Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

How to: analyzing allomorphy

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

165-9

25-1-2022

2295

How to: analyzing allomorphy

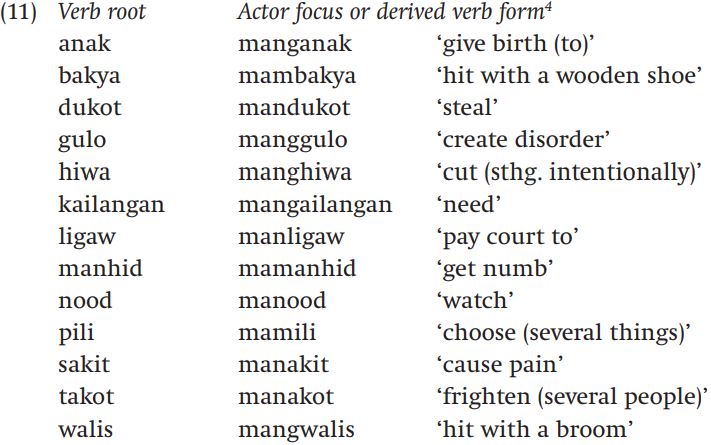

So far we’ve looked at allomorphy in English and a couple of other languages. In this section, we’ll take a close look at another language and see how morphologists go about analyzing allomorphy in a language that’s unfamiliar. Take a look at the data in (11) from the Philippine language Tagalog (Schachter and Otanes 1972: 290–1):

The first thing that should leap out at you when you see these data is that the forms in the right-hand column (let’s refer to them as the derived forms) seem to have some sort of prefix. But it’s not always exactly the same prefix. The prefix looks like mang- in the first form, mam- in the second, and man- in the third. There’s clearly some allomorphy displayed in this set of data.

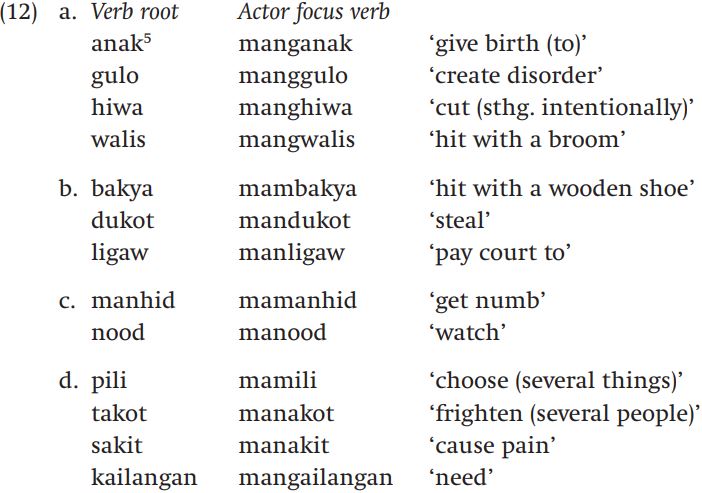

To see better what’s going on, it is often a good strategy to rearrange the data so that similar forms are put together. This allows you to begin to see patterns. There are a number of ways of doing this, but in (12), I’ve rearranged them into four groups. In the first, we can clearly segment off the prefix mang-. In the second group, it’s still possible to segment off a prefix and leave behind something that looks exactly like the verb root. What’s left over is either mam- or man-. The examples in (12c) look like something is missing, though. If we were just putting together a prefix with the stem, we might expect mammanhid and mannood, rather than the forms we actually find. And finally in (12d), we have forms in which the initial consonant of the verb root clearly seems to be absent.

Let’s start with the forms in (12a) and (12b) that are easily segmentable. Segmenting the derived verbs, we find the allomorphs mam-, man- and mang-. The first occurs on a root beginning with [b], the second with roots beginning with [d] and [l], and the third with roots beginning with [ʔ], [g], [h], or [w]. This far, the data should not surprise you: Tagalog seems to have a process of nasal assimilation, just as English and Zoque do. The labialfinal allomorph mam- occurs with a labial consonant, the alveolar-final allomorph man- occurs with alveolar initial roots, and the velar-final allomorph mang- occurs with roots that begin with either velar or glottal consonants. So far, things seem fairly neat.

When we turn our attention to the data set in (12c), however, we will see that there’s more to be said about the derived forms of the verb. It’s not so clear how to segment the forms in this set. Suppose we assume that the prefix is mam- or man-, as it was in (12a, b); we are then left with anhid or ood as allomorphs of the roots. Alternatively, we might assume that the prefix in these cases is just ma-. If we do so, then the bases would be exactly the same as the roots, namely manhid and nood. This might seem like the best solution at the moment – just adding another allomorph to the set we already have of mang-, man-, and mam-, but let’s keep our minds open to both solutions until we’ve finished looking at all the data.

The data in (12d) present us with a new problem. If we assume that Tagalog has nasal assimilation, we would expect that we would put together mam- with pili to get mampili and man- with takot to form mantakot, and so on. But instead we get mamili and manakot. The initial consonant of the stem seems to disappear when the prefix is attached. Now, if we look back and compare the verb roots that we find in (12b) and compare them to those we find in (12d), we will see that the former begin with voiced labial or alveolar consonants, whereas those in (12d) begin with voiceless consonants. It looks like when the prefix attaches to a base that begins with a voiceless consonant, the prefix first assimilates to the point of articulation of the following voiceless consonant, and then that consonant disappears.

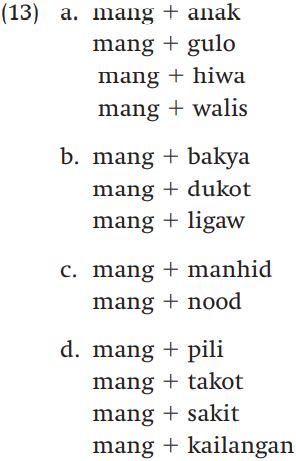

Here, we need to stop and think more about the nasal assimilation rule. I suggested that each set of allomorphs has a single underlying form, from which the others are derived by phonological rule. Since nasal assimilation in Tagalog seems to be a predictable process, we would assume this to be the case here as well. So we need to decide at this point what the underlying form should be. Remember that it’s often a good strategy to pick as the underlying form the allomorph that has the widest distribution, in other words the one that occurs with the most classes of sounds. Here, as the data in (12) show, the allomorph mang- occurs with glottal initial roots ([h] and [ʔ]), as well as with velars ([g], [k], [w]). The allomorph mam- occurs only with labial-initial roots ([p],[b]), and the man- allomorph only with alveolar-initial roots ([d], [t], [l]). We can reasonably make the hypothesis then that the underlying form of the prefix is mang-, since it occurs with two different classes of sounds. If so, then the forms in (12) have the following underlying representations:

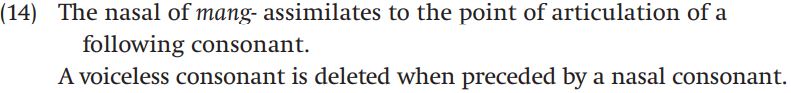

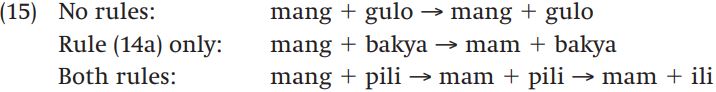

Now we can give an informal statement of two phonological rules that will derive the allomorphs from the underlying forms:

For the forms in (12a), neither rule applies. For those in (12b), only the first applies, since the verb roots don’t begin with voiceless consonants. But in (12d) both rules apply.

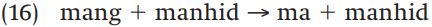

What about the examples in (12c), however? Remember that we were undecided as to whether the allomorph of the prefix should end in a nasal at all, and we were leaning towards the solution in which the allomorph was ma-, as it would allow us to say that the verb roots always had the same form. We can see now, however, that that might not be the right solution. Suppose that we were to assume that the correct allomorph is ma-; since we have postulated that the underlying version of the prefix is mang-, we would have to derive ma- from underlying mang-. This in turn would require us to add a third rule that would delete -ng before a nasalinitial verb root:

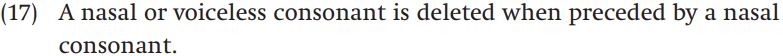

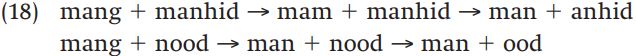

Before we add this third rule, however, let’s see what happens if we assume that for these bases the allomorphs for the prefix are mam- or man-. Note that we already have an assimilation rule that accounts for which of the allomorphs shows up – we get mam- before an m- initial root, and man- before an n- initial root. And we already have a rule that deletes consonants after a suffix that ends in a nasal. If we tweak that rule slightly, we can derive the forms in (12c) without adding a third rule:

The forms in (12c) can then be derived as follows:

So although it seemed at first that assuming the allomorph of the prefix in (12c) to be ma- made more sense, looking at the bigger picture, making the other choice allows us to derive all the allomorphs using a simpler set of rules. We assume then that this is the right solution. We must keep in mind, though, that we’ve only looked at a tiny set of data. If we were to continue looking at the morphology and phonology of Tagalog, we might decide that the analysis we’ve decided upon here needs to be revised again.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)