النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Genomics and Bacterial Pathogenicity

المؤلف:

Carroll, K. C., Hobden, J. A., Miller, S., Morse, S. A., Mietzner, T. A., Detrick, B

المصدر:

Jawetz, Melnick, & Adelberg’s Medical Microbiology

الجزء والصفحة:

27E , P156-157

2025-02-24

1095

Bacteria are haploid and limit genetic interactions that might change their chromosomes and potentially disrupt their adaptation and survival in specific environmental niches. One important result of the conservation of chromosomal genes in bacteria is that the organisms are clonal. For many pathogens, there are only one or a few clonal types that are spread in the world during a period of time. For example, epidemic serogroup A meningococcal meningitis occurs in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa and occasionally spreads into Northern Europe and the Americas. On several occasions, over a period of decades, single clonal types of serogroup A Neisseria meningitidis have been observed to appear in one geographic area and subsequently spread to others with resultant epidemic disease. There are two clonal types of Bordetella pertussis, both associated with disease. There are, however, mechanisms that bacteria use, or have used a long time in the past, to transmit virulence genes from one to another.

Mobile Genetic Elements

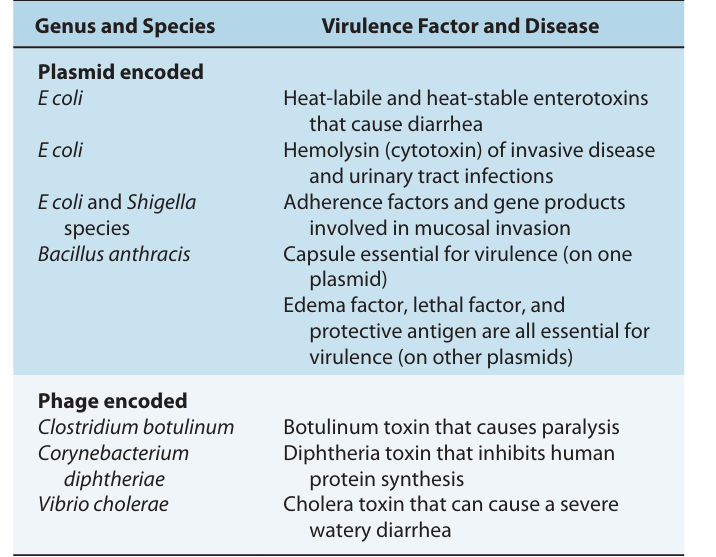

Primary mechanisms for exchange of genetic information between bacteria include natural transformation and transmissible mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, transposons, and bacteriophages (often referred to as “phages”). Transformation occurs when DNA from one organism is released into the environment and is taken up by a different organism that is capable of recognizing and binding DNA. In other cases, the genes that encode many bacterial virulence factors are carried on plasmids, transposons, or phages. Plasmids are extrachromosomal pieces of DNA and are capable of replicating. Transposons are highly mobile segments of DNA that can move from one part of the DNA to another. This can result in recombination between extrachromosomal DNA and the chromosome. If this recombination occurs, the genes coding for virulence factors may become chromosomal. Finally, bacterial viruses or phages are another mechanism by which DNA can be moved from one organism to another. Transfer of these mobile genetic elements between members of one species or, less commonly, between species can result in transfer of virulence factors, including antimicrobial resistance genes. A few examples of plasmid- and phage-encoded virulence factors are given in Table 1.

Table1. Examples of Virulence Factors Encoded by Genes on Mobile Genetic Elements

Pathogenicity Islands

Large groups of genes that are associated with pathogenicity and are located on the bacterial chromosome are termed pathogenicity islands (PAIs). They are large organized groups of genes, usually 10–200 kb in size. The major properties of PAIs are as follows: they have one or more virulence genes; they are present in the genome of pathogenic members of a species but absent in the nonpathogenic members; they are large; they typically have a different guanine plus cytosine (G + C) content than the rest of the bacterial genome; they are commonly associated with tRNA genes; they are often found with parts of the genome associated with mobile genetic elements; they often have genetic instability; and they often represent mosaic structures with components acquired at different times. Collectively, the properties of PAIs suggest that they originate from gene transfer from foreign species. A few examples of PAI virulence factors are provided in Table 2.

Table2. A Few Examples of the Very Large Number of Pathogenicity Islands of Human Pathogens

الاكثر قراءة في البكتيريا

الاكثر قراءة في البكتيريا

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)