تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

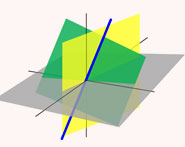

الهندسة

الهندسة

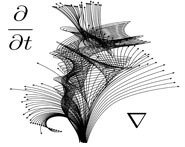

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 25-2-2017

Date: 25-2-2017

Date: 28-2-2017

|

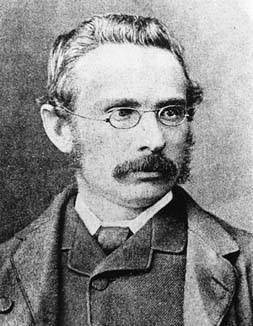

Died: 3 November 1911 in Edinburgh, Scotland

George Chrystal's father, William Chrystal, was first a grain merchant, later a landowner and farmer. His mother, Margaret Burr, was a daughter of James Burr of Mains of Glaik, Aberdeenshire. The family stayed at Mill of Kingoodie, and Chrystal received his early education at the parish school of Old Meldrum, two miles from his home. As a child he was bright intellectually but suffered from lameness, which he afterwards outgrew, but which prevented him from joining in physical games.

The family moved to Aberdeen shortly before 1863, the year Chrystal entered Aberdeen Grammar School. In 1866 he was awarded the Williamson Scholarship as the best pupil in the third class and, in his fourth and final class in the Grammar school he won the Silver Medal. In the same year, 1867, he enteredAberdeen University. Chrystal described his own experience at there [4]:-

When I entered the University of Aberdeen some eighteen years ago I was a moderate classical scholar, but I had learned practically no mathematics. We used to read the first book of Euclid as far as pons asinorum; but regularly as we reached the dreadful pass we were turned back for a revisal. Algebra I had none, not to speak of other mathematical furniture. Yet large demands were made upon me during my second session under Professor Fuller, and I had to work hard during the spare time of my first year to be able to take his junior class with advantage. The fact that mathematical students from Aberdeen had been doing well in the world long before the time I allude to, was due to no exertions on the parts of the schools, but simply to the presence in the Faculty of Arts of two teachers, Professors Fuller and Thomson, of exceptional energy and ability, whose efforts were ably seconded by a private tutor, Mr Rennet, well known and much beloved by all Aberdeen graduates, who combined in a way more happy than common the power of dealing at once with the best and with the worst material that came up to the university. With regard to the rest of the teachers of my first alma mater, I have this to say, that I entered their lecture rooms a child intellectually, and that I have emerged as a man, and that during no other part of my mental life have I made so much intellectual progress as I did under their tuition.

Chrystal graduated from Aberdeen in 1871 with first class honours in mathematics and natural philosophy, and received the Town's Gold Medal given to the best student of the year. He also won an open scholarship to Peterhouse, Cambridge which he entered in 1872. There he was greatly influenced by Maxwell who had been appointed Cavendish Professor in Experimental Physics in the previous year.

Chrystal wrote [6]:-

When I went to the University of Cambridge, I found that the course there for the ordinary degree in Arts was greatly inferior in educational quality to the Scottish one. On the other hand, the courses in honours were on a very much higher standard, although they suffered greatly from the chaotic organisation of the English universities which, about that time, were, to use a mathematical phrase, passing through a minimum turning point in their history. I might liken the difference between the English and Scottish university courses at that time to the difference that then existed between their national styles of cookery. The Scottish cuisine was characterised by lightness and variety, the English cuisine was noted for plenty and excellence of material, but lacked variety, and the defective preparation of its dishes often left them heavy and indigestible. I have frequently been tempted to think that the three years I spent as an undergraduate at Cambridge were wasted years of my life, if they were to be valued merely by the amount of new knowledge acquired, no doubt they were largely wasted, but, on the other hand, they were of great advantage to me in other respects. I made the acquaintance of a large number of the ablest young men of my generation... .

Chrystal graduated from Cambridge on 30 April 1875 and he was second wrangler placed equal with Burnside (John William Lord of Trinity was first wrangler). On 10 February 1875, Chrystal became second Smith's prizeman, the first Smith's prize being given to Burnside. The examiner for the Smith's prizes was Stokes. Shortly after his graduation, Chrystal was elected a fellow and lecturer of Corpus Christi College. For two years he lectured on mathematics and physics to the students of a number of colleges which included both Corpus and Peterhouse. Besides teaching he continued working in the Cavendish Laboratory under the supervision of Maxwell on the experimental verification of Ohm's Law.

In the summer of 1877 the chair of mathematics in the University of St Andrews became vacant and Chrystal applied for the post. With outstanding references from Maxwell, Thomson, Stokes and others he was appointed. Being the Regius Chair of mathematics it was a crown appointment and Chrystal received a telegram from the Home Secretary on Saturday 3 November 1877 informing him that he was successful.

At St Andrews he showed himself to be a very successful teacher. In addition to teaching he completed articles Electricity and Electrometer for the ninth edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica . In 1879 two further articles Galvanometer and Goniometer were published in Encyclopaedia Britannica, and from this time he became a permanent contributor to the Ninth Edition of the Encyclopaedia, his other main article Magnetism being published in 1883. On 26 June 1879 Chrystal married Margaret Ann Balfour, whom he had known from his childhood. The marriage took place in Bonn in Germany.

Before leaving for Germany to marry, Chrystal applied for the vacant chair of mathematics in the University of Edinburgh. He was appointed on 18 July and gave his inaugural address on Thursday 30 October 1879. Chrystal chose as his subject The History of Mathematics, talking in particular about the former occupants of the Edinburgh chair of mathematics. Chrystal was to hold the Edinburgh chair for the rest of his career. In 1891 he was appointed Dean of the Faculty of Arts and he carried through important educational reforms giving students complete freedom of choice and providing equality of subjects. He wrote [5]:-

Ever since I became convinced that a majority of educated Scotsmen desired to break down the old curriculum of seven subjects, my watchword has been "Greater freedom and higher standards". It is obvious that in any subject which is generally compulsory the standards cannot be high. I was never very anxious that all Arts students, should take either mathematics or natural philosophy; but I have all along striven to secure, so far as possible, that those who do take these subjects should be well prepared to receive them. To meet the difficulty of those who desired to have no mathematics, I proposed that an alternative should be given of a physical or natural science with practical or laboratory work; that mathematics should be entered on the higher standard, and that natural philosophy should remain as Newton made it and Gregory expounded it.

Despite holding the chair of mathematics at Edinburgh, Chrystal continued his interest in experimental work there. Knott, who was appointed as Tait's assistant, wrote of Chrystal [3]:-

It was my first year as Tait's assistant, and the incursion of this young professor of twenty-eight years into our midst gave all our minds a new orientation. His constant presence in the laboratory during the summer months and his ready accessibility at all times gave a great impetus to the experimental study of electricity and magnetism. ... Summer after summer Chrystal flitted through these laboratories, busy with his own researches, but not too busy to take a keen interest in all that was being done. Many a helpful suggestion he gave for new lines of work, and many an eager student did he encourage by inviting his co-operation in some special bit of investigation. The advanced students of these years came into more direct contact with him than with Tait, and much of their scientific progress was due to his sympathetic help. My own research work in magnetism, which has continued over many years, had its origin in a conversation over a passage in [Chrystal's] article 'Magnetism'.

Chrystal was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh on 2 February 1880. Most of Chrystal's published papers appear in the publications of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In November 1880 he was elected to the council of the Society. This was the first of three terms he served on the council (1880-3, 1884-7, 1895-1901), succeeding Tait as General Secretary of the Society in 1901. It was in this role that he had to fight hard for the Society. He wrote to Larmor on 13 November 1906 [9]:-

I hope you will by your presence support a deputation next week to the Secretary for Scotland to make a last appeal for justice to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in the matter of its accommodation. We are to be expelled without any previous consultation from the rooms that were built for us and which we have occupied for eighty years; and now government proposes to put us into a miserably inconvenient house in a bad situation and to give for our installation a sum which at the highest computation is less than half of what is necessary. The only compensation being a shadowy promise to remedy another grievance of thirty years standing by giving us a publication grant of £300.

Chrystal was the main force behind the success in finding new accommodation for the Society. The Treasury granted £25,000 for the purchase of 22-24 George Street in Edinburgh, and £3,000 to cover the cost of removal and equipment. The Society still occupies this accommodation in George Street, but has recently purchased the adjacent property which will soon become part of the premises.

The Royal Society of Edinburgh was not the only Edinburgh Society with which Chrystal was closely connected. His interest and support in setting up the Edinburgh Mathematical Society was important in the foundation of this Society. The first regular meeting was held on 12 March 1883, and Chrystal had the honour of giving the first introductory address, the subject of which was Present Fields of Mathematical Research. Tait and Chrystal were the first two Honorary members elected by the Society and as Honorary members, they were not eligible to serve as officers of the Society.

Another area in which Chrystal's influence was far reaching was in the reforms in Scottish school education. In 1885 Chrystal, along with some other university professors, was invited to make inspections of secondary schools, and as a result the idea of a Leaving Certificate Examination occurred to him. This was immediately taken up, and was implemented by the Scottish Education Department. After initial problems, recognition from universities and other professional bodies in the country put the new examination on a sound footing and it survives in modified form to this day.

Chrystal's mathematical publications cover many topics including non-euclidean geometry, line geometry, determinants, conics, optics, differential equations, and partitions of numbers. However, his most famous publication is without doubt his book Algebra. He said [7]:-

For our teaching of algebra, I am afraid we can claim neither the sanction of antiquity nor the light of modern times. Whether we look at the elementary, or what is called the higher teaching of this subject the result is unsatisfactory. In the higher teaching which interests me most, I have to complain of the utter neglect of all important notion of algebraic form.

The logic of the subject, which, both educationally and scientifically speaking, is the most important part of it, is wholly neglected. The whole training consists in example grinding. What should have been the help to attain the end has become the end itself. The result is that algebra, as we teach it, is neither an art nor a science, but an ill-farrago of rules; whose object is the solution of examination problems.

The first volume of the book, entitled Algebra : An Elementary Textbook for the Higher Classes of Secondary Schools and for Colleges was published in 1886. He continued his project producing the second volume in November 1889. A review which appeared in the Athenaeum comments:-

It is the completest work on Algebra that has yet come before us, and in lucidity of exposition it is second to none. The author views his subject from the high ground of the educationist, without reference to the exigencies of established examinations; yet neither the candidates who are training for such nor the teachers who prepare them will act wisely if they neglect his lessons.

Another review in the Academy states:-

The explanations are admirably clear, and the arrangement appears to be a very good one. No teacher of the high classes in our schools or of students preparing for the university examinations should be without this book. There is nothing like it in English, and it forms an excellent introduction to the various applications of Algebra to the higher analysis.

The last few years of Chrystal's life were devoted to a different research topic from anything he had studied up to that point. In February 1903 he was asked to give a brief account of the hydrodynamical principles of seiches, with suggestions to surveyors regarding the observations they might make on Scottish lakes in the Scottish Lake Survey. Seiches are oscillations in the water level occurring in lakes and along sea coasts. Chrystal published three major papers on the subject in 1904, 1905 and 1906 which were all published by the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

In these and subsequent papers Chrystal studied seiches in lakes of many different shapes. He also revived his interest in carrying out experiments and in 1905 he organised an investigation of the seiches of Loch Earn, also making observations for comparison on Lochs Tay and Lubnaig. He supervised the whole of the work and designed special instruments to carry out the measurements.

Recognition for his work on seiches came through the Gunning Victoria Award made to him by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, one of the most prestigious awards of the Society, and the Royal Medal by the Royal Society of London, confirmation of which came from the King just two hours after his death.

It is interesting to look at some descriptions of Chrystal's character. In [2] he is described as follows:-

He was a strong personality, and as a teacher he was kindly and sympathetic.

In [26] he is described by the Edinburgh students of 1890:-

As a professor in his own class-room, no one could be more courteous and considerate than Professor Chrystal. He grudges neither time nor labour in the elucidation of the numerous difficulties of his students. The gulf which is said to be fixed between professors and students cannot be said to have existence in the mathematical class-room. Professor Chrystal is perhaps the most approachable of all our professors.

The students of Edinburgh described the ageing Chrystal in 1907 [27]:-

...our clearest recollection of Professor Chrystal stands out from a mist of dingy lecture-rooms in the old buildings. It consists of a grey-headed but erect figure, dashing, with marvellous speed, cohorts and battalions of graphs, theorems, triangles, and symbols upon a silent, but secretly suffering black-board. Then, when every available square inch of space had been filled, there was a triumphant swing round to his astounded audience, as the professor sped on to some other colossal piece of mathematical architecture.

We recall the voice, convincing and sustained, soaring intrepidly through a mass of stupefying calculation. We recall the genial face, flushed with a victorious effort over the obstinate powers of x and y, the glasses twinkling with the success of a clear piece of demonstration. ... A strong personality is his. There are few classes so completely dominated by their teachers as Professor Chrystal's; he has a fine and tactful sarcasm which he knows well how to use ... .

But those who only know the Chrystal of the class-room know little of him. There is the Chrystal of the private interview - a kindly, sympathetic, helpful teacher. There is the Chrystal who, as Dean of the Faculty of Arts, advises the timid urchin hesitating on the threshold of his academic career, or guides the inexperienced footsteps of students as they face out into the unknown world. And there are many who owe to him more than they themselves are aware of.

http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Obits/Chrystal.html]

Articles:

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي للقرآن الكريم يقيم جلسة حوارية لطلبة جامعة الكوفة

|

|

|