تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

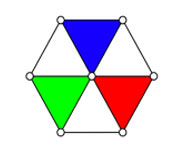

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

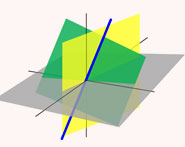

الهندسة

الهندسة

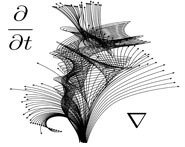

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 26-4-2017

Date: 7-5-2017

Date: 27-4-2017

|

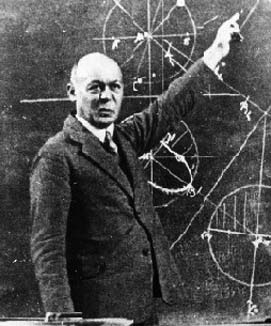

Died: 21 August 1933 in Zakopane, Poland

Leon Lichtenstein was born into a Jewish family. He was related through Leo Wiener (1862-1939), an American historian, linguist and author, to Norbert Wiener. Leo Wiener was Norbert Wiener's father and Leo Wiener's mother Freda was related to Leon Lichtenstein, the subject of this biography, who was her first cousin. Leon attended Mr Pankiewicz's High School in Warsaw, then attended the supplementary classes for science in the state-owned school in Jezuicka Street, graduating in 1894. Then he went to Berlin where he began his studies in mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin-Charlottenburg. After one year of study he left Berlin and returned to Warsaw where he became an apprentice at J Fajan's factory which made printing presses. After one year as an apprentice, he served for a year as a volunteer in the Russian army.

After his army service, he returned to Warsaw where he worked as an apprentice in the Repphan factory which made machines and pumps, being in the design office run by Mr Slucki. In the spring semester of 1898 he enrolled again at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin-Charlottenburg and he graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1901. He remained at Technische Hochschule where he studied electrical engineering for a year. He entered a competition to produce a scientific paper, submitting three items. One paper, entitled Cogito ergo sum, was given an award. The judges commented that (see [15]):-

... the paper is laudable from many points of view. Its author has a comprehensive and well-ordered knowledge of the literature of the subject and a vast mathematical knowledge, the application of which, not only in obtaining positive results, but also in criticising other approaches, makes one expect that he would be successful in his further research.

In the autumn of 1902 he was employed as an electrical engineer at the Siemens and Halske factory. Siemens, which began as a telegraph company, had diversified into electric trains and electric light bulbs. In 1903, a year after Lichtenstein joined the company, it merged part of its activities with Schuckert and Co. of Nuremberg and became Siemens and Schuckert. Lichtenstein spent three years as an electrical engineer in the research laboratory of Siemens which made electrical motors, followed by a year as a theorist in the electric railway department. In 1906 he was made head of the factory making electric cables.

From the time he began working at Siemens, Lichtenstein began to study mathematics. At first he studied on his own but, from 1906, he registered as a student at the University of Berlin. He attended lectures by Hermann Schwarz, Georg Frobenius, Edmund Landau and Friedrich Schottky. In 1907 he passed the maturity examination and, in the same year, earned a doctorate in Technical Sciences. In 1908 he graduated with a doctorate in electrical engineering from the Technische Hochschule in Berlin-Charlottenburg for his thesis Beiträge zur Theorie der Kabel: Untersuchungen über die Kapazitätsverhältnisse der verseilten und konzentrischen Mehrfachkabel (Contributions to the theory of electrical cables: Studies on the capacity ratios of concentric stranded and multiple wires). On 24 July 1909 he was awarded a doctorate in mathematics from the University of Berlin for his thesis Zur Theorie der gewöhnlichen Differentialgleichungen zweiter Ordnung. Die Lösungen als Funktionen der Randwerte und der Parameter (On the theory of differential equations of the second order. The solutions as functions of the boundary values and the parameter). In 1910 he habilitated at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin-Charlottenburg with his thesis Beweis des Satzes, dass jedes hinreichend kleine im wesentlichen stetig gekrümmte singularitätenfreie Flächenstück auf einen Teil einer Ebene zusammenhängend und in den kleinsten Teilen ähnlich abgebildet werden kann. However, he continued to keep his position at Siemens.

Along with Constantin Carathéodory, Gerhard Hessenberg and Edmund Landau, Lichtenstein was an editor of Mathematische Abhandlungen Hermann Amandus Schwarz which was being published by Springer Verlag. Before this work was published (it appeared in 1914) Ferdinand Springer discussed with Lichtenstein about publishing work on the theory of boundary value problems. Lichtenstein replied suggesting publication of a complete survey of mathematics, split into twelve subject areas. He also suggested possible authors for these areas including Otto Blumenthal, Harald Bohr, Richard Courant, Issai Schur, and Hermann Weyl. Ferdinand Springer did not reply immediately but he wrote at the beginning of August 1914, a few days after World War I had begun [2]:-

I must report for active duty in the next few days and must therefore let your kind proposal lie dormant for the moment. I hope we will meet again in peace-time and can then pursue your suggestion further.

It was not only Ferdinand Springer who had to undertake war work, for so did Lichtenstein. He was still employed by Siemens and the firm was very much involved in war work. Lichtenstein's war work included testing power cables and doing aerodynamic calculations for the Air Force. However, by the summer of 1917, Lichtenstein's ideas for a new mathematical journal were taking shape and a contract was signed with Springer Verlag for the new journal Mathematische Zeitschrift with Lichtenstein as executive editor and the other editors being Konrad Knopp, Erhard Schmidt and Issai Schur. They planned to produce the journal with four parts each year, a part consisting of between 96 and 112 pages. The editors sought papers and in, July 1917, they sent the first manuscript to the printers. However, most of Springer Verlag's expert printers were still in the armed forces so it took some time before the first part could be printed. However, the first part of Mathematische Zeitschrift appeared in 1918.

In 1919, after the war had ended, Lichtenstein became a full honorary professor at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin-Charlottenburg. In that year he took on another editorial duty, in addition to that of executive editor of Mathematische Zeitschrift [1]:-

From 1919 to 1927, moreover, Lichtenstein was chief editor of the 'Jahrbuch über die Fortschritte der Mathematik', which at the time was the only publication that included brief summaries of all German mathematical literature as well as a large part of what was being published internationally in the field of mathematics.

Emil Lampe (1840-1918) had been the editor of the Jahrbuch since 1885 but he died in 1918 and, after Arthur Korn (1870-1945) stood in for a year as a temporary editor, in early 1919 Lichtenstein took over as editor. Hilda Geiringer, who later married Richard Von Mises, spent two years assisting Lichtenstein with his editorial duties. The war had made publication of the Jahrbuch a very hard task and Lichtenstein took over in the most difficult of circumstances. However, he was highly successful in steering the Jahrbuch to great success. A high scientific level was particularly close to his heart and, under his leadership, numerous eminent scholars contributed to the yearbook.

In 1920 David Hilbert named Felix Hausdorff, Ludwig Bieberbach and Leon Lichtenstein as suitable candidates for the 2nd and 3rd position in the appointments list in Kiel. Lichtenstein was not appointed but, in the same year, he was appointed as a full professor at the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität in Münster. Now that he had a position as a full professor, he resigned his position at Siemens and Schuckert having been employed there for eighteen years. However, he did not work for long at Münster for, in 1921, he accepted the chair of mathematics at the University of Leipzig.

We should now look at Lichtenstein's mathematical contributions. He did pioneering work in potential theory, integral equations, calculus of variations, differential equations and hydrodynamics. We quote the excellent summary of his contributions given in [1]:-

[Lichtenstein] made important contributions to the theory of partial differential equations, and the calculus of variations. The so-called "Schauder bounds" in the theory of elliptic differential equations can already be found quite precisely, for the two-dimensional case, in Lichtenstein's encyclopaedia articles. Lichtenstein's optimal theorem on the introduction of conformal parameters is well-known. His tracing back of a class of integro-differential equations to a system of integral equations was of far reaching importance. His hydrodynamics textbook, ... includes many of Lichtenstein's original results, especially in the chapter "Existenzsätze" [Existence theorems]. ... He was particularly intrigued by the problem of equilibrium figures of rotating liquids, which has been analysed repeatedly since Newton. In this field he proved several general existence and stability theorems, e.g. the existence of an equilibrium figure which corresponds to the separation of a moon from its mother planet. By observing the ramification near any given equilibrium figure, which in contrast to Lyapunov's studies does not have to be an ellipsoid, he managed to advance a new integro-differential equation and to work out more clearly the basic ideas of ramification. Lichtenstein's methods have therefore contributed significantly to the development of non-linear functional analysis.

In 1929 Lichtenstein published Grundlagen der Hydromechanik. This work on hydrodynamics was well ahead of its time in that two of the eleven chapters in the book are devoted to topological ideas. For many years following its publication insufficient knowledge led to these ideas not finding favour but recent work on topology and knot theory have shown that Lichtenstein laid the foundation for new developments in the qualitative study of fluid mechanics. Francis Murnaghan writes in the review [11]:-

This book by the well known mathematician of the University of Leipzig constitutes volume 30 of the Springer collection, 'Die Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften in Einzeldarstellungen'. As might be expected, it is very different from every other treatise on hydrodynamics. For the author, the fundamental problem of hydrodynamics is the integration of certain systems of partial differential equations with assigned boundary conditions, and he calls to his aid all the resources of modern mathematics. This makes necessary a large amount of preliminary material; the first chapter is devoted to topology, the second gives a brief but interesting account of vector analysis, the third treats potential theory, a subject to which the author has made valuable contributions, and so on. It is not until we reach page 290 that the equations of motion are derived. One of the most interesting and important chapters of the book is that devoted to the propagation of discontinuities, a difficult subject, the understanding of which is essential to any comprehension of wave motion. The last chapter is devoted to existence-theory questions. The book could not profitably be recommended to a beginner, but to one who has studied Lamb and who wishes to understand more fully the mathematical foundations of the subject it should prove very valuable. For practical applications of the theory one must still turn to Lamb and to some such book as Tietjens' account of Prandtl's lectures on hydro- and aero-mechanics. The printing has the degree of excellence we have come to expect in the books of the Springer collection.

Lichtenstein published the monograph Vorlesungen über einige Klassen nichtlinearer Integralgleichungen und Integrodifferentialgleichungen nebst Anwendungen in 1931. Jacob David Tamarkin writes in the review [20]:-

This monograph contains extremely rich material and introduces the reader into many theories of high importance. It represents a modified and magnified reproduction of a course of lectures delivered in 1931 by invitation at the University of Lwów.

In 1933 Lichtenstein published Gleichgewichtsfiguren rotierender Flüssigkeiten in which he collected all the work that he had done on the theory of rotating fluids since 1918. Elton James Moulton (1887-1981), Professor of Mathematics at Northwestern University in the United States, begins a detailed review as follows [10]:-

This important work of the late Professor Lichtenstein was published not long before his death. In it he has given a somewhat brief historical account of work done on the problem by his predecessors, and a fuller account of the contributions made by himself and his students during the last few years. Since he presupposes on the part of his readers a familiarity with the theory of the Newtonian potential function and of integral equations, together with a good grasp of other branches of analysis, geometry, and celestial mechanics, the book is not easy to read, but the results are so significant that it should be carefully studied by everyone who is seriously interested in the mathematical treatment of the problem of figures of equilibrium of rotating fluid bodies.

Lichtenstein spent the rest of his career at Leipzig where he supervised several students who became leading mathematicians. These students included Ernst Hölder (1901-1990), the son of Otto Hölder, Erich Kähler, Aurel Wintner, Hans Schubert, Hermann Boerner (1906-1982) and Karl Maruhn (1904-1976).

Lichtenstein was married to Stefania, who had a doctorate in psychology. Danuta Przeworska-Rolewicz writes in [15]:-

Leon Lichtenstein spent almost all his life outside Poland, but he was very closely linked to his mother country, was all the time in close contacts with Poland and showed lively interest in Polish sciences and culture. At home, he talked with his wife in Polish. Various fellowship holders, not only mathematicians, availed themselves of his hospitality when in Leipzig. He used to visit Warsaw and attended the mathematical congresses in Lwów (1927) and in Warsaw (1930). He contributed twenty papers to Polish scholarly periodicals, eight of which were in Polish. ... He was glad to receive an invitation to teach for one trimester at the Jan Kazimierz University in Lwów [now the Ivan Franko University of Lviv] in 1930, where his lectures were on the theory of integral and integro-differential equations.

Stefan Banach and Stanislaw Mazur attended his lectures in Lwów. In 1928 Lichtenstein had resigned from his role as editor-in-chief of the Jahrbuch über die Fortschritte der Mathematik. The events of 1933 were devastating for the Jewish Lichtenstein. After Hitler came to power the Nazi party organised Boycott Day on 1 April 1933. Jewish shops were boycotted and Jewish professors and lecturers were not allowed to enter the university. On 7 April 1933 the Nazis passed a law which, under clause three, ordered the retirement of civil servants who were not of Aryan descent, with exemptions for participants in World War I and pre-war officials. Lichtenstein decided that he would not wait to be dismissed [he was told that he would be deprived of his chair on 1 September 1933] but left Leipzig and returned to his native land, going with his wife Stefania to Zakopane in Poland. He had plans to devote himself to research in the peace and quiet of the mountain town, but sadly he was only there a short time before he developed heart and kidney problems and died in August 1933. He had planned to attend the Swiss Mathematical Congress in early September 1933 and had already written the lecture he planned to give entitled Zur Mathematischen Theorie der Gestalt des Weltmeeres. This lecture, giving a new approach to the theory of equilibrium figures, was edited and published in 1936, three years after his death.

Let us end with the tribute given in [21]:-

His kindness, helpfulness, simplicity, modesty, and the love of the discipline to which he had dedicated all his life won him respect and affection from all those who were lucky enough to know him well.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي للقرآن الكريم يقيم جلسة حوارية لطلبة جامعة الكوفة

|

|

|