تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

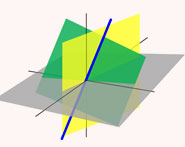

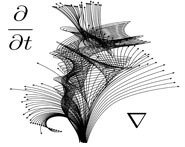

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 14-7-2016

Date: 21-7-2016

Date: 13-7-2016

|

Born: 16 March 1789 in Erlangen, Bavaria (now Germany)

Died: 6 July 1854 in Munich, Bavaria, Germany

Georg Simon Ohm came from a Protestant family. His father, Johann Wolfgang Ohm, was a locksmith while his mother, Maria Elizabeth Beck, was the daughter of a tailor. Although his parents had not been formally educated, Ohm's father was a rather remarkable man who had educated himself to a high level and was able to give his sons an excellent education through his own teachings. Had Ohm's brothers and sisters all survived he would have been one of a large family but, as was common in those times, several of the children died in their childhood. Of the seven children born to Johann and Maria Ohm only three survived, Georg Simon, his brother Martin who went on to become a well-known mathematician, and his sister Elizabeth Barbara.

When they were children, Georg Simon and Martin were taught by their father who brought them to a high standard in mathematics, physics, chemistry and philosophy. This was in stark contrast to their school education. Georg Simon entered Erlangen Gymnasium at the age of eleven but there he received little in the way of scientific training. In fact this formal part of his schooling was uninspired stressing learning by rote and interpreting texts. This contrasted strongly with the inspired instruction that both Georg Simon and Martin received from their father who brought them to a level in mathematics which led the professor at the University of Erlangen, Karl Christian von Langsdorf, to compare them to the Bernoulli family. It is worth stressing again the remarkable achievement of Johann Wolfgang Ohm, an entirely self-taught man, to have been able to give his sons such a fine mathematical and scientific education.

In 1805 Ohm entered the University of Erlangen but he became rather carried away with student life. Rather than concentrate on his studies he spent much time dancing, ice skating and playing billiards. Ohm's father, angry that his son was wasting the educational opportunity that he himself had never been fortunate enough to experience, demanded that Ohm leave the university after three semesters. Ohm went (or more accurately, was sent) to Switzerland where, in September 1806, he took up a post as a mathematics teacher in a school in Gottstadt bei Nydau.

Karl Christian von Langsdorf left the University of Erlangen in early 1809 to take up a post in the University of Heidelberg and Ohm would have liked to have gone with him to Heidelberg to restart his mathematical studies. Langsdorf, however, advised Ohm to continue with his studies of mathematics on his own, advising Ohm to read the works of Euler, Laplace and Lacroix. Rather reluctantly Ohm took his advice but he left his teaching post in Gottstadt bei Nydau in March 1809 to become a private tutor in Neuchâtel. For two years he carried out his duties as a tutor while he followed Langsdorf's advice and continued his private study of mathematics. Then in April 1811 he returned to the University of Erlangen.

His private studies had stood him in good stead for he received a doctorate from Erlangen on 25 October 1811 and immediately joined the staff as a mathematics lecturer. After three semesters Ohm gave up his university post. He could not see how he could attain a better status at Erlangen as prospects there were poor while he essentially lived in poverty in the lecturing post. The Bavarian government offered him a post as a teacher of mathematics and physics at a poor quality school in Bamberg and he took up the post there in January 1813.

This was not the successful career envisaged by Ohm and he decided that he would have to show that he was worth much more than a teacher in a poor school. He worked on writing an elementary book on the teaching of geometry while remaining desperately unhappy in his job. After Ohm had endured the school for three years it was closed down in February 1816. The Bavarian government then sent him to an overcrowded school in Bamberg to help out with the mathematics teaching.

On 11 September 1817 Ohm received an offer of the post of teacher of mathematics and physics at the Jesuit Gymnasium of Cologne. This was a better school than any that Ohm had taught in previously and it had a well equipped physics laboratory. As he had done for so much of his life, Ohm continued his private studies reading the texts of the leading French mathematicians Lagrange, Legendre, Laplace, Biot and Poisson. He moved on to reading the works of Fourier and Fresnel and he began his own experimental work in the school physics laboratory after he had learnt of Oersted's discovery of electromagnetism in 1820. At first his experiments were conducted for his own educational benefit as were the private studies he made of the works of the leading mathematicians.

The Jesuit Gymnasium of Cologne failed to continue to keep up the high standards that it had when Ohm began to work there so, by 1825, he decided that he would try again to attain the job he really wanted, namely a post in a university. Realising that the way into such a post would have to be through research publications, he changed his attitude towards the experimental work he was undertaking and began to systematically work towards the publication of his results [1]:-

Overburdened with students, finding little appreciation for his conscientious efforts, and realising that he would never marry, he turned to science both to prove himself to the world and to have something solid on which to base his petition for a position in a more stimulating environment.

In fact he had already convinced himself of the truth of what we call today "Ohm's law" namely the relationship that the current through most materials is directly proportional to the potential difference applied across the material. The result was not contained in Ohm's firsts paper published in 1825, however, for this paper examines the decrease in the electromagnetic force produced by a wire as the length of the wire increased. The paper deduced mathematical relationships based purely on the experimental evidence that Ohm had tabulated.

In two important papers in 1826, Ohm gave a mathematical description of conduction in circuits modelled on Fourier's study of heat conduction. These papers continue Ohm's deduction of results from experimental evidence and, particularly in the second, he was able to propose laws which went a long way to explaining results of others working on galvanic electricity. The second paper certainly is the first step in a comprehensive theory which Ohm was able to give in his famous book published in the following year.

What is now known as Ohm's law appears in this famous book Die galvanische Kette, mathematisch bearbeitet (1827) in which he gave his complete theory of electricity. The book begins with the mathematical background necessary for an understanding of the rest of the work. We should remark here that such a mathematical background was necessary for even the leading German physicists to understand the work, for the emphasis at this time was on a non-mathematical approach to physics. We should also remark that, despite Ohm's attempts in this introduction, he was not really successful in convincing the older German physicists that the mathematical approach was the right one. To some extent, as Caneva explains in [1], this was Ohm's own fault:-

... in neither the introduction nor the body of the work, which contained the more rigorous development of the theory, did Ohm bring decisively home either the underlying unity of the whole or the connections between fundamental assumptions and major deductions. For example, although his theory was conceived as a strict deductive system based on three fundamental laws, he nowhere indicated precisely which of their several mathematical and verbal expressions he wished to be taken as the canonical form.

It is interesting that Ohm's presents his theory as one of contiguous action, a theory which opposed the concept of action at a distance. Ohm believed that the communication of electricity occurred between "contiguous particles" which is the term Ohm himself uses. The paper [8] is concerned with this idea, and in particular with illustrating the differences in scientific approach between Ohm and that of Fourier and Navier. A detailed study of the conceptual framework used by Ohm in formulating Ohm's law is given in [6].

As we described above, Ohm was at the Jesuit Gymnasium of Cologne when he began his important publications in 1825. He was given a year off work in which to concentrate on his research beginning in August 1826 and although he only received the less than generous offer of half pay, he was able to spend the year in Berlin working on his publications. Ohm had believed that his publications would lead to his receiving an offer of a university post before having to return to Cologne but by the time he was due to begin teaching again in September 1827 he was still without such an offer.

Although Ohm's work strongly influenced theory, it was received with little enthusiasm. Ohm's feeling were hurt, he decided to remain in Berlin and, in March 1828, he formally resigned his position at Cologne. He took some temporary work teaching mathematics in schools in Berlin.

He accepted a position at Nüremberg in 1833 and although this gave him the title of professor, it was still not the university post for which he had strived all his life. His work was eventually recognised by the Royal Society with its award of the Copley Medal in 1841. He became a foreign member of the Royal Society in 1842. Other academies such as those in Berlin and Turin elected him a corresponding member, and in 1845 he became a full member of the Bavarian Academy.

This belated recognition was welcome but there remains the question of why someone who today is a household name for his important contribution struggled for so long to gain acknowledgement. This may have no simple explanation but rather be the result of a number of different contributary factors. One factor may have been the inwardness of Ohm's character while another was certainly his mathematical approach to topics which at that time were studied in his country a non-mathematical way. There was undoubtedly also personal disputes with the men in power which did Ohm no good at all. He certainly did not find favour with Johannes Schultz who was an influential figure in the ministry of education in Berlin, and with Georg Friedrich Pohl, a professor of physics in that city.

Electricity was not the only topic on which Ohm undertook research, and not the only topic in which he ended up in controversy. In 1843 he stated the fundamental principle of physiological acoustics, concerned with the way in which one hears combination tones. However the assumptions which he made in his mathematical derivation were not totally justified and this resulted in a bitter dispute with the physicist August Seebeck. He succeeded in discrediting Ohm's hypothesis and Ohm had to acknowledge his error. See [10] for details of the dispute between Ohm and Seebeck.

In 1849 Ohm took up a post in Munich as curator of the Bavarian Academy's physical cabinet and began to lecture at the University of Munich. Only in 1852, two years before his death, did Ohm achieve his lifelong ambition of being appointed to the chair of physics at the University of Munich.

1. K L Caneva, Biography in Dictionary of Scientific Biography (New York 1970-1990).

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2830903216.html

2. Biography in Encyclopaedia Britannica.

http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9056864/Georg-Simon-Ohm

Books:

3. E Deuerlein, Georg Simon Ohm, 1789-1854 (Erlangen, 1939).

4. C Jungnickel and R McCormmach, Intellectual Mastery of Nature : Theoretical physics from Ohm to Einstein, 2 Volumes (Chicago, 1986).

5. H von Füchtbauer, Georg Simon Ohm. Ein Forscher wächst aus seiner Väter Art (Berlin, 1939).

Articles:

6. T Archibald, Tension and potential from Ohm to Kirchhoff, Centaurus 31 (2) (1988), 141-163.

7. G Baker, Georg Simon Ohm, Short wave magazine 52 (1953), 41.

8. B Pourprix, G S Ohm théoricien de l'action contigue, Arch. Internat. Hist. Sci. 45 (134) (1995), 30-56.

9. B Pourprix, La mathématisation des phénomènes galvaniques par G S Ohm (1825-1827), La mathématisation 1780-1830, Rev. Histoire Sci. 42 (1-2) (1989), 139-154.

10. R S Turner, The Ohm-Seebeck dispute, Hermann von Helmholtz, and the origins of physiological acoustics, British J. Hist. Sci. 10 (34) (1) (1977), 1-24.

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تستعد لإطلاق الحفل المركزي لتخرج طلبة الجامعات العراقية

|

|

|