Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-06-27

Date: 2025-01-27

Date: 2023-06-21

|

The phonology of- ify derivatives

Mahn (1971) observed what I consider to be the most important prosodic property of -ify derivatives, namely that the syllable preceding -ify always carries main stress. Gussmann (1987) arrives at two generalizations, namely that -ify attaches to bases ending in the vowel /i/, which is deleted by a phonological rule, and to bases ending in an obstruent, followed by an optional sonorant. As he himself admits, these rules are insufficient because they overgenerate and do not cover all attested derivatives. In his analysis of 164 derivatives taken from the entire OED, E. Schneider (1987) again emphasizes the fact that -ify needs to be immediately adjacent to a main-stressed syllable, with the consequence that -ify tends to attach to monosyllables (as in falsify) and words with final stress (e.g. dìvérsify). With bases ending in an unstressed vowel, the final vowel coalesces with the suffix (béautif̀y) with consonant-final trochees as base words stress is shifted to the base-final syllable. As we will see, these generalizations (apart from stress shift) hold also for 20th century neologisms. Kettemann (1988) discusses a number of lexicalized stem alternations, but does not arrive at significant phonological constraints on -ify derivatives.

Of the 23 derivatives in the neologism corpus, 15 formations are based on monosyllabic stems or on iambic stems )artify, bourgeoisify, jazzify, karstify, massify, mucify, mythify, negrify, opacify, plastify, sinify, technify, trustify, tubify, youthify). Three forms have bases ending in an unstressed vowel, which is systematically truncated (ammonia - ammonify, gentry gentrify, Nazi - Nazify, yuppy - yuppify). Stress lapses are absolutely pro hibited, all derivatives have primary stress on the syllable immediately preceding the suffix. Stress shift is apparently a rare phenomenon (passívifỳ, probabílifỳ, syllábifỳ, and arídify). Deletion of base-final consonants is not attested at all.

How can this behavior be accounted for? I propose that -ify is subject to the same constraint hierarchy as -ize derivatives, with the prosodic differences between the two types of derivatives resulting from the prosodic differences of the suffixes (one monosyllabic, the other disyllabic with a light penult).

A comparison of the prosodic properties of derivatives in -ify with those in -ize reveals that the phonological constraints lead to a (nearly) complementary distribution of the two suffixes: -ize is generally preceded by trochaic or dactylic bases, i.e. it needs an unstressed or secondarily stressed syllable to its left, whereas -ify always needs a main-stressed syllable to its left (stress shift is generally avoided).1 Taking into account that, the two suffixes are synonymous, we can hypothesize that we are dealing with two phonologically conditioned allomorphs, more specifically with one of the rare cases of phonologically conditioned suppletion in derivational morphology, (cf. Carstairs McCarthy 1988, Carstairs 1990).

In a rule based framework, this state of affairs would be expressed by two (or more) different rules which exhaust all possible environments. In an OT approach, both allomorphs are found among the candidates, which are evaluated in parallel by only one constraint hierarchy. As usual, the derivative which best satisfies the constraints is chosen as optimal (see e.g. Booij 1998 for illustration). Thus, if the two competing suffixes under discussion are indeed phonologically-conditioned allomorphs, two predictions can be made. First, the phonological shape of -ify derivatives and of -ize derivatives result from the same constraint hierarchy, i.e. the one a ready proposed for -ize derivatives. Secondly, the choice between -ize and ify is determined by the very same hierarchy. As we will see, both predictions are correct.

Let us begin with the first prediction. As already mentioned, -ify derivatives have strictly ante-penultimate main stress. This pattern is exactly that of English nouns: polysyllables with a light penultima have antepenultimate main stress. Hence, stress placement results from the ranking in (1), which we already know from the preceding topic:

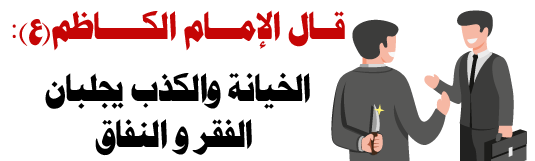

Due to the fact that -ify attachment automatically leads to a light penult in the derived form, two violations of R-ALIGN-HEAD are inevitable. Attempts to shift main stress further to the right in order to better satisfy R-ALIGN-HEAD are unsuccessful, because this entails violation of higher-ranked constraints (see candidates (1b), (1c) and (1d)). Notably, derivatives with iambic or monosyllabic bases fulfill these constraints optimally without any necessary stem allomorphy effects such as deletion of segments, destressing, or stress shift.

But why is it that -ify systematically does not attach to trochees or dactyls? If we include both -ize and -ify derivatives in the candidate sets the correct distribution emerges. With trochaic or dactylic bases, -ize derivatives necessarily involve one violation less than candidates with -ify, because -ize is monosyllabic:2

Only a stress shift or the truncation of the base-final rhyme could improve the -ify derivative, but IDENT-HEAD and MAX-C are higher-ranked than R-ALIGN-HEAD, which rules out this option.3 With dactylic bases parallel arguments can be adduced, to the effect that -ize attachment always emerges as more optimal than -ify attachment.

With monosyllabic bases, or bases ending in a main-stressed syllable, -ify is selected as the optimal allomorph:

As already mentioned, there are only very few exceptional cases where -ize is attached in spite of the resulting stress clash (banálìze, Czéchìze, écìze, Márxìze, quántìze, routínìze). These are exceptional formations because they are less optimal than the expected forms !banálify, !Czechify (cf. Anglify, Russify), !ecify, and !Marxify.

With regard to the selection of the optimal suffix, there is one problematic set of candidates, those on the basis of trochaic stems with an unstressed final [ɪ]. As pointed out by previous authors and as evidenced by the forms gentrify, Nazify and yuppify, such base words readily take -ify (under deletion of the base-final vowel), but as we have seen, such base words also may take -ize as a suffix (cf. dolbyize). Hence our constraints should allow two optimal can didates. Interestingly, there are indeed at least two forms with doublets attested (both with their first citation before the 20th century): Torify, Toryize and dandify, dandyize. The form in -ize seems to be more optimal than the -ify derivative because it does not involve the deletion of the base final vowel. However, the -ify derivative satisfies both ONSET and DEP. In other words, a violation of MAX-V (as in Torify) is sometimes preferred to a violation of either ONSET or DEP. Thus we are faced-with a variable ranking of ONSET, DEP, and MAX-V:

The following tableaux illustrate this:

(5)

If DEP or ONSET has the lowest rank, the -ize derivatives emerges as optimal. If MAX-V is lowest, -ify is attached. The emergence of different optimal pronunciations of dandyize is desirable, since, both glide insertion and onsetless pronunciation are possible. The nature of this variation in constraint rankings and its theoretical implication certainly merit further investigation. For the purposes of this study we simply state that the observed variability can best be accounted for by a variable constraint ranking within a small subset of constraints in the overall hierarchy.

The ranking in (5c) can also account for the only remaining derivative based on a vowel-final stem, ammonify, which features otherwise unattested truncation (cf. ammonia). The pertinent constraints are RLGHT-ALIGN-HEAD, MAX-V, ONSET and DEP:

Candidate (6a) is optimal because it only violates low-ranked MAX-V. The singleton truncation effect is therefore straightforwardly explained by the proposed hierarchy.

The variable ranking of MAX-V, ONSET and DEP has consequences if we look again at -ize derivatives. In particular, we need to reconsider the behavior of schwa-final trochaic bases. It was argued that such bases feature glottal stop insertion, if suffixed by -ize (cf. !mora[ʔ]ize). Even if competing candidates in -ify are taken into account, the proposed ranking in (5a) predicts that !mora[ʔ]ize as optimal. However, !morify is the optimal candidate under ranking (5c), because it only violates low-ranking MAX-V. Native speakers seem not to have strong intuitions about such words, and generally prefer syntactic constructions instead or alternative coinages where parallel forms are more frequent, such as !moraicize. One of the reasons for the insecurity of speakers may be that by looking exclusively at -ize derivatives no evidence for the ranking of MAX-V on the one hand and DEP and ONSET on the other can be found, because MAX-V does not interact with DEP and ONSET. In any case, the foregoing remarks about the behavior of schwa-final trochaic bases remain somewhat tentative. Given the rarity of potential base words of this phonological shape in English in general this is, however, a marginal problem.

The proposed rankings of MAX-V, DEP and ONSET lead to a slight modification of the lower part of the proposed hierarchy. The complete hierarchy is presented in (11), with variable rankings indicated by '%':

To summarize, the proposed constraint hierarchy for -ize and -ify derivatives does not only account for the stress pattern and allomorphy effects of -ize derivatives, but also for the phonological shape and restrictions on -ify derivatives and the distribution of the two competing suffixes. Thus, we can explain why monosyllabic bases avoid -ize but take -ify and why -ify only attaches to main stressed syllables. In informal terms, -ize is selected to make the main stress fall as far to the right as possible, whereas -ify is chosen to avoid a stress clash.

Only four of the -ify neologisms seem to go against the prediction of the proposed model, since they apparently exhibit a shift of the main stress (passívifỳ, probabílifỳ, syllábifỳ, and arídifỳ). I will discuss each of them in turn.

Passívifỳ is an early 20th century rival of passivate and did not become established later, which can be interpreted as an indication of its slight oddness. Note also that passívifỳ was subsequently never attested as a rival of passivize, which indicates the well-formedness of pássivìze as compared to passívifỳ. Probabílifỳ is attested with a meaning slightly different from that of probábilìze, and this meaning crucially is based on the noun probabílity rather than on the adjective próbable (cf. the quotations and definitions in the OED). Hence, there is evidence that probabílifỳ is not derived from the base probable, but from probabílity, with the consequence that there is no IDENT-HEAD violation because the prosodic head of probabílity is the same as the prosodic head of probabílifỳ.4 Syllábify is a back-formation from syllabification, which in turn seems to be coined directly on the basis of Latin syllabificare. The only remaining odd form is arídifỳ, whose analogy to the semantically related (and equally exceptional) form humídifỳ is striking, the latter word being first attested some 40 years earlier (1884). In sum, the forms apparently violating IDENT-HEAD can either be explained on a paradigmatic basis by local analogy, or they did not survive for a longer period of time.

Contrary to this analysis, Kettemann (1988:92ff) argues that stress shift is a productive phenomenon with -ify derivatives. He bases his claim on a little experiment, where subjects had to suffix -ify to the nonce base sarid, which resulted in 70% answers involving a stress shift. In my view, this result, though impressive, does not demonstrate what Kettemann thinks it does, because the test item rhymes with adjectives such as arid, humid, solid, so that the choice of stress shift may well be triggered by this phonological similarity of the nonce forms with the attested and established forms arídifỳ, humídifỳ, solídifỳ. Thus Kettemann's experiment should not be interpreted as a sign of productivity of stress shift. If stress shift were indeed productive, I do not see any explanation for the almost complementary distribution of -ify and -ize based on the stress pattern of the base. Why did none of the over two hundred trochaic and dactylic bases that took -ize as a suffix chose -ify as a suffix with simultaneous stress shift? If stress shift were productive, -ify should occur much more often with trochaic and dactylic bases.

To summarize the analysis, we can state that -ify and -ize are synonymous suffixes whose distribution is governed by the constraint hierarchy in (7). Hence the two suffixes constitute a case of phonologically conditioned suppletion, which is rarely found in derivational morphology, according to Carstairs-McCarthy (1988) and Carstairs (1990).

1 This would amount to perfect complementary distribution, if it were not for disyllabic bases ending in unstressed [ɪ], which trigger truncation of these rhymes. See below for discussion.

2 In those cases where the following tableaux also include -ize derivatives, only the optimal -ize derivative is given as a candidate.

3 I assume that there are high-ranked faithfulness constraints that prohibit suffix allomorphy with both -ize and -ify. Hence no deletion of suffix material is possible, which rules out candidates such as *randomfy or *randomif, for example.

4 In a similar fashion, the segmental alternation in opacify can be explained, cf. opacity.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|