, do the same."

Peierls' next move was to the Theoretical Physics Department of Leipzig University in 1928, mainly as a result of Sommerfeld leaving Munich for a world tour. He chose Leipzig because Werner Heisenberg had been appointed as professor there in 1927. He followed Heisenberg's advice of research topic and began the work which would lead to his first paper Zur Theorie der galvanomagnetischen Effekte (1929). In the spring of 1929 Heisenberg also went off on a world tour so Peierls moved university again, this time going to the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule in Zürich to work with Wolfgang Pauli. He now worked on the thermal conductivity in crystals and by the summer of 1929 had achieved sufficient depth of results that he was able to write two papers and to submit a doctoral dissertation to Leipzig University. He was awarded his doctorate from Leipzig in 1929, then in the autumn of that year he was appointed as Pauli's assistant in Zürich.

At Zürich, Peierls worked with Lev Landau who was visiting Zürich. In the summer of 1930 Peierls went to a conference in Odessa where he met not only with Lev Landau, but also many of his colleagues. One of these colleagues was Eugenia Nilolaevna Kannegisser, known as Genia [6]:-

With their German and Russian backgrounds, neither of them could converse in the other's mother tongue and the only common language spoken sufficiently well by both to communicate reasonably comfortably was English. After six months of intense correspondence by letter, Rudolf Peierls travelled to Leningrad again in March 1931, and during his brief stay - much to the dismay of his surprised family - married Genia.

Genia and Rudolf married on 15 March 1931; they had three daughters Joanna, Gaby and Catherine, and one son Ronald who became a computational mathematician.

Peierls was awarded a Rockefeller Fellowship and he spent the first half of the year 1932-33 in Rome with Enrico Fermi, and the second half in England where he worked at Cambridge with Paul Dirac and Ralph Fowler. He turned down an offer of an assistantship at Hamburg despite its high reputation since he saw the problems of rising support for the Nazi party. He was glad, therefore, to accept a position at Manchester. He spent a highly productive year there, working with Hans Bethe, and began publishing papers on nuclear physics in addition to his continuing work on the electron theory of metals. His next position was a two year fellowship held at Cambridge, following which, in 1937, he accepted a professorship in mathematical physics at Birmingham University.

The deteriorating political situation in Germany led to Peierls attempting to gain British citizenship in May 1938 and, at the same time, he tried to reject his German citizenship. This process took time and when World War II began the process was still not complete and Peierls and his wife were both classified as enemy aliens. Restrictions were lifted in February 1940 when his application for British citizenship was approved. However, undertaking war work was still difficult and this would prove particularly so when, together with Otto Frisch (an Austrian), he made it known to the British government through the 3-page Frisch-Peierls memorandum that he had the theoretical knowledge to make an atomic bomb from uranium-235 a possibility. The government set up the MAUD committee to examine the Frisch-Peierls memorandum and at first, because of Peierls and Frisch's German and Austrian backgrounds, they were prevented from taking part. Soon, however, the realisation that it was impossible to prevent the two scientists who had proposed the idea from knowing about it came home to the committee and Peierls and Frisch were invited as members of a technical subcommittee.

Early in 1941 Peierls invited Klaus Fuchs to join him, Otto Frisch and James Chadwick, in the work on the theoretical side of the British project to develop an atomic bomb. In August 1943 the Quebec Conference set up a formal collaboration between Britain and the United States on nuclear weapons research and, after a fact finding mission by Peierls in Washington, all the key British researchers joined the Manhattan Project. Peierls worked first in New York then at Los Alamos until the end of World War II, when he returned to Birmingham. He continued to work there despite offers from Oxford, Manchester, London and Cambridge. During these years, he also worked as a consultant to the British atomic programme at Harwell where Klaus Fuchs, who had worked closely with him on the atomic bomb project, now held a senior position. When Fuchs was exposed as a Russian spy in 1950 it caused considerable embarrassment to Peierls who had to endure press speculation that he was also a spy. The Spectator alleged he spied for the Soviet Union with the codename "perls", but this was totally unfounded [6]:-

His contacts with left-wing colleagues, his friendship with people of Communist persuasion, his marriage to a Russian, his close friendship with Klaus Fuchs - all led to his being viewed with a degree of suspicion by many.

His applications for a visa to visit the United States met with long delays. In 1957 the Americans asked the British to revoke his security clearance, which they did. As a result Peierls resigned from his consultancy role at Harwell.

In 1961 he was offered the Wykeham Chair of Physics at Oxford. By now he was feeling that he had been in Birmingham long enough and was looking for a challenge. However, he did not rush to accept which he did not do until the following year, only taking up the position in 1963. He worked in Oxford until he retired in 1974, then spent the period between February and May of each of the next three years at the University of Washington. The list of other places he visited in the years following his retirement is too long to give here.

Peierls received many honours such as election to the Royal Society in 1945, and receiving their Royal Medal in 1959. He was also awarded the Max Planck Medal (1963), the Enrico Fermi Award (1980), the Matteucci Medal (1982), and the Copley Medal (1986). For his wartime contributions he was made a Commander of the British Empire in 1946, but the most pleasing honour of all was a Knighthood in 1968 since it gave him an acceptance by the British establishment after many years of unfair suspicion.

In 1997, two years after his death, Selected scientific papers of Sir Rudolf Peierls was published. H S Green writes in a review:-

Sir Rudolf Peierls was probably the most influential of the German mathematical physicists who migrated and settled in Britain during the Nazi era. An inveterate traveller, he was well acquainted with nearly all the distinguished mathematical and theoretical physicists of his time and worked with many of them; he also had many young friends and research students who achieved distinction. ... This valuable book features a selection of 72 of the much larger number of scientific papers and lectures that Peierls contributed to the scientific literature, and includes translations into English of his early work as well as personal comments by the author which modestly evaluate the importance of most of the papers. ... Peierls was a highly competent, though not a notably creative mathematician; his principal interest was clearly in making calculations which would lead to a deep understanding of physical phenomena, and he was adept at finding approximations which gave trustworthy numerical results. His more mathematically elegant papers, such as [one] with Dirac and Pryce, were in collaboration with people with more mathematical inclinations. However, it is remarkable how many of these papers have played a crucial role for the subsequent development of their subjects ...

We end this biography by looking briefly at his two books Surprises in theoretical physics (1979) and More surprises in theoretical physics (1991). Describing the first, P Roman writes:-

This unusual, fascinating, slim volume renders exactly what its distinguished author promises: "to illustrate and to entertain"---and to delight the reader, I would like to add. It is based on (obviously leisurely) lectures that Sir Rudolf gave in 1977/78, both in the U.S. and in France. It "presents a number of examples in which a plausible explanation is not borne out by a more careful analysis". Thus the book is didactic and it challenges the reader's intellect. The topics covered are mostly from quantum theory and its applications; statistical physics and even relativity are touched upon. ... The book should be not only a bedside companion for mature scientists but also a challenging, easily followed and highly appreciated "supplementary text" for graduate students in theoretical physics (in Europe, also for advanced undergraduates).

The second text was reviewed by A Ventura who writes:-

Surprises in theoretical physics are either theoretical results in disagreement with naïve physical intuition, or simple solutions to apparently unmanageable problems. A first collection of surprises was published in 1979 and is now supplemented by the present work, with topics taken mainly from the long multifaceted experience of the author. ... this book can be warmly recommended to physics students and to their teachers as a valid auxiliary tool for courses in quantum mechanics, structure of matter and statistical physics.

Another two significant books were The Laws of Nature (1955) and his autobiography Bird of Passage (1985).

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي للقرآن الكريم يقيم جلسة حوارية لطلبة جامعة الكوفة

|

|

|