Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The reduction in inflectional morphology

المؤلف:

Andrew Carstairs-McCarthy

المصدر:

An Introduction To English Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

104-9

2024-02-05

2248

The reduction in inflectional morphology

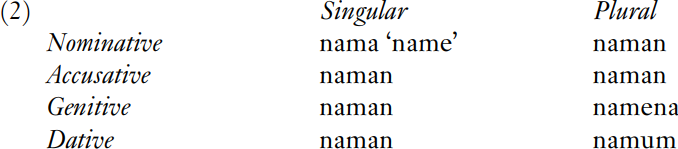

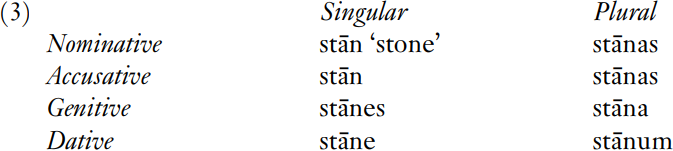

We noted that modern English nouns have no more than two inflected word forms: singular and plural. In Old English, however, there was superimposed on this number contrast a contrast of case, like that found in modern English personal pronouns (nominative we versus accusative us etc.), but more extensive: Old English nouns could distinguish also a genitive (or possessive) case, and a dative case whose meanings included that of modern to in Mary gave the book to John. These two numbers and four cases yielded a pattern of eight grammatical words for each noun lexeme, as illustrated at (2) and (3):

As will be seen, neither NAMA nor  had eight distinct word forms, one for each grammatical word; instead, they display different patterns of syncretism. However, all Old English nouns had more than the meager two forms that are available in modern English.

had eight distinct word forms, one for each grammatical word; instead, they display different patterns of syncretism. However, all Old English nouns had more than the meager two forms that are available in modern English.

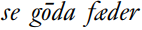

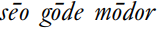

If nouns distinguished four cases in Old English, it is reasonable to guess that pronouns should have done so too; and that guess is correct. (In fact Old English pronouns sometimes had five cases, including an instrumental.) What is more, the same two numbers and four cases were available for adjectives and determiners (counterparts of words such as that and this), along with a distinction that has been lost in modern English: that of gender. As in modern German or Russian, Old English nouns were distributed among three genders (neuter, feminine and masculine), which were grammatically relevant in that they affected the inflectional affixes chosen by any adjectives and determiners that modified them. Thus, it is the distinction between masculine and feminine that accounts for the different forms of the words meaning ‘the’ and ‘good’ in  ‘the good father’ and

‘the good father’ and  ‘the good mother’.

‘the good mother’.

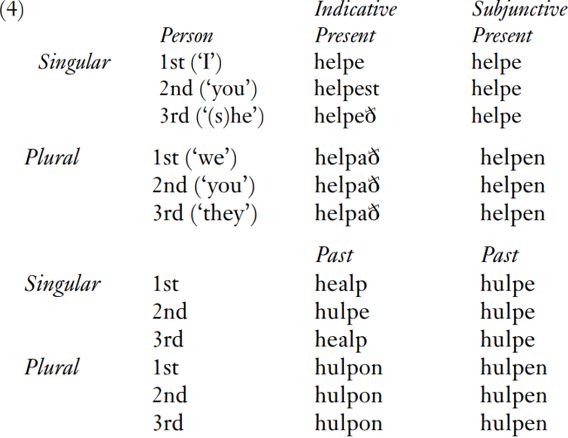

Old English verbs displayed a similar inflectional luxuriance. We noted that most modern English verbs have four distinct forms (e.g. perform, performs, performed, performing), while some common verbs have five (e.g. speak, speaks, spoke, spoken, speaking). By contrast, the typical Old English verb lexeme HELPAN ‘help’ had over a dozen distinct forms: a so-called ‘infinitive’ helpan ‘to help’, a perfective participle geholpen, and further forms including those whose grammatical functions are as set out in (4). (In (4), ´ stands for the sound represented by th in thin, and ‘indicative’ and ‘subjunctive’ represent a contast in mood: between, very roughly, asserting a fact (e.g. John is coming) and alluding to a possibility (e.g. … that John should come in I insist that John should come).)

Not included in (4) are the imperative forms (‘help!’), or the verbal adjective helpende, which, just like other adjectives in Old English, had forms that distinguished three genders, two numbers and four cases.

An obvious question is: why did English lose this wealth of inflection? Like many obvious questions, this one has no straightforward answer. Partly, no doubt, the loss of inflection is due to the temporary eclipse of English by French as the language of culture and administration after 1066, and hence the weakening of the conservative influence of literacy. Partly also it is due to dialect mixture. The examples of ‘Old English’ that I have given here come from the dominant dialect of written literature, that of south-western England. But this was not the dialect of London, which became increasingly influential during the so-called ‘Middle English’ period (from about 1150 to 1500), and established itself as the main variety used in printing. For example, the spread of the noun plural suffix -s at the expense of its rivals is a feature of northern dialects that affected the London dialect also. English inflectional morphology was already by 1600 almost the same as in 2000, so that modern readers of Shakespeare encounter only a few obsolete inflected forms such as thou helpest and he helpeth, for you help and he helps, that preserve two Old English suffixes illustrated in (2).

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)