Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Productivity versus creativity

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

70-4

19-1-2022

3160

Productivity versus creativity

Some morphologists make a distinction between morphological productivity and morphological creativity. When processes of lexeme formation are truly productive, we use them to create new words without noticing that we do so. Similarly, when hearers are exposed to a productively formed complex word, they understand it, but usually don’t note that it’s a new word (at least for them). This is not to say that speakers and hearers never notice productively formed new words, just that often such words slip by without notice. Morphological creativity, in contrast, is the domain of unproductive processes like suffixation of -th or marginal lexeme formation processes like blending or backformation. It occurs when speakers use such processes consciously to form new words, often to be humorous or playful or to draw attention to those words for other reasons.

For example, speakers might use the unproductive suffix -th to form an adjective like coolth (in contrast to warmth), consciously trying to be clever or witty. Another example might be the suffix -some that occurs in English in words like twosome, threesome, and foursome. Theoretically this suffix might be infinitely productive because its bases are cardinal numbers. But it’s really only attached to the numbers two through four or five. We would probably only coin a new word like seventeensome if we were trying to be funny. Such a use would be creative, rather than productive use of this lexeme formation process.

Let’s now look more closely at the case of blending in English. Blending, as we saw, is the creation of new words by putting together parts of words that are not themselves morphemes. Relatively few blended words have become lexicalized words in English (brunch, smog), but the technique is frequently used for coining words by advertizers and the media, precisely because such words are noticeable. McDonald’s, for example, creates a word like menunaire from menu and millionaire to catch your eye (or ear), and make you pay attention to their pitch.

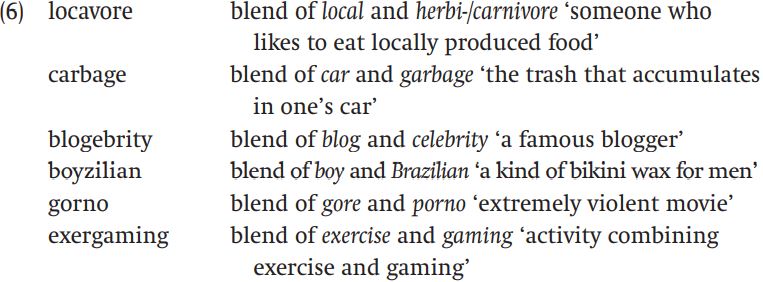

Websites that track new words often have a disproportionate number of blends, and most of those words are culled from the popular press. For example, in the new words posted on the Word Spy website (www.wordspy.com) from May 28 to July 10, 2007, there were six blends:

All six of these words were found in popular media – newspapers such as Newsday and The Plain Dealer, wire services (Associated Press), or magazines (The Economist). All were intended to catch the reader’s eye and therefore make for lively reading, and we might deem them successful because they found their way to Word Spy. In contrast, websites like Word Spy don’t pick up other new words with -ness. Word-spotters are far less likely to notice new forms that come from truly productive lexeme formation processes than new blends or the sporadic creative coinages that still come from unproductive processes.

As Bauer (2001) points out, however, it is not always possible to draw a sharp line between productivity and creativity. Take the diminutive suffix -let in English (booklet, wavelet, eyelet). A look at the Oxford English Dictionary suggests that this suffix enjoyed a vogue in the nineteenth century (over 200 first attestations in this century), but declined markedly in its productivity in the twentieth century (only 21 first attestations). Although these numbers may be a function of the current state of the dictionary – the third edition, which is likely to add new forms, is as yet incomplete – the numbers are still suggestive.2 The apparent marked decline in productivity may account for my sense that when a new form with -let is coined, it often sounds self-conscious. For example, in my household a very small poodle is referred to as a poodlet and a very small beagle as a beaglet; these forms are meant to be amusing, and I doubt that they would slip through unnoticed by anyone who heard us using them. Similarly, in a biography of Julia Child (great TV chef and cookbook author), her husband is quoted as referring to her as his wifelet – surely meant to be funny, as Julia was over six feet tall!3 If I’m right about this, this suffix may have slipped below the line of productivity, with new forms being marginal, and therefore perceived as creative.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)