Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Word Formation Rules

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P262-C13

2026-01-31

17

Word Formation Rules

We introduced derivational morphology by saying that it changes one lexeme into another. A common way of representing this kind of process is by writing a WORD FORMATION RULE (WFR). While we begin with the intuition that a WFR changes one lexeme into another, we will argue that it is more helpful to think of the WFR as expressing a pattern of regular correspondence between pairs of lexemes.

Word Formation Rules must contain at least three kinds of information:

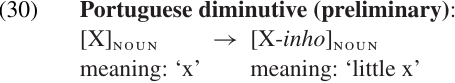

(a)the phonological effects on the base form (e.g. the shape of the derivational affix and where it is attached); (b) the semantic changes associated with this process; and (c) the syntactic category of the base (input) and of the resulting stem (output). To take a specific example, let us begin with the Portuguese diminutive suffix-inho. The WFR for this suffix might look something like (30).

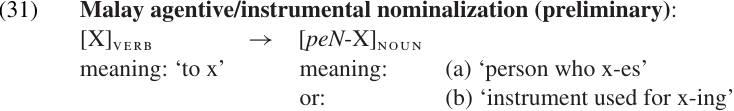

The “X” in this rule stands for the phonological shape of the base. The rule says that the suffix–inho can be added to a noun stem meaning ‘x’ to create another noun which means ‘littl ex.’ To take another example, let us consider the Malay prefix illustrated in (16–17), which derives nouns from verbs:

One way of interpreting a rule like (30) or (31) is to assume that only the base form is listed in the lexicon, while the derived form is produced by a rule of the grammar (specifically, a WFR). This would be similar in some ways to the distinction between words, which are listed in the lexicon, vs. phrases and sentences, which must be produced by Grammatical Rules.

However, many authors have pointed out that this view of word formation leads to a number of difficulties. It is more useful to assume that both forms are listed in the lexicon. We refer to the morphologically simpler form as the base, and the morphologically more complex form as the derived form, but both lexical entries are listed. Under this view, a WFR is an expression of regular correspondences between pairs of lexical entries.

It may seem surprising to think of every derived form (or lexeme) in the language as having a separate lexical entry, but adopting this hypothesis will help us to account for a number of characteristic properties of derivational morphology. Let us consider some of these properties. First, derivational morphology is lexically specific; specific affixes may apply to certain base forms and not to others within the same category. For example, a particular nominalizing suffix in English will apply to certain adjective stems but not to others: superior-ity vs. *superior-ness; truth vs. *true-ness; strange-ness vs. *strange-ity; firm-ness vs. *firm-th; etc. Similarly, the English prefix en- attaches to nouns and adjectives to create transitive verbs; but the set of base forms that take this prefix is fairly limited: encourage, enthrone, entitle, entangle, enliven, enlarge (cf. *em-big), embolden (*em-brave(n)), enrich (*en-wealth(y)), etc.

Clearly the lexicon must specify in some way which base forms can take which affixes. One approach might be to include a set of features in the lexical entry of each root to indicate which derivational affixes or combinations of affixes could be added to that root; but in any language with even a modest number of derivational affixes, this would add an enormous amount of complexity to the lexicon. By assuming that each lexeme is already listed in the lexicon, we avoid this problem. A WFR “applies” to a particular root or stem just in case the lexicon contains both the “input” form (the base) and the corresponding “output” (derived) form.

There are also cases where what looks like a derived form does not correspond to any actual base form. For example, words like ostracize and levity seem to end in derivational suffixes, but there are no corresponding basic forms in English (*ostrac,*lev). Similarly, disambiguate clearly contains the prefix dis-, but*ambiguate is not a real verb. Ambigu-ous and ambigu-ity are related to dis-ambigu-ate in meaning, but their common root(*ambigu-) does not exist. If each real word is listed in the lexicon, these examples are not a problem. There may be lexical gaps (i.e. non-existent forms) corresponding to either the base or the derived form for a particular WFR, but the rule can still help us to understand the meaning and structure of the forms that do exist.

As we noted, derivational morphology tends to be semantically irregular or unpredictable. German diminutive nouns sometimes have special meanings which could not be predicted from the base form alone: Frau ‘woman, wife, ’Fräulein ‘unmarried woman.’ The English word transmission can refer to the act of transmitting something (the predictable meaning), or to a specific part of a car (unpredictable meaning). Clearly the WFR itself cannot tell us everything we need to know about each specific derived form. But if each derived form is already listed in the lexicon, then any semantic, phonological, or other irregularities will be listed in the lexical entry for that particular form.

Our hypothesis also helps us to understand another aspect of word formation, namely, that speakers react to unknown or novel words as being “unreal” in some sense. Derivational affixes are occasionally used to create brand new words. The suffix-ize, for example, has been used to coin the word mesmerize (from the surname of an early pioneer in the practice of hypnotism, F. A. Mesmer) in the early 1800s; the word bowdlerize (from the name of Dr. T. Bowdler) a few decades later; and the term Balkanize, probably around 1915.

However, most of the time these affixes occur in words which are already known, that is, already part of the lexicon. If an English speaker produces anew word, e.g.? methodicalize, hearers will probably guess that it means ‘to make something methodical’ (cf. radicalize). But they are also likely to protest: “There is no such word.” This sense that certain possible derivations are not real words, the ability to distinguish between newly coined words and actual existing forms, gives additional support to our assumption that both input and output forms are already listed in the lexicon.

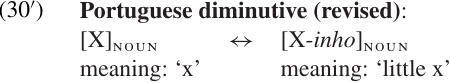

Under these assumptions, then, the Portuguese lexicon contains entries for both bandeira ‘flag’ and bandeirinha ‘pennant.’ The rule in (30) does not actually “create” a new stem; rather, it expresses a regular correspondence that exists between these two particular stems, and between many similar pairs. For this reason, it is somewhat misleading to show the rule as a one-way process. It would be more accurate to use a double arrow, as illustrated below, to indicate that the WFR expresses a two-way relationship.

One could say that word formation rules are redundant, in the sense that they do not add new entries to the lexicon. But this does not mean they are useless or unimportant. The fact that speakers can use WFRs creatively to coin completely new words, and that other speakers can understand these new words, shows that speakers in some sense (subconsciously) “know” these rules. Knowing the rules may also help speakers to recall and understand complex words more efficiently.

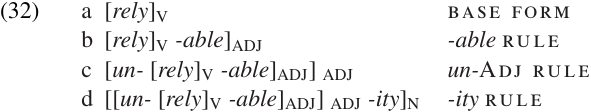

WFRs allow us to determine the morphological structure of stems, which is often important for both semantic and phonological interpretation. Consider the word unreliability. This stem clearly contains the root

rely although there is no single WFR which could express the relationship between the root and the derived form. It would take a sequence of several WFRs, applying in the correct order, to connect the two, as illustrated in (32).20 The use of labeled brackets, as in (32d), is a common way to represent the internal structure of a stem.

20. Since un- is the only prefix in this form, it may not be obvious that it needs to be attached at any particular stage of the derivation. However, we know that it cannot attach to nouns, so it cannot be added after-ity; there is no such verb as unrely; therefore, the only possible base in this example is the adjective reliable, as indicated in (32c). The change from–able to–abil when–ity is added is an example of ALLOMORPHY, which will be discussed in Allomorphy.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)