النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 9-12-2015

Date: 23-2-2021

Date: 9-12-2020

|

Clathrin

Clathrin is the major component of purified coated vesicles (1), intracellular structures that derive from coated membrane involved in endocytosis and receptor recycling.

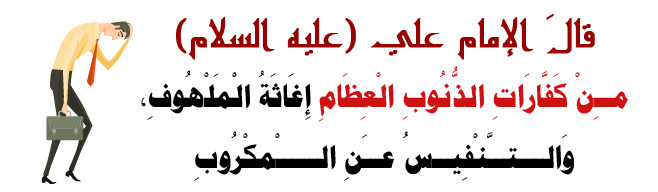

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (2, 3) is the major route for the uptake of specific macromolecules into cells for example, low density lipoprotein carrying cholesterol and transferrin bearing iron. Such macromolecules are concentrated from the surrounding cellular fluid by binding to the receptors exposed on the surface of cells. The receptors, in turn, have features in their cytoplasmic tails that enable them to cluster into clathrin-coated pits and thus be endocytosed efficiently in small vesicles. (Fig. 1). The vesicles, in addition, carry other molecules that target them to an internal compartment, the endosome, and allow them to fuse with the endosomal membrane, thus delivering the cargo of nutrients into the lumen for use by the cell. Meanwhile, the coat proteins and receptors are recycled through the endosomal compartment and back to the plasma membrane. The coat proteins diffuse through the cytoplasm to reform coated pits there for a further round of endocytosis.

Figure 1. Endocytosis promoted by a round of clathrin assembly and recycling. Cytoplasmic clathrin triskelions and adaptors (containing specific 100 kDa adaptins and associated subunits) are triggered to assemble on the membrane in a reaction involving GTP-binding proteins with a selection of receptors to form a coated pit(2). The coated pit invaginates as further receptors and coat proteins assemble(3). Pinching-off the completed coated vesicle(4) requires dynamin to promote fusion in the neck region. Uncoating follows, releasing the vesicle (5), which carries molecules primed for fusion with the endosome(6), and the soluble coat components, which recycle(1).

This system of budding coated vesicles is used again and again throughout cellular biology. Thus clathrin-coated vesicles are involved in antigen presentation in immunology (4) in delivering receptors and signaling molecules at the right place and time during development (5) and in recycling synaptic vesicle components in nerve synapses (6). In essence, clathrin and its associated proteins provide a mechanism for efficient recycling of specific receptors that are controlled in various ways. Other non-clathrin coated vesicle systems that contain a spectrum of related molecules and certain quite distinct coat components mediate sorting and recycling steps throughout the secretory pathway (7, 8). Clathrin-coated vesicles are more particularly associated with sorting specific molecules from the trans Golgi network into the pre-lysosomal/endosome network in addition to their endocytic function.

Unfortunately, viruses [eg, influenza virus (9)] exploit the endocytic system to infect cells, and various other pathogens and foreign substances do damage to cells by this route. Defects in the system are also the root cause of certain medical conditions, for example, familial hypercholesterolaemia (2), and I-cell disease (10).

1. Clathrin

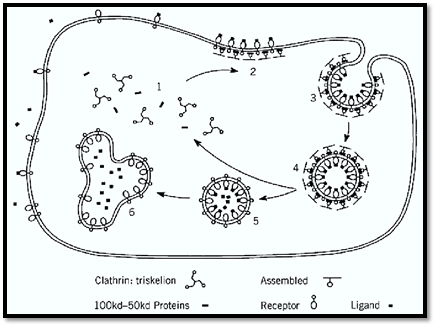

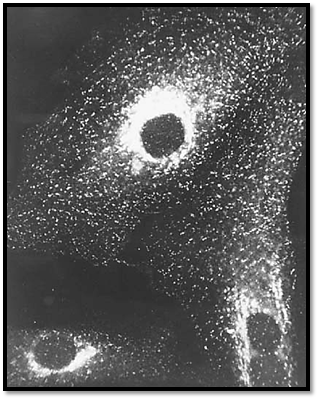

The function of clathrin is to form the strong outer, or cytoplasmic, surface of the coat, a remarkable honeycomb of hexagons and pentagons (Fig. 2). This flexible, structural network accommodates extensive areas of flattish membrane or encloses a range of vesicles, the smallest of which (250 Å diameter) is contained within a truncated icosahedron composed of 20 hexagons and 12 pentagons .

Figure 2. Field of unstained placental coated vesicles in ice. Hexagonal barrels (H), tennis ball structures (T), larger coats containing vesicle (V), and ferritin (F) are indicated. Scale bar 200 nm.

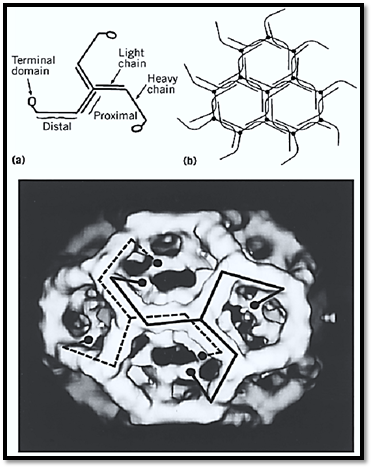

The modular design of the clathrin molecule is extraordinary and unexpected [Fig. 3(a)]. The overall shape is that of a triskelion (12, 13). Three heavy chains (180 kDa) and three light chains (one LCa and 2 LCb) form the three-legged structure. The C-termini of the heavy chains come together to form the hub of the structure, and the N-termini are in the terminal domains of the extended legs. The light chains are located along the proximal leg regions, possibly contributing in some way to the geometry at the vertex. Beyond the light chains, the heavy chains exhibit a kink, and the distal ends bend yet again to form a more globular terminal domain.

Figure 3. (a) Schematic drawing showing the modular structure of the triskelion. (b) Packing diagram showing how triskelions (lacking terminal domains for simplicity) form a hexagonal lattice. (c) Three-dimensional map of a clathrin cage containing 12 pentagons and 8 hexagons, computed from electron micrographs of unstained specimens embedded in vitreous ice. Each triskelion leg runs from one vertex along two neighboring polygonal edges and then turns inward. Its terminal domain forms the inner shell of density.

The packing arrangement of the triskelions (lacking terminal domains for simplicity) to form a hexagonal lattice is shown in Fig. 3(b). The profiles of two complete triskelions are shown at adjacent vertices of a clathrin cage in the form of a hexagonal barrel in Fig. 3(c).

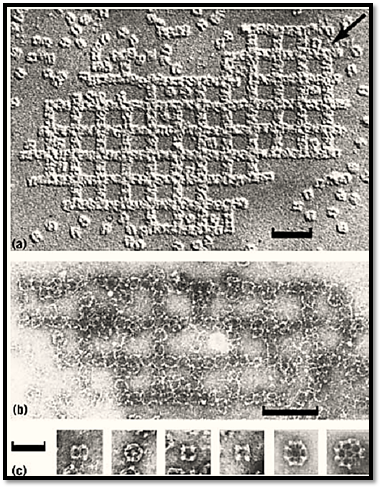

In vitro in artificial conditions, clathrin exhibits its versatility as a construction molecule (Fig. 4). Among other small particles, clathrin makes cubes [Fig. 4(c)] a variant of the normal cage (14). In turn the cubes pack together to form remarkable arrays that resemble the foundations of buildings [Fig. 4(a) and (b)].

Figure 4. The most astonishing type of clathrin aggregate produced in vitro is an open square packing of cubes in a pattern reminiscent of the foundations of an ancient building visualized by (a) unidirectional shadowing; (b) negative staining in uranyl acetate (bar 0.2 µm); (c) comparison of cubes with cages, showing from left to right, two-fold, three-fold, and two four-fold views of the cube plus cages of the hexagonal barrel and truncated icosahedron type (football.( The edge of the cube is more than twice as long as the vertex to vertex distance in the cages. Bar, 0.1 µm.

cDNAs coding for clathrin heavy chains and light chains have been cloned and sequenced (15, 16). The sequences suggest that part of the light chains form a coiled-coil structure with a corresponding part of the heavy chain to form the proximal legs. Extensive studies of the interaction between light chains and heavy chains, using antibodies and mutational analysis, have provided further evidence for the positioning of the light chains along the proximal leg, studies also indicate that the C-termini of the light chains occur at the vertex, where they might influence the structural angles involved in cage assembly. Now the prospects are good for obtaining crystals suitable for determining the high-resolution structure by X-ray crystallography from material produced by expressing parts of the triskelion (e.g., the hub region) in E. coli (17).

An interesting problem is how spurious clathrin cage formation is prevented in the cytoplasm or indeed how clathrin triskelions are disassembled from the coat structure after vesicle budding but are not prevented from forming coated pits. Recently, other attendant “chaperone” proteins, hsp70c and cofactor auxilin, have been found, which modulate cage assembly in the cytoplasm (18.(

Cloning of clathrin genes has also led to further exploration of the role of clathrin by gene knockout and mutation. Deletion of the clathrin gene in yeast makes various strains very sick, slow growing, or dead. In those that survive, membrane organization is affected. In particular, the processing of pre-pro-a-factor by the kex2 endoproteinase is disrupted, leading to secretion of the immature a-factor and failure in sexual reproduction, and endocytosis of specific molecules, for example, kex2, is reduced, and the cells fill with abnormal vacuoles (19). In a temperature-sensitive mutant of clathrin, transient defects have been observed in sorting to the vacuole. The picture emerging (20) is not dissimilar to that observed in mammalian cells, that is, clathrin is involved in specific sorting steps both in the trans Golgi region and during endocytosis at the plasma membrane. These are the sites where the characteristic coated structures, now confirmed as clathrin-coated pits, were seen in abundance in early electron microscope pictures of fixed cell sections (21, 22). In a more complex creature, the slime mold, Dictyostelium discoideum (23), failure of clathrin heavy chain expression in cells impairs endocytosis and causes a lack of endosomes and contractile vacuoles, leading to defects in osmoregulation. Such cells also cannot follow the developmental program.

In Drosophila melanogaster, the clathrin heavy chain gene is essential (24). However, in flies, a dramatic effect is caused by the shibire mutation. This is a temperature-sensitive mutation in the molecule, now known to be dynamin, that is required for budding off a clathrin-coated vesicle (25, 26 ) . At the nonpermissive temperature, the flies drop down as if dead. They cannot recycle their synaptic vesicle components in synapses and therefore cease to fly. However, when cooled down again, they start to fly as usual. These results confirm and extend the original electron microscope observations of abundant clathrin-coated vesicles in nerve synapses (27) and particularly the neuromuscular junction (28). Recent studies have identified many more components in the synaptic vesicle cycle (6) and explored their role by genetic manipulation in Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans [see Fig. 1; (29-32)].

In the worm, C. elegans, clathrin-mediated sorting has been implicated in the development of the vulval region (5). This study suggests that even apparently quite subtle perturbations in sorting by the coated vesicle system have profound effects in the development of a complex organism.

Recently, a second clathrin heavy-chain gene (CLTD) has been identified in humans, which has its maximal level of expression in skeletal muscle (33). This gene was found in the region commonly deleted in velo-cardio-facial syndrome (VCFS). Based on the location and expression pattern of CLTD, the suggestion is that hemizygosity at this locus plays a role in the etiology of one of the VCFS-associated phenotypes.

In summary, the clathrin molecule is an extraordinary building unit that has an intricate packing arrangement and forms coated structures of striking beauty. It carries out an important function.

The assembly properties of clathrin with the coated structures and vesicles it encloses have allowed purifying and identifying many of the other functional components involved. Chief among these are the clathrin adaptors, heterotetrameric complexes that coassemble with clathrin to form the vesicle coat.

-Clathrin Adaptors

Two distinct types of clathrin adaptor complexes have been identified (3, 34). One of these (the PM-adaptor) consists of an a-adaptin (~100 kDa) combined with b-adaptin (~100 kDa) and two smaller subunits, AP50 and AP17. This adaptor is found by immunofluorescence with a monoclonal antibody against a-adaptin mainly in plasma-membrane-coated pits. In contrast, the second, the Golgi adaptor, consists of g-adaptin (~95 kDa) combined with b′-adaptin and two other subunits, AP47 and AP20, and is found by immunofluorescence using a monoclonal antibody against g-adaptin in coated pits in the trans Golgi network (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Immunofluorescence localization of clathrin in fibroblasts showing coated pits on the plasma membrane and in Robinson and B.M.F. Pearse (1986) J. Cell Biol. 102, 48–54.]

References

1. B. M. F. Pearse (1975) J. Mol. Biol. 97, 93–98.

2. J. L. Goldstein, M. S. Brown, R. G. W. Anderson, D. W. Russell, and W. J. Schneider (1985) An

3. B. M. F. Pearse and M. S. Robinson (1990) Ann. Rev. Cell Biol. 6, 151–171.

4. P. R. Wolf and H. L. Ploegh (1995) Ann. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 267–306.

5.J. Lee, G. D. Jongeward, and P. W. Sternberg (1994) Genes Dev. 8, 60–73.

6. P. R. Maycox, E. Link, A. Reetz, S. A. Morris, and R. Jahn (1992) J. Cell Biol. 118, 1379–1388.

7. R. Schekman and L. Orci (1996) Science 271, 1526–1533.

8. J. E. Rothman and F. T. Wieland (1996) Science 272, 227–234.

9. T. Stegmann, R. W. Doms, and A. Helenius (1989) Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 18, 187

10. S. Kornfeld (1986) J. Clin. Invest. 77, 1–6.

11. B. M. F. Pearse and R. A. Crowther (1987) Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 16, 49–68.

12. E. Ungewickell and D. Branton (1981) Nature 289, 420–422.

13. T. Kirchhausen and S. C. Harrison (1981) Cell 23, 755–761.

14. P. K. Sorger, R. A. Crowther, J. T. Finch, and B. M. F. Pearse (1986) J. Cell Biol. 103, 1213–12

15. A. P. Jackson, H. Seow, N. Holmes, K. Drickamer, and P. Parham (1987) Nature 326, 154–159.

16. T. Kirchhausen, S. C. Harrison, E. Ping Chow, R. J. Mattaliano, K. L. Ramachandran, J. Smart, Acad. Sci. USA 84, 8805–8809.

17. S. Liu, M. Wong, C. S. Craik, and F. M. Brodsky (1995) Cell 83, 257–267.

18. E. Ungewickell, H. Ungewickell, S. E. H. Holstein, R. Lindner, K. Prasad, W. Barouch, B. Mart (1995) Nature 378, 632–635.

19. G. S. Payne and R. Schekman (1989) Science 245, 1358–1365.

20. E. Conibear and T. H. Stevens (1995) Cell 83, 513–516.

21. T. F. Roth and K. R. Porter (1964) J. Cell Biol. 20, 313–332.

22. D. S. Friend and M.G. Farquhar (1967) J. Cell Biol. 35, 357–376.

23. T. J. O''Halloran and R. G. W. Anderson (1992) J. Cell Biol. 118, 1371–1377.

24. C. Bazinet, A. L. Katzen, M. Morgan, A. P. Mahowald, and S. K. Lemmon (1993) Genetics 134

25. T. Kosaka and K. Ikeda (1983) J. Cell Biol. 97, 499–507.

26. H. Damke, T. Baba, A. M. van der Bliek, and S. L. Schmid (1995) J. Cell Biol. 131, 69–80.

27. E. G. Gray and R. A. Willis (1970) Brain Res. 24, 149–168.

28. J. E. Heuser and T. S. Reese (1973) J. Cell Biol. 57, 315–344.

29. A. DiAntonio and T. L. Schwarz (1994) Neuron 12, 909–920.

30. K. Broadie, A. Prokop, H. J. Bellen, C. J. O''Kane, K. L. Schulze, and S. T. Sweeney (1995) Neu

31. Y. Fujita, T. Sasaki, K. Fukui, H. Kotani, T. Kimura, Y. Hata, T. C. Sudhof, R. H. Scheller, and 271, 7265–7268.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|