النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 6-12-2015

Date: 7-4-2021

Date: 23-4-2021

|

Nucleosome Organization or Content Can Be Changed at the Promoter

KEY CONCEPTS

- A remodeling complex does not itself have specificity for any particular target site, but must be recruited by a component of the transcription apparatus.

- Remodeling complexes are recruited to promoters by sequence-specific activators.

- The factor may be released once the remodeling complex has bound.

- Transcription activation often involves nucleosome displacement at the promoter.

- Promoters contain nucleosome-free regions flanked by nucleosomes containing the H2A variant H2AZ (Htz1 in yeast).

- The MMTV promoter requires a change in rotational positioning of a nucleosome to allow an activator to bind to DNA on the nucleosome.

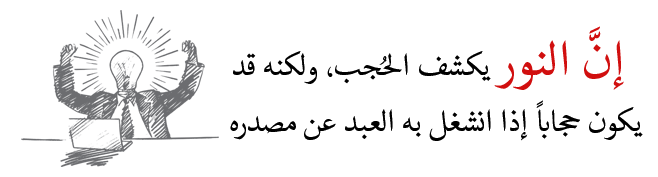

How are remodeling complexes targeted to specific sites on chromatin? Most remodelers do not contain subunits that bind specific DNA sequences, though there are a few exceptions. This suggests the model shown in FIGURE 1, in which remodelers are recruited by activators or repressors.

FIGURE 1. A remodeling complex binds to chromatin via an activator (or repressor).

The interaction between transcription factors and remodeling complexes gives a key insight into their modus operandi. The transcription factor Swi5 activates the HO gene in yeast, a gene involved in mating-type switching. (Note that despite its name Swi5 is not a member of the SWI/SNF complex.) Swi5 enters the nucleus near the end of mitosis and binds to the HO promoter. It then recruits SWI/SNF to the promoter. Swi5 is then released, leaving SWI/SNF at the promoter. This means that a transcription factor can activate a promoter by a “hit and run” mechanism, in which its function is fulfilled once the remodeling complex has bound. This is more likely to occur with genes that are cell-cycle regulated or otherwise transiently activated; it is equally common at many genes for transcription factors to remain associated with target genes for long periods.

The involvement of remodeling complexes in gene activation was discovered because the complexes are necessary to enable certain transcription factors to activate their target genes. One of the first examples was the GAGA factor, which activates the Drosophila hsp70 promoter. Binding of GAGA to four (CT)n-rich sites near the promoter disrupts the nucleosomes, creates a hypersensitive region, and causes the adjacent nucleosomes to be rearranged so that they occupy preferential instead of random positions. Disruption is an energy-dependent process that requires the NURF remodeling complex, a complex in the ISWI subfamily. The organization of nucleosomes is altered so as to create a boundary that determines the positions of the adjacent nucleosomes. During this process, GAGA binds to its target sites in DNA, and its presence fixes the remodeled state.

The PHO system was one of the first in which it was shown that a change in nucleosome organization is involved in gene activation. At the PHO5 promoter, the bHLH activator Pho4 responds to phosphate starvation by inducing the disruption of four precisely positioned nucleosomes, as depicted in FIGURE 2 . This event is independent of transcription (it occurs in a TATA mutant) and independent of replication. The promoter has two binding sites for Pho4 (and another activator, Pho2). One is located between nucleosomes, which can be bound by the isolated DNA-binding domain of Pho4; the other lies within a nucleosome, which cannot be recognized. Disruption of the nucleosome to allow DNA binding at the second site is necessary for gene activation. This action requires the presence of the transcription-activating domain and appears to involve at least two remodelers: SWI/SNF and INO80. In addition, chromatin disassembly at PHO5 also requires a histone chaperone, Asf1, which may assist in nucleosome removal or act as a recipient of displaced histones.

FIGURE 2. Nucleosomes are displaced from promoters during activation. The PHO5 promoter contains nucleosomes positioned over the TATA box and one of the binding sites for the Pho4 and Pho2 activators. When PHO5 is induced by phosphate starvation (–Pi), promoter nucleosomes are displaced.

A survey of nucleosome positions in a large region of the yeast genome shows that most sites that bind transcription factors are free of nucleosomes. Promoters for RNA polymerase II typically have a nucleosome-free region (NFR) approximately 200 bp upstream of the start point, which is flanked by positioned nucleosomes on either side. These positioned nucleosomes typically contain the histone variant H2AZ (called Htz1 in yeast); the deposition of H2AZ requires the SWR1 remodeling complex. This organization appears to be present in many human promoters as well. It has been suggested that H2AZ-containing nucleosomes are more easily evicted during transcription activation, thus poising promoters for activation; however, the actual effects of H2AZ on nucleosome stability in vivo are controversial.

It is not always the case, though, that nucleosomes must be excluded in order to permit initiation of transcription. Some activators can bind to DNA on a nucleosomal surface. Nucleosomes appear to be precisely positioned at some steroid-hormone response elements in such a way that receptors can bind. Receptor binding may alter the interaction of DNA with histones and may even lead to exposure of new binding sites. The exact positioning of nucleosomes could be required either because the nucleosome “presents” DNA in a particular rotational phase or because there are protein–protein interactions between the activators and histones or other components of chromatin. Thus, researchers have moved some way from viewing chromatin exclusively as a repressive structure to considering which interactions between activators and chromatin can be required for activation.

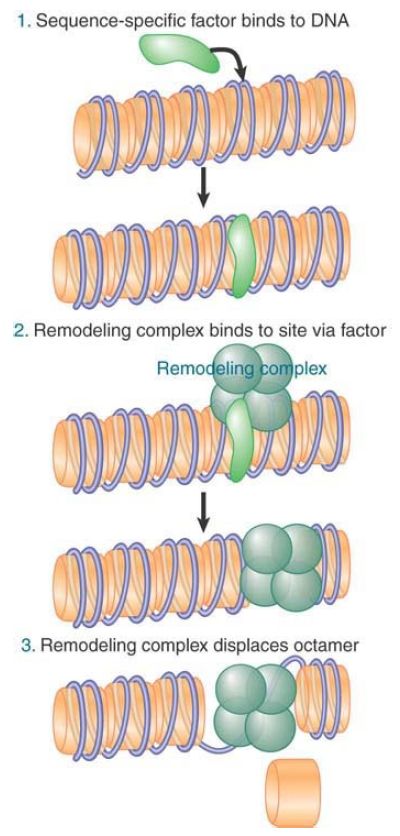

The MMTV promoter presents an example of the need for specific nucleosomal organization. It contains an array of six partly palindromic sites that constitute the hormone response element

(HRE). Each site is bound by one dimer of hormone receptor (HR). The MMTV promoter also has a single binding site for the factor NF1 and two adjacent sites for the factor OTF. HR and NF1 cannot bind simultaneously to their sites in free DNA. FIGURE 3 shows how the nucleosomal structure controls binding of the factors.

FIGURE 3. Hormone receptor and NF1 cannot bind simultaneously to the MMTV promoter in the form of linear DNA, but can bind when the DNA is presented on a nucleosomal surface.

The HR protects its binding sites at the promoter when hormone is added, but does not affect the micrococcal nuclease-sensitive sites that mark either side of the nucleosome. This suggests that HR is binding to the DNA on the nucleosomal surface; however, the rotational positioning of DNA on the nucleosome prior to hormone addition allows access to only two of the four sites. Binding to the other two sites requires a change in rotational positioning on the nucleosome. This can be detected by the appearance of a sensitive site at the axis of dyad symmetry (which is in the center of the binding sites that constitute the HRE). NF1 can be detected on the nucleosome after hormone induction, so these structural changes may be necessary to allow NF1 to bind, perhaps because they expose DNA and abolish the steric hindrance by which HR blocks NF1 binding to free DNA.

|

|

|

|

دراسة: إجراء واحد لتقليل المخاطر الجينية للوفاة المبكرة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"الملح والماء" يمهدان الطريق لأجهزة كمبيوتر تحاكي الدماغ البشري

|

|

|

|

|

|

بالصور: عند زيارته لمعهد نور الإمام الحسين (عليه السلام) للمكفوفين وضعاف البصر في كربلاء.. ممثل المرجعية العليا يقف على الخدمات المقدمة للطلبة والطالبات

|

|

|

|

ممثل المرجعية العليا يؤكد استعداد العتبة الحسينية لتبني إكمال الدراسة الجامعية لشريحة المكفوفين في العراق

|

|

|

|

ممثل المرجعية العليا يؤكد على ضرورة مواكبة التطورات العالمية واستقطاب الكفاءات العراقية لتقديم أفضل الخدمات للمواطنين

|

|

|

|

العتبة الحسينية تستملك قطعة أرض في العاصمة بغداد لإنشاء مستشفى لعلاج الأورام السرطانية ومركز تخصصي للتوحد

|