Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-08-10

Date: 2023-07-15

Date: 2023-04-04

|

The important paper by Katz and Fodor, ‘The Structure of Semantic Theory’ (1963) represented the first attempt to make semantics a systematic part of a linguistic description. (Katz’ paper in this volume is essentially a restatement of this position.) This move provided the impetus for a number of significant changes in syntax as semantic requirements were imposed on the syntactic component. Initially, Katz and Fodor argued that linguistic knowledge could be separated from the rest of a speaker’s knowledge about the world and that the syntactic machinery of GT-1 could provide a basis for a semantic component which would assign a semantic interpretation consisting of one or more readings to each sentence and in addition, would mark those strings which had no readings as semantically anomalous. The lower bound of a semantic theory is determined by examining those abilities or capacities which all fluent speakers of a language share and which cannot be accounted for by the syntactic component alone. Given a situation where a speaker is exposed to a sentence (S) in isolation we may ask what conclusions he is able to come to about S that would not be available to him had he only a syntactic description of S.

This procedure is based on the assumption that ‘ Synchronic linguistic description minus semantics equals grammar’. In general speakers can:

(1) detect non-syntactic ambiguities and characterize the content of each reading of a sentence. If S is the English sentence The bill is large, it will be seen that two meanings are possible although only one structural description is available.

(2) determine the number of readings a sentence has by exploiting semantic relations in the sentence to eliminate potential ambiguities. If S is The bill is large but need not be paid, one of the readings under (1) is eliminated.

(3) detect anomalous sentences such as The paint is silent.

(4) paraphrase sentences by stating for a given S, which other S’s have the same meaning.

In this article only (2) and (3) above are given any serious attention.

The upper bound of a semantic theory is determined by the following argument which is reminiscent of many earlier comments on the impossibility of including meaning, as broadly defined, in linguistics:

Since a complete theory of setting selection must represent as part of the setting of an utterance any and every feature of the world which speakers need in order to determine the preferred reading of that utterance, and since, as we have just seen, practically any item of information about the world is essential to some disambiguation, two conclusions follow. First, such a theory cannot in principle distinguish between the speaker’s knowledge of his language and his knowledge of the world, because, according to such a theory, part of the characterization of a linguistic ability is representation of virtually all knowledge about the world that speakers share. Second, since there is no serious possibility of systematizing all the knowledge of the world that speakers share, and since theory of the kind we have been discussing requires such a systematization, it is ipso facto not a serious model for semantics. However, none of these considerations is intended to rule out the possibility that, by placing relatively strong limitations on the information about the world that a theory can represent in the characterization of a setting, a limited theory of selection by sociophysical setting can be constructed. What these considerations do show is that a complete theory of this kind is impossible. (Katz and Fodor, 1963, p. 179)

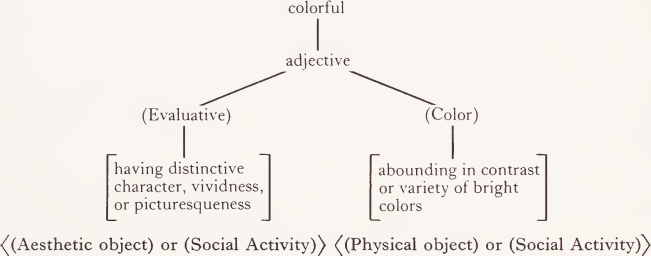

This attempt to present a principled basis for the definition of linguistic meaning is obviously crucial to the incorporation of semantics into grammar. It represents a cautious expansion of the domain of linguistic theories which regards and treats semantics as a completely secondary and subservient component of grammars. In operation, the semantic component takes as input a structural description of some sentence (S). It has available a dictionary entry for each word in S which states not only the syntactic classification of the word but also provides by the use of semantic markers, distinguishers and selection restrictions the information necessary for the operation of the projection rules which combine the meanings of individual words into the meanings possible for the whole sentence. For example, the dictionary entry for colorful will include, according to Katz and Fodor:

Where markers are enclosed in ( ), distinguishers in [ ] and selection restrictions in ( ). The projection rules, beginning at the bottom of a labeled tree, proceed to amalgamate elements at each higher level until the full sentence has received a semantic interpretation. Should any pair of elements violate the selectional restrictions, their combination will be blocked, e.g. colorful void is not possible since void will not contain any of the markers listed above for colorful whereas colorful ball will have four possible readings which combine the two readings for each item.

Two general types of projection rules are discussed. Type 1 rules operate on the kernel sentences produced by phrase structure rules and obligatory transformations. Type 2 rules assign semantic interpretations to more complex sentences formed using optional transformations. Their comments on this issue anticipate the next major change in the syntactic component:

The basic theoretical question that remains open here is just what proper subsets of the set of sentences are semantically interpreted using type 1 projection rules only. One striking fact about transformations is that a great many of them (perhaps all) produce sentences that are identical in meaning with the sentence(s) out of which the transform was built. In such cases, the semantic interpretation of the transformationally constructed sentence must be identical to the semantic interpretation(s) of the source sentence(s), at least with respect to the readings assigned at the sentence level. . .It would be theoretically most satisfying if we could take the position that transformations never change meaning. But this generalization is contradicted by the question transformations, the imperative transformation, the negation transformation, and others. Such troublesome cases may be troublesome only because we now formulate these transformations inadequately, or they may represent a real departure from the generalization that meaning is invariant under grammatical transformations. Until we can determine whether any transformations change meaning, and if some do, which do and which do not, we shall not know what sentences should be semantically interpreted with type 2 projection rules and how to formulate such rules. (Katz and Fodor, 1963, p. 206)

Katz and Postal (1964) offer the assumption that singulary transformations do not change meaning. The ‘ troublesome cases ’ noted above are handled by proposing that the phrase structure rules be permitted to generate items such as I (imperative), Neg (negative), and Q (question) which provide the conditions for the proper application of the relevant transformations. Rather than converting a string such as Boys chase girls into the question Do hoys chase girls? with a consequent shift of meaning due to the transformation, each of the strings will now have a different underlying structure with Q appearing in the second. The next major step (described in Chomsky, 1966) was to allow phrase structure rules to be of the form A-> Sentence which has the effect of eliminating generalized transformations entirely as the phrase structure (or ‘ base ’) component of the grammar now generates a generalized phrase marker which states the relationship among all of the simpler sentences which are sources for the final complex sentence.

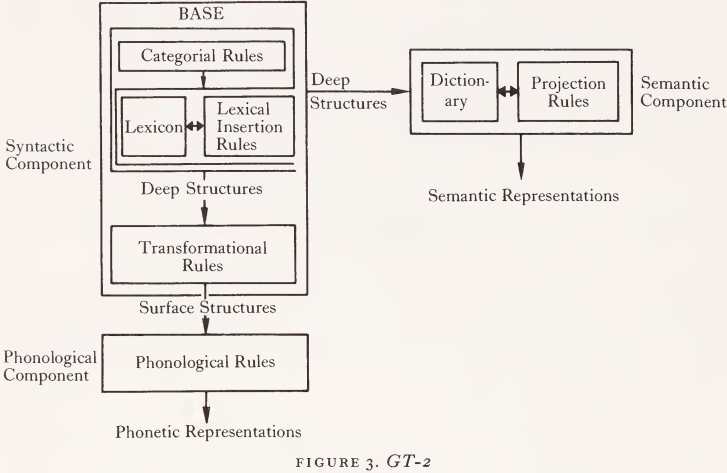

It will be remembered that the phrase structure component of a GT-1 grammar introduced lexical items as lists following some element such as N or V. Given the hierarchical arrangement of words and phrases required by this component, the statement of selectionai restrictions across words and phrases is extremely clumsy. Thus, we can exclude such ungrammatical sentences as *The hoy chase the dog only by setting up nouns which are either singular or plural. But nouns also may be animate or inanimate (i.e. *The rock hated the dog) independently of whether they are singular or plural. Chomsky (1965) suggests that an enormous simplification of the phrase structure component can be achieved by following the model of phonological and semantic analysis and describing each lexical item as a set of features. The syntactic component of a grammar (Figure 3) now consists of two major parts: a base component which generates deep structures and a transformational component which converts deep structures into surface structures. Deep structures provide the input to the interpretive semantic component while surface structures are the input to the interpretive phonological component. The base is further analyzed into a categorial component and a lexicon. The former consists of a set of ordered rewriting rules which provide the recursive power of the grammar and generate trees whose terminal elements consist of grammatical morphemes and empty categories (Δ). The lexicon consists of an unordered set of lexical entries each composed of a set of features. Lexical features are of three kinds: (1) Category features merely indicate the general category to which a lexical item must belong if it is to replace some Δ . Thus, an item with the feature [ + N] may be inserted only in a Δ dominated by N as indicated by the presence of a rule of the form N-> Δ.

(2) Strict subcategorization features refer to the categorical environment in which a lexical item may occur, as defined by such terms from the categorial component as NP (noun phrase), VP (verb phrase), PP (prepositional phrase), etc. Thus, an item with the category feature [ + V] and the strict subcategorization feature [+ -NP] can replace a Δ dominated by V and may occur only in environments which include an immediately following NP. (In more familiar terms, the item is a transitive verb.)

(3) Selectional features refer to the lexical environment in which an item may occur. In particular to those lexical items with which the item in question has a grammatical relation. If an item is marked with the features [ + V] and [+ -NP] as above it may also have the selectional feature [ + animate] Obj which indicates that it takes only animate objects. The content of selectional features is provided by features such as animate or human which apply to nouns.

The following drastically oversimplified example will illustrate the operations of the syntactic component of a GT-2 grammar.

|

|

|

|

"إنقاص الوزن".. مشروب تقليدي قد يتفوق على حقن "أوزيمبيك"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الصين تحقق اختراقا بطائرة مسيرة مزودة بالذكاء الاصطناعي

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتب السيد السيستاني يعزي أهالي الأحساء بوفاة العلامة الشيخ جواد الدندن

|

|

|