Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-01-20

Date: 8-3-2022

Date: 2024-01-12

|

Syntax Word order and semantic type

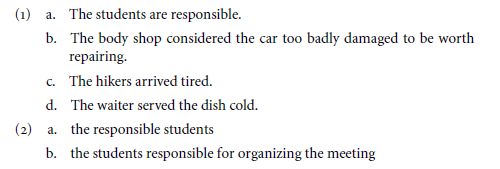

In English and other languages with a productive category of adjectives, APs have perhaps the most varied distribution of any syntactic category. They can serve not only as primary or secondary predicates (the former, typically in conjunction with a copular verb; the latter, as arguments or adjuncts), as in (1), but also as modifiers of nominals, as in (2).1 No other syntactic category manifests this degree of flexibility.

Early formal semantic analyses of adjectives treated the category as ambiguous (see e.g. Siegel 1976 and the discussion in Dowty et al., 1981; note that there are differences of detail between the analyses in these works and the sketch presented here. Some adjectives were analyzed as properties of individuals (type (e, t,) limiting ourselves to extensional types); this is particularly natural for those with predicative uses or strictly intersective interpretations.2 Others, such as former, which lacks a predicative use (see (3b)), were taken to denote exclusively properties of properties (type (e, t), (e, t)).

In fact, Siegel proposed that the vast majority of adjectives were ambiguous between these two types. One argument for doing so is the variation between intersective and non-intersective interpretations that many adjectives manifest. For example, old job does not denote the intersection of jobs and old things (cf. (4b) and the parallel examples involving car).

Another argument (see Dowty et al. 1981) for assigning as many adjectives as possible to the predicate modifier type, perhaps alongside a predicative type, is that doing so permits a uniform compositional semantic rule for AP–noun combinations – a generalization to the worst case that assimilates all adjectives to those like former and avoids having to postulate distinct rules for the semantic composition of (e, t) and (e, t), (e, t)-type adjectives with nominals.3

However, Larson (1998) provides a series of arguments against this double type assignment for adjectives and in favor of analyzing as many adjectives as possible – even some ostensibly non-predicative ones such as occasional – exclusively as properties of individuals or events. It remains to be seen whether all adjectives can be profitably reanalyzed intersectively, but see Landman (2001) and McNally and Boleda (2004) for recent efforts in this direction. It may seem that Larson’s effort to reduce complexity in the lexicon comes at the price of introducing greater complexity in the compositional system and syntax–semantics interface, as somewhat more elaborate compositional rules will be necessary to produce apparently non-intersective readings for most adjectives. However, that complexity might be necessary anyway: one compelling argument for positing two composition operations for AP–noun combinations is the fact that only APs that have predicative uses are systematically licensed as postnominal modifiers in English and the Romance languages (see e.g. the Spanish examples in (6)), suggesting that noun–AP structures can only be semantically composed via intersection.4

As suggested earlier, an idiosyncratic intersective composition rule seems like a rather glaring exception to the general possibility of type-driven composition in natural language. Is there anything that can be done to make sense out of this exception, or even to analyze it away? Though this question remains to be answered, the beginning of an answer is suggested in the sort of proposal advocated by Richard Larson and Hiroko Yamakido in this volume.

As Larson and Yamakido point out, in the Montague semantic tradition, determiners are effectively treated as heads that take nouns or other property type expressions as their arguments. Larson and Yamakido point to the existence of various kinds of special morphology on adjectives, including the Ezafe construction in Persian and determiner spreading in Modern Greek, which might be insightfully analyzed if we treat adjectives as Case-marked arguments of a determiner functor. Intriguingly, this sort of morphology only occurs on intersective adjectives. If not only the noun but also (at least in some cases) accompanying intersective adjectives in a noun phrase can be treated as arguments of the determiner, we might be able to recast what appears to be an idiosyncratic intersection of AP and noun denotations as the product of type-driven composition whose semantic details are a natural product of the semantics of the determiner.

If we limit our attention to just prenominal or postnominal position (depending on the language in question), a second puzzle quickly becomes evident: when a string of APs appear together, their order is not random, as the following examples show. In both cases, in the absence of any context the (a) examples sound much more natural than the (b) examples. We might call this problem the “stacking” problem.

The oddness of certain adjective orderings would not be surprising if the adjectives in question were not intersective, since in such cases different orders could yield different interpretations due to resulting differences in the relative scopes of the adjectives. Intersective adjectives such as those in (7) and (8), however, should not give rise to such scope differences, and thus there should be no a priori reason to prefer one adjective ordering to another, or to prefer any particular ordering of adjectives with respect to other intersective modifiers such as numerals within the nominal.5 Facts like these have led descriptive grammars such as Quirk et al. (1985) to propose ordering hierarchies on DP-internal adjectives, which works such as Cinque (1994) and Scott (2002) have attempted to formalize via a highly articulated syntactic structure that makes reference to semantic categories as detailed as size and color. However, the viability of such a detailed structure is questioned by Bouchard (2005) and Svenonius (this volume). Bouchard, in a study of adjective ordering in French, suggests that the only ordering that can be imposed is one on which adjectives that serve to create sortal subcategories (e.g. Mediterranean in Mediterranean diet) appear closer to the head noun than those which simply add ancillary descriptive content. The facts discussed in the chapter by Svenonius suggest that the truth is somewhere in between: the constraints on adjective ordering might be more rigid than Bouchard would suggest, but less rigid than those fixed by the Quirk-type hierarchy or Cinque’s or Scott’s analyses.

Though the stacking problem does not arise with adverbs or AdvPs in the same way as it does with APs, adverbs certainly raise questions concerning the relation between word order and semantic type (see Jackendoff 1972, Wyner, this volume, and the many works cited in the latter). For example, manner adverbs have been classically treated as verb phrase modifiers and assigned a corresponding semantics (such as a property of events denotation), while so-called “speaker-oriented” adverbs like fortunately have been analyzed as sentence modifiers that denote properties of propositions. Such proposals account for the oddness out of context of e.g. (9b) in comparison to (9a).

However, in fact adverbs do not have such a neat distribution: it is neither so restricted as analyses such as Jackendoff’s would predict, though perhaps nor so free as might be expected by the kind of alternative proposed in Adam Wyne’s contribution to this volume. The situation is thus reminiscent of the stacking problem for adjectives, but it remains to be explored to what extent the account for the one will extend to the other.

1 We use the term “modifier” here as a convenient label for uses of APs inside nominal expressions, without any commitment as to how those APs or nominals should be analyzed.

2 A modifier is generally defined as intersective if the denotation of the modifier + modified is identical to the intersection of the set of individuals described by the modifier with the set described by the modified expression.

3 For the former case, a special composition rule for the nominal would be needed which intersects the AP and noun denotations; for the latter, a typical functor-argument application rule.

4 Of course, in English many APs do not function well as postnominal modifiers unless they are syntactically complex or modify a quantificational pronoun such as everyone:

(i) ∗The kids tired can take a rest.

(ii) The kids tired of playing soccer can take a rest.

(iii) Everyone tired can take a rest.

But this simply means that being potentially predicative is only a necessary and not a sufficient condition for appearing in postnominal position. See Larson and Yamakido, this volume, and references cited there.

5 In fact, precisely the absence of scope interactions has been one of the arguments for treating adverbial phrases as intersective predicates of events.

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي يقيم ورشة تطويرية ودورة قرآنية في النجف والديوانية

|

|

|