تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

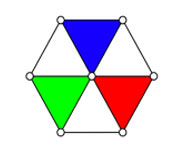

الهندسة

الهندسة

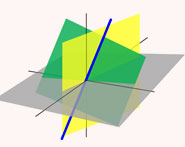

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 17-8-2017

Date: 17-8-2017

Date: 17-8-2017

|

Died: 21 July 1993 in Kingston, Tasmania, Australia

Edwin Pitman's parents were Ann Ungley Hooks and Edwin Edward Pitman. Both his parents were English and they met when they were on board a ship bound for Australia. The parents were emigrating to Australia and, after they reached Australia, they settled in Melbourne, married and had eight children, six girls and two boys. Edwin Edward worked for a firm making machinery. Edwin, the subject of this biography, was the fourth of his parents' children having three older sisters. Edwin's mother quickly realised that her son had a remarkable ability to retain information - she called him "that piece of blotting paper" - and although the family did not possess many books, Edwin loved to read books that he borrowed from his Sunday School teacher.

Pitman's early education was at Kensington State School, and from there he progressed to South Melbourne College. The College was rather remarkable, as Evan Williams relates in [6] (or [7]):-

On Saturday morning the boys would work through examination papers in Arithmetic and Algebra, including in the later years Cambridge Tripos papers; in the afternoons they would study Shakespeare. Even so, Edwin was dissatisfied with the course, believing that, although it was advanced it was not rigorous enough.

In his final year at South Melbourne College, the head of the College encouraged him to apply for residential scholarships for the University of Melbourne. He did so with great success, being awarded the Wyselaskie and the Dixson mathematics scholarships and well as an Ormond College Scholarship. He entered Ormond College, University of Melbourne, in 1916 and was taught by two outstanding lecturers. One was the New Zealander D K Pieken, who taught Pitman a rigorous understanding of the number systems. The other was Charles Weatherburn and we quote Pitman's own description of the way that he was taught by Weatherburn [4]:-

There were very few honours students, and I was the only Ormond student doing honours mathematics in my year. I went to his room once a week, and sat near his desk while he talked and wrote notes for me. Always he wrote on the back of foolscap paper, the front of which was filled with an early draft of a section of one of his books. He took me through the topics in his two books on vector analysis, and perhaps also some differential geometry ... He was neat and clear and interesting, and for me it was a very easy and efficient way of mastering vector analysis.

Of course, when Pitman began his university studies, World War I was already in progress. In fact it was near the end of the war before he had to put his studies on hold when, in 1918, he began war service with the 14th Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force. He was demobbed in 1919 but spent the year 1919-20 in London studying at the London School of Economics and also studying French and German at Berlitz College. He returned to Ormond College, Melbourne, in 1920 to continue his interrupted undergraduate studies. Again he was taught by Weatherburn but he also met statistics for the first time [1]:-

In a course called Advanced Logic at the University of Melbourne, Professor W R Boyce-Gibson, a very able philosopher and an excellent lecturer, devoted two or three lectures to [statistics]. I decided then and there that statistics was the sort of thing that I was not interested in, and would never have to bother about.

Pitman graduated with a B.A. with First Class Honours in Mathematics in 1921 and a B.Sc., mainly involving physics, in 1922. In that year he was appointed Acting Professor of Mathematics at Canterbury College, University of New Zealand. After spending 1922-23 in that role, he returned to Melbourne where he was awarded an M.A. in 1923. During session 1924-25 he was a tutor in mathematics and physics at Trinity College and Ormond College, and also a part-time lecturer in physics at the University of Melbourne. In 1925 he applied for the position of Professor of Mathematics at the University of Tasmania. This was one of the turning points in his career for, as he explained [1], at this point he became involved with statistics:-

Applicants were asked to state whether they had any knowledge of statistics, and if they would be prepared to teach a course in the subject. I wanted the appointment, so in my application I wrote, "I cannot claim to have any special knowledge of the Theory of Statistics; but, if appointed, I would be prepared to lecture on this subject in 1927."

Indeed, his application was successful and he took up the position of Professor of Mathematics at the University of Tasmania in 1926. It was a small university and, when he took up the post, the Department of Mathematics only had one part-time lecturer in addition to himself. This meant he had a very heavy teaching load giving courses in pure mathematics, applied mathematics and, after he had learnt enough statistics by reading books, he taught statistics courses. His study of statistics went further in 1928 when one of his part-time students, who also worked in the State Department of Agriculture, brought him some data on field trials of potatoes which he had analysed. The student, R A Scott, asked him to check that his analysis was correct before it sent it to John Wishart in Cambridge, which Pitman did. Not only did this mark the start of Pitman's collaboration with Scott and the State Department of Agriculture, but Scott also showed him a copy of R A Fisher's Statistical Methods for Research Workers.

In Tasmania he met Elinor Hurst, who graduated in Arts from the University of Tasmania. They married on 7 January 1932 and set up home in a large sandstone house on the edge of Hobart. They had four children: Jane, Mary, Edwin Arthur (Ted), and James (Jim). Three became academics, one of these a mathematician, one a statistician and the other an environmental scientist.

Pitman had no thoughts of publishing research articles at this stage in his career. In the first place he had not received any training in research and, in the second place, he was too busy with teaching and administration to add another string to his bow. However, in 1936 he was chairman of the Professorial Board and the university had received a grant from the government to promote scientific research. He wanted to be able to write a good end of year-one report and knew that only published articles would impress. He decided he better try to publish something and, as a first attempt, wrote a paper on hydrodynamics. However, he did not feel that it was good enough to even try to publish, so he made a second attempt with a statistics paper Sufficient statistics and intrinsic accuracy. The paper [6]:-

... defines the class of probability distributions that admits a complete sufficient statistic and also gives a critical account of the related concepts of information and intrinsic accuracy.

He sent the paper to John Wishart who he thought might remember his name through the State Department of Agriculture field trials. Wishart accepted the paper for publication in the Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society and it was published in 1936. This was the first of a series of eight papers which he wrote during the next two years which included: Significance tests which may be applied to samples from any populations (1937), Significance test which may be applied to samples from any populations. II. The correlation coefficient test (1937), and Significance tests which may be applied to samples from any populations. III. The analysis of variance test (1938). Another example is the paper A note on normal correlation (1939) which C C Craig describes as follows:-

Using the familiar fact that two simple linear combinations of two normally correlated variates are independently and normally distributed, an exact test is derived for the significance of the ratio of sample variances in samples from a normal bivariate population. The test contains only quantities calculable from the sample and can be put in the form of a Fisher's "t."

This sudden rush of published papers came to an end in 1939 when, with the start of World War II, Pitman lost a member of his department who was seconded for war work and he himself became an honorary Education Officer, No. 6 Recruiting Centre RAAF and later Wing Training Officer No. 6 Wing Air Training Corps. This involved him in travelling from Hobart to Evandale several times a week, a distance of about 170 km. He only returned to publishing after the war ended.

In 1947 he received an invitation to give lecture courses at two universities in the United States, Columbia University and the University of North Carolina. The family sailed to the United States in January 1948 where Pitman, for the first time, gave and attended research seminars. It is remarkable to think that by this time he had been a university lecturer for 26 years but had never given a seminar since he had never before had the opportunity to work with other statistics researchers. The family landed in San Francisco and, after travelling across that United States, Pitman taught for a semester at Columbia University in New York [1]:-

Abraham Wald was head of the statistics department. I had studied many of his papers, and learnt much from them. When I gave a seminar, he showed his mathematical power in the discussion afterwards. I realised that he had completely grasped what I had done. I admired him greatly, not only for his mathematical talent, but also for his great humility and kindness.

He next went to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where again he gave a course. He met Herbert Robbins at Chapel Hill and they wrote a joint paper Application of the method of mixtures to quadratic forms in normal variates (1949). After this he spent a few weeks at Princeton before returning to Australia. This was only the first of several visits Pitman made to the United States. He spent research visits at Stanford in 1957, Johns Hopkins in 1963, and Chicago in session 1968-69. He also visited the University of Dundee in Scotland, where he was a visiting senior research fellow, in 1973. In fact most of these visits were made after Pitman retired, which was in 1962 when he reached the age of sixty-five. Retirement, however, did not mean that he stopped undertaking research, rather it gave him more opportunities to travel and work on statistical problems. Some of his most significant work, which he did over several years, was on the Cramér-Rao inequality. In particular he was interested in the regularity conditions under which it holds and its use in comparing statistics as estimates of parameters. He published an important paper on the topic in 1978, namely The Cramér-Rao inequality. He was over eighty years of age at this time and he writes in [1] that his work here:-

... would seem to be the last word on this famous inequality.

In 1979, Pitman published a book entitled Some basic theory for statistical inference. C R Rao writes in a review:-

This book is based on lectures delivered by the author at various places on selected and somewhat unrelated topics in statistical inference. The emphasis is on rigour and elegance of proofs. ... the author's efforts in presenting the mathematical results with some elegance and precision are highly commendable. The book should be read by all those who teach statistical inference.

Pitman received many honours for his contributions to mathematics and statistics. He was elected president of the Australian Mathematical Society in 1958-59 and was made an honorary life member in 1968. Two years earlier he had been made an honorary life member of the Statistical Society of Australia and the Society now awards the Pitman Gold Medal as its highest honour. The first such presentation of the Pitman Gold Medal was made to Pitman himself in 1978. He was elected a fellow of the Australian Academy of Sciences in 1954 and, two years later, he was elected to the International Statistical Institute. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Statistical Society in 1965. The University of Tasmania, which he had served so well, awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1977.

As to Pitman's character, let us quote from Peter Sprent who was a student of Pitman's in the 1940s, going on himself to become a professor of statistics:-

On first acquaintance, I summed up Edwin Pitman as somewhat cool and aloof, perhaps a little indifferent to those around him. I was misled because Edwin was so highly organized and self-disciplined that he conducted himself - in public at any rate - with almost military precision. He would have achieved less both as an academic and as an administrator had he not led such a disciplined life. In his own University he was remembered as a key figure in a small group who steered an under-staffed, poorly financed and sometimes badly administered University through turbulent seas to calmer waters. ... Edwin's most endearing characteristic was modesty about his achievements. He gave a course on inference, culminating in a treatment of asymptotic relative efficiency, not even telling us it was his concept.

Spent also writes in [5]:-

Edwin had a flair for coining descriptive, often amusing, words or phrases to epitomize widely used or novel concepts, e.g. 'squariance' for 'the sum of squares of deviations from the mean' and 'loglihood' for 'the logarithm of the likelihood'. His eccentric limit theorem proved that the limiting distribution of the harmonic mean of independent variates having certain properties is the Cauchy distribution.

Finally, we note that in addition to mathematics and statistics, Pitman was very fond of gardening, music and drama.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

سماحة السيد الصافي يؤكد ضرورة تعريف المجتمعات بأهمية مبادئ أهل البيت (عليهم السلام) في إيجاد حلول للمشاكل الاجتماعية

|

|

|