Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Characteristics of Germanic and non-Germanic derivation

المؤلف:

Andrew Carstairs-McCarthy

المصدر:

An Introduction To English Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

106-9

2024-02-05

2182

Characteristics of Germanic and non-Germanic derivation

It was noted that the inherited Germanic root heart is free while the cognate roots cord- and card-, borrowed from Latin and Greek, are bound, and the same applies to inherited bear by contrast with borrowed -fer and -pher. If this kind of contrast is general, then it has implications for inherited and borrowed affixes too. We will expect that native Germanic affixes should attach to free bases, while the affixes that attach to bound bases should generally be borrowed. And this turns out to be correct.

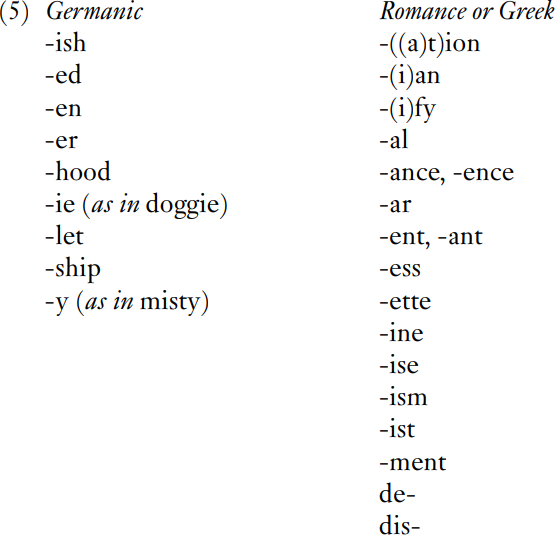

At (5) are listed most of the derivational affixes that we have considered so far, classified according to their origin:

It is easy to check that all the affixes in the lefthand column select exclusively or almost exclusively free bases, while most of those in the righthand column readily permit or even prefer bound ones. Compare, for example, -let and -ette, which are similar in meaning and in lack of generality: both mean roughly ‘small’, though neither is perfectly regular semantically, and -ette also sometimes means ‘female’. If you are asked to list nouns formed with the suffix -let, you will probably think of examples such as booklet, piglet, droplet and starlet, all with clearly identifiable free bases. For nouns with the suffix -ette, your list is sure to include cigarette, and it may also include (depending on your country of origin) suffragette, laundrette, kitchenette, maisonette and drum-majorette. Among these, the bases cigar-, laundr- and maison- are bound, cígar- (with stress on the first syllable) and laundr- being bound allomorphs of cigár and laundry, and maison- having no free allomorph in English. So, although -ette is by no means restricted to bound bases, it does not avoid them in the way that -let does. The word hamlet meaning ‘small village’ may seem to be a counterexample. However, if, like me, you feel this to be a simple word rather than a complex one, consisting of a single morpheme rather than a root ham- plus -let, it does not count as an actual counterexample. (Historically, in fact, hamlet was borrowed from French, and contained originally the -ette suffix in a variant spelling.)

Similar conclusions emerge from comparing some abstract-noun-forming suffixes in the two columns: -ship and -hood in the Germanic column, and -(a(t))ion, -ance/-ence, and -ism in the Romance and Greek column. For the latter, it is certainly possible to find words whose bases are free (e.g. consideration, admittance, defeatism); however, many of the bases selected by these affixes are bound, being either bound allomorphs of roots that are elsewhere free (e.g. consumption, preference, Catholicism) or else roots that lack free allomorphs entirely (e.g. condition, patience, solipsism). In contrast, nouns in -ship and -hood always seem to have free bases: friendship, kingship, governorship; childhood, adulthood, priesthood. What we observe here is, in fact, the historical basis for a phenomenon that we noted: the root of an English word is more likely to be free than bound, yet a large number of bound roots exist in modern English also, thanks to massive borrowing from French and Latin.

Describing the affixes in the second column, I was careful to say that most of them permit bound bases, not that all of them do. Some borrowed affixes associate solely or mainly with free bases, and in so doing have acquired native Germanic habits. An example at (5) is the suffix -ment, as in development, punishment, commitment, attainment – though it is sometimes found with a bound base, as in the nouns compliment and supplement. Another example is the prefix de-, as in deregister, delouse and decompose. This tolerance for free bases is surely connected with the fact that, de- is formally and semantically rather regular, and can readily be used in neologisms (e.g. de-grass in The courtyard was grassed only last year, but now they are going to de-grass it and lay paving stones). For an affix restricted to bound bases, such a neologizing capacity would be scarcely conceivable in a language where, as in English, most bases are free.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)