تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

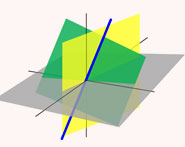

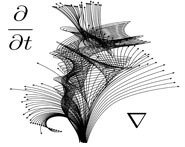

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 20-10-2015

Date: 20-10-2015

Date: 18-10-2015

|

Born: about 60 in Gerasa, Roman Syria (now Jarash, Jordan)

Died: about 120

Nicomachus of Gerasa is mentioned in a small number of sources and we can date him fairly accurately from the information given. Nicomachus himself refers to Thrasyllus who died in 36 AD so this gives lower limits on his dates. On the other hand Apuleius, the Platonic philosopher, rhetorician and author whose dates are 124 AD to about 175 AD, translated Nicomachus's Introduction to Arithmetic into Latin so this gives an upper limit on his dates. One of the most interesting references is by Lucian, the rhetorician, pamphleteer and satirist who was born about 120 AD, who makes one of his characters say:-

Nicomachus of Gerasa is mentioned in a small number of sources and we can date him fairly accurately from the information given. Nicomachus himself refers to Thrasyllus who died in 36 AD so this gives lower limits on his dates. On the other hand Apuleius, the Platonic philosopher, rhetorician and author whose dates are 124 AD to about 175 AD, translated Nicomachus's Introduction to Arithmetic into Latin so this gives an upper limit on his dates. One of the most interesting references is by Lucian, the rhetorician, pamphleteer and satirist who was born about 120 AD, who makes one of his characters say:-

You calculate like Nicomachus.

Clearly Nicomachus had achieved fame for his arithmetical work!

In the paper [7] Dillon argues that Nicomachus died in 196 AD. His argument is based on the fact that Marinus claimed that Proclus believed that he was the reincarnation of Nicomachus. Since Proclus was born in 412 AD and there was a belief among Pythagoreans that reincarnations occurred with an interval of 216 years, the date fits. Although 196 AD is not ruled out by his translator dying in 175 AD (although it comes close) the most serious objection to Dillon's theory seems to be the lack of evidence that Proclus himself believed in the 216 year interval.

Let us move from conjectures to more certain ground, and record that Nicomachus was a Pythagorean. This is obvious from his writings on numbers and music, but we are also told this by Porphyry who says that he was one of the leading members of the Pythagorean School.

Nicomachus wrote Arithmetike eisagoge (Introduction to Arithmetic) which was the first work to treat arithmetic as a separate topic from geometry. Unlike Euclid, Nicomachus gave no abstract proofs of his theorems, merely stating theorems and illustrating them with numerical examples.

However Introduction to Arithmetic does contain quite elementary errors which show that Nicomachus chose not to give proofs of his results because he did not in general have such proofs. Many of the results were known by Nicomachus to be true since they appeared with proofs in Euclid, although in a geometrical formulation. Sometimes Nicomachus stated a result which is simply false and then illustrated it with an example which happens to have the properties described in the result. We must deduce from this that some of the results are merely guesses based on the evidence of the numerical examples (and in some cases perhaps even based on one example!).

An example of this we look more closely at the results which Nicomachus quotes on perfect numbers. He states that the nth perfect number has n digits, and that all perfect numbers end in 6 and 8 alternately. These statements must be merely false deductions from the fact that there were four perfect numbers known to Nicomachus, namely 6, 28, 496 and 8128.

The work contains the first multiplication table in a Greek text. It is also remarkable in that it contains Arabic numerals, not Greek ones. However, in many respects the book is old fashioned in its style since it appears more in tune with the number theoretic ideas of Pythagoras with his mystical approach, rather than a true mathematical approach. To illustrate Nicomachus's rather strange approach to numbers, giving the moral properties, we look at his description of abundant numbers and deficient numbers. An abundant number has the sum of its proper divisors greater than the number, while a deficient number has the sum of its proper divisors less than the number. Nicomachus writes of these numbers in Introduction to Arithmetic (see [6], or [3] for a different translation):-

In the case of the too much, is produced excess, superfluity, exaggerations and abuse; in the case of too little, is produced wanting, defaults, privations and insufficiencies. And in the case of those that are found between the too much and the too little, that is in equality, is produced virtue, just measure, propriety, beauty and things of that sort - of which the most exemplary form is that type of number which is called perfect.

He then continues his description of abundant numbers as resembling an animal:-

... with ten mouths, or nine lips, and provided with three lines of teeth; or with a hundred arms, or having too many fingers on one of its hands....

while a deficient number is like an animal:-

... with a single eye, ... one armed or one of his hands has less than five fingers, or if he does not have a tongue...

For over 1000 years Introduction to Arithmetic was the standard arithmetic text. In view of the comments we have made regarding the work, this may seem a surprising fact. Mathematicians disliked the work, in particular Pappus is said to have despised it. However, several people including Boethius translatedIntroduction to Arithmetic into Latin and it was used as a school book. How then could a poor book become so popular. Heath tries to explain the apparent contradiction in [4], suggesting that:-

... it was at first read by philosophers rather than mathematicians, and afterwards became generally popular at a time when there were no mathematicians left, but only philosophers who incidentally took an interest in mathematics.

Arab translations of Nicomachus's Introduction to Arithmetic were important and in [5] Brentjes studies the influence of these Arabic translations. She concludes that most Arabic texts on number theory written by mathematicians were influenced by both Euclid and Nicomachus, but were mainly influenced by Euclid. However, texts by non-mathematicians were most strongly influenced by Nicomachus. This research in [5] tends to support the views of Heath on this subject.

Nicomachus also wrote two volumes Theologoumena arithmetikes (The Theology of Numbers) which was completely concerned with mystic properties of numbers. However Heath writes [4]:-

The curious farrago which has come down to us under that title and which was edited by Ast [published in Leipzig in 1817] is, however, certainly not by Nicomachus; for among the authors from whom it gives extracts is Anatolius, Bishop of Laodicaea (270 AD); but it contains quotations from Nicomachus which appear to come from the genuine work.

Another work by Nicomachus which has survived is Manual of Harmonics which is a work on music. Again Nicomachus shows the influence of Pythagoras but also Aristotle's theories of music. The work looks at musical notes and the octave. The principles of tuning a stretched string are studied as is an extension of the octave to the two-octave range.

The influences of Pythagoras's theory of music are seen from Nicomachus' (see [1]):-

... assignment of number and numerical ratios to notes and intervals, his recognition of the indivisibility of the octave and the whole tone... But, unlike Euclid, who attempts to prove musical propositions through mathematical theorems, Nicomachus seeks to show their validity by measurement of the lengths of strings.

Both Porphyry and Iamblichus wrote biographies of Pythagoras which quote from Nicomachus. From this evidence some historians have conjectured that Nicomachus also wrote a biography of Pythagoras and, although there is no direct evidence, it is indeed quite possible.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي للقرآن الكريم يقيم جلسة حوارية لطلبة جامعة الكوفة

|

|

|