Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-06-05

Date: 2023-06-16

Date: 21-1-2022

|

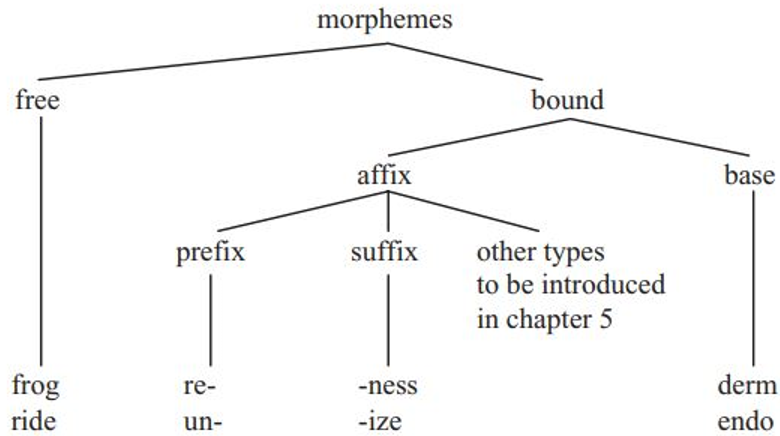

Kinds of morphemes

Most native speakers of English will recognize that words like unwipe, head bracelet or MacDonaldization are made up of several meaningful pieces, and will be able to split them into those pieces:

un / wipe

head / bracelet

McDonald / ize / ation

these pieces are called morphemes, the minimal meaningful units that are used to form words. Some of the morphemes can stand alone as words: wipe, head, bracelet, McDonald. These are called free morphemes. The morphemes that cannot stand alone are called bound morphemes. In the examples above, the bound morphemes are un-, -ize, and -ation. Bound morphemes come in different varieties. Those are prefixes and suffixes; the former are bound morphemes that come before the base of the word, and the latter bound morphemes that come after the base. Together, prefixes and suffixes can be grouped together as affixes.

New lexemes that are formed with prefixes and suffixes on a base are often referred to as derived words, and the process by which they are formed as derivation. The base is the semantic core of the word to which the prefixes and suffixes attach. For example, wipe is the base of unwipe, and McDonald is the base of McDonaldization. Frequently, the base is a free morpheme, as it is in these two cases.

But stop a minute and consider the data in the next Challenge box.

Challenge Divide the following words into morphemes:

• pathology

•psychopath

•dermatitis

•endoderm

Chances are that you recognize that there are two morphemes in each word. However, neither part is a free morpheme. Do we want to call these morphemes prefixes and suffixes? Would this seem odd to you?

If you said that it would be odd to consider the morphemes in our Challenge as prefixes and suffixes, you probably did so because this would imply that words like pathology and psychopath are made up of nothing but affixes!

Morphologists therefore make a distinction between affixes and bound bases. Bound bases are morphemes that cannot stand alone as words, but are not prefixes or suffixes. Sometimes, as is the case with the morphemes path or derm, they can occur either before or after another bound base: path precedes the base ology, but follows the base psych(o); derm precedes another base in dermatitis but follows one in endoderm. This suggests that path and derm are not prefixes or suffixes: there is no such thing as an affix which sometimes precedes its base and sometimes follows it. But not all bound bases are as free in their placement as path; for example, psych(o) and ology seem to have more fixed positions, the former usually preceding another bound base, the latter following. Similarly, the base -itis always follows, and endo- always precedes another base. Why not call them respectively a prefix and a suffix, then?

One reason is that all of these morphemes seem in an intuitive way to have far more substantial meanings than the average affix does. Whereas a prefix like un- (unhappy, unwise) simply means ‘not’ and a suffix -ish (reddish, warmish) means ‘sort of’, psych(o) means ‘having to do with the mind’, -ology means ‘the study of ’, path means ‘sickness’, derm means ‘skin’ and -itis means ‘disease’. Semantically, bound bases can form the core of a word, just as free morphemes can

This figure summarizes types of morphemes.

Another reason to believe that bound bases are different from prefixes and suffixes is that prefixes and suffixes tend to occur more freely than bound bases do. For example, any number of adjectives can be made negative by using the prefix un-, but there are far fewer words with the bound base psych(o). This is perhaps not the best way of distinguishing between bound bases and affixes, though, as there are a few bound bases – -ology is one of them – that occur with great freedom, and there are some prefixes and suffixes that don’t occur all that often (e.g. the -th in width or health). So we’ll stick with the criterion of ‘semantic robustness’ for now. We’ll return in the next chapter to the question of how freely various morphemes are used in word formation.

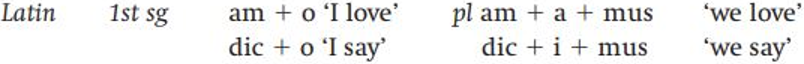

With regard to bases, another distinction that’s sometimes useful in analyzing languages other than English is the distinction between root and stem. In languages with more inflection than English, there is often no such thing as a free base: all words need some sort of inflectional ending before they can be used. Or to put it differently, all bases are bound. Consider the data below from Latin:

In the singular, an ending signaling the first person (“I”) can sometimes attach to the smallest bound base meaning ‘love’ or ‘say’; this morpheme is the root. In the first person plural, and in most other persons and numbers, however, another morpheme must be added before the inflection goes on. This morpheme (an a for the verb ‘love’ and an i for the verb ‘say’) doesn’t mean anything, but still must be added before the inflectional ending can be attached. The root plus this extra morpheme is the stem. Thought of another way, the stem is usually the base that is left when the inflectional endings are removed. We will look further at roots and stems, when we discuss inflection more fully.

|

|

|

|

لخفض ضغط الدم.. دراسة تحدد "تمارين مهمة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

طال انتظارها.. ميزة جديدة من "واتساب" تعزز الخصوصية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مشاتل الكفيل تزيّن مجمّع أبي الفضل العبّاس (عليه السلام) بالورد استعدادًا لحفل التخرج المركزي

|

|

|