تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

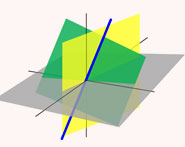

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 9-6-2017

Date: 13-6-2017

Date: 9-6-2017

|

Died: 17 March 1962 in Hamburg, Germany

Wilhelm Blaschke's father was Josef Blaschke who was a mathematician. Josef was professor of descriptive geometry at the Landes Oberrealschule in Graz. He favoured Steiner's approach to mathematics which was very much based on geometry and the belief that geometry alone stimulates thinking. Josef also favoured concrete geometrical problem over more abstract ones and he influenced his son Wilhelm to take a similar approach to mathematics. There is another way that Josef Blaschke influenced his son, which was significant given the problems that he would later face, and this was to give him an international outlook making him very open minded in his approach to those from different countries.

Wilhelm was brought up in Graz and it was there that he attended secondary school, graduating at the age of eighteen. He studied archirectural engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Graz for two years before going to Vienna to study under Wirtinger for his doctorate which was awarded by the University of Vienna in 1908. He then wanted to learn from all the leading geometers of the day and for many years he visited different universities learning from the experts in the subject. He spent some time in Pisa with Bianchi, then a semester in Göttingen with Klein, Hilbert and Runge. Following this he went to Bonn where he worked with Study, submitted his habilitation thesis and became a privatdozent there in 1910. In the following year he was on his travels again, going to work at Greifswald with Engel.

Blaschke became extraordinary professor of mathematics at the Deutsche Technische Hochschule in Prague in 1913, remaining there for two years before moving to Leipzig in 1915. In Leipzig he became a close friend of Gustav Herglotz who was interested in partial differential equations, function theory and differential geometry, and succeeded Runge in Göttingen 10 years later. While in Leipzig, Blaschke published Kreis und Kugel (1916) in which he investigated isoperimetric properties of convex figures. This work in particular shows how he was developing ideas due to Steiner who had worked on this topic but was subsequently criticised by Dirichlet for not giving existence proofs. Although Weierstrass had supplied the missing proofs using the calculus of variations, this did not satisfy Blaschke who gave proofs in the style of Steiner in Kreis und Kugel.

As with his previous position, Blaschke held the post at Leipzig for two years before moving on. This time he went to the University of Königsberg in 1917 where for the first time he accepted the position of full professor. Again Blaschke remained for about two years before moving to Tübingen. This was for a short time, however, since In 1919 he was appointed to a chair in the University of Hamburg, a post which he held for the rest of his career. We do not mean to suggest that Blaschke stopped his travels when he took up the post in Hamburg. On the contrary he continued to enjoy the "international" side of his character which came from his father, visiting universities and colleagues around the world, holding visiting professor position at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Chicago in the United States, the University of Istanbul in Turkey, as well as nearer home at the Humboldt University in Berlin. He married Augusta Meta Röttger and they had two children.

In Hamburg he built up an impressive school, managing to appoint mathematicians of the quality of Hecke, Artin and Hasse within a short period of time. Students flocked to study in the exciting environment which he created there. He began to take a leading role in mathematics in Germany, serving on various committees and we take a look at his work in some of these areas, in particular his role in the German Mathematical Society.

The International Mathematical Union had been in crisis over the participation of Germany, Austria, Hungary and Bulgaria, because of their role in World War I. An argument at the General Assembly of the International Mathematical Union during the International Congress of Mathematicians in Zurich in 1932 voted to suspend the Union and set up a Commission to discuss re-establishing it. Blaschke was appointed to the Commission as a member of the Executive Committee of the German Mathematical Society. His appointment came after Weyl, who had been on the Commission as Chairman of the German Mathematical Society, had taken up a post in the United States. However after Hitler came to power on 30 January 1933 the Nazi policies began to have a major impact on the German Mathematical Society and its members.

Reidemeister, who was professor of mathematics at Könisberg, was dismissed from his post having been declared "politically unreliable" by the Nazis. In June 1933 Blaschke organised a petition trying to persuade the government that forcing Reidemeister to retire at 40 years of age was detrimental to both the teaching of mathematics and mathematical research in Germany. Blaschke's petition was successful and Reidemeister was appointed to Hensel's chair at Marburg in what was considered a smaller and less prestigious university. More serious disputes followed, however, throughout 1934. Two sharply opposing views were put to the German Mathematical Society, one championed by Bieberbach being that they should enforce Nazi policies on German mathematics and race, the other led by Blaschke arguing that the Society should remain international, open and develop its policies for the best mathematical and not political reasons. Those wishing to enforce the Nazi policies, particularly dismissing Jewish professors, wanted to make Bieberbach Chairman for life. The arguments were bitter and Blaschke won the day being himself elected Chairman of the German Mathematical Society in September 1934. However Bieberbach managed to prevent changes to the statutes of the Society that Blaschke attempted to introduce and the Reich Ministry of Education intervened forcing both Bieberbach and Blaschke to resign. Blaschke resigned the Chairmanship of the German Mathematical Society in January 1935 and at the same time also resigned from the Commission set up by the International Mathematical Union.

Although up to this time Blaschke had strongly resisted certain Nazi policies, he seems to have had a change of heart in 1936. He made approaches to the Nazi party in 1936 which saw him become a party member and take a leading role in German mathematics until the end of World War II. It does seem that his approaches to the Nazis was not simply based on giving support so that he would be able to take a leading role in German mathematics. He described himself as "a Nazi at Heart" and was nicknamed Mussolinetto by his colleagues in Hamburg for his fascist sympathies, so there seems little doubt that he did join the Nazi party because he believed in what they stood for.

Anschluss, political union of Austria with Germany, had long been supported by Austrian Social Democrats. It was a process which Blaschke certainly supported, so when Germany invaded Austria on 12 March 1938 and Hitler annexed Austria on the following day, Blaschke approved. He wrote in the preface of one of his books:-

Whereas earlier volumes of mine on differential geometry appeared in murky times, this book was completed as a dream of my youth was fulfilled, the union of my more narrowly seen homeland, Austria, with my larger homeland, Germany.

In fact when the Germany invasion of Austria occurred Blaschke was on a visit to Messina in Italy and the political events must have presented him with an awkward situation. He went to Italy, where he gave a series of lectures, before going on to Greece where again gave several lectures before returning to Germany on 16 April. Blaschke was at this time in the rather difficult position of still being viewed with suspicion in Germany given his fight for internationalism. However, given the German invasion of Austria and other events, as a German who had openly supported the Nazis he would be treated with suspicion when abroad.

In 1939 Blaschke took part in a Congress in Rome from 22 to 28 October. By this time World War II had begun following the German invasion of Poland on 1 September. Blaschke had made an attempt to prevent Bieberbach being named by the Reich minister as head of the German delegation, fearing that such an appointment would create trouble with both German and Italian mathematicians. However, Blaschke did not object to Bieberbach participating in the Congress. Blaschke, who had made a lecture tour of Italy in the summer of 1942 and was awarded an honorary degree by Padua University at that time, returned to Italy later that year to attend another Congress in Rome from 9 to 12 November 1942, This was at the time when the fighting of World War II was at its most intense. Although described as an international congress, only a few specially invited foreigners attended and Blaschke was one of a small number of Germans who were invited.

On 28 July 1943 Blaschke went on holiday to the Tyrol with his wife. On the following day his house in Hamburg was completely destroyed in a bombing raid. He was at this time Dean in Hamburg, but tried hard to avoid returning because of the danger. After he returned in October there were moves to dismiss him as Dean because of his attempts to be in a safer location which eventually happened. World War II ended officially on 8 May 1945 after surrender of the German forces and on 3 September 1945 the allies dismissed Blaschke from his chair at Hamburg on the recommendation of several other mathematicians who criticised the way that Blaschke had influenced appointments. A report to the Hamburg university senate reads:-

Although he cannot be described as a typical National Socialist, he used political pressure on issues of appointments. The rector indicates Blaschke's old sympathies with fascism.

He was also accused of encouraging the publisher Springer to support Nazi policies in a way that mathematicians had been disadvantaged. However, others such as Carathéodory argued that Blaschke should be reinstated so that relations among German mathematicians might improve. However the accusations against Blaschke were made more because his colleagues knew that he had Nazi sympathies rather than because he had done anything which caused harm to others. After Blaschke appealed against his dismissial he was reinstated on 23 October 1946 and continued to hold his chair in Hamburg until he retired on 30 September 1953.

Blaschke's research was on various aspects of geometry. Scriba writes [1]:-

One of the leading geometers of his time, Blaschke centered most of his research on differential and integral geometry and kinematics. He combined an unusual power of geometrical imagination with a consistent and suggestive use of analytical tools; this gave his publications great conciseness and clarity and, with his charming personality, won him many students and collaborators.

He wrote an important book on differential geometry Vorlesungen über Differentialgeometrie (1921-1929) which was a major 3 volume work. The first volume considered classical geometry, while the second volume was on affine differential geometry. This volume was essentially a record of the contributions which Blaschke and his students had made to this topic, for it was a topic which eh had introduced and developed. The third volume of Vorlesungen über Differentialgeometrie considered geometry which originated from the action of various transformation groups, such as those of Möbius, Laguerre and Lie. This volume, in particular was totally in the spirit of Klein's Erlangen Program.

He also initiated the study of topological differential geometry, the study of invariant differentiable mappings. Again he wrote major texts which put together the many results which he had obtained, Geometrie der Gewebe was published in 1938, while after he retired he wrote another text on this topic namelyEinführung in die Geometrie der Waben which was published in 1955.

In addition to an honorary degree which he received from Padua, which we mentioned above, Blaschke also received honorary degrees from Sofia University, Greifswald University and Karlsruhe Technische Hochschule. Had it not have been for World War II it is likely that Blaschke would have received further honours from countries which chose not to honour him for political reasons.

Articles:

|

|

|

|

5 علامات تحذيرية قد تدل على "مشكل خطير" في الكبد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اللجنتان العلمية والتحضيرية تناقش ملخصات الأبحاث المقدمة لمؤتمر العميد العالمي السابع

|

|

|