Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-05-04

Date: 2024-04-03

Date: 2024-02-23

|

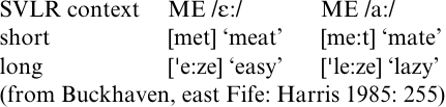

Justifying the S in SVLR

If we are to establish SVLR as a Scots-specific phonological rule, we must first challenge Agutter's contention that `the context-dependent vowel length encapsulated in SVLR is not and perhaps never was Scots specific' (1988b: 20). I shall show that SVLR can be defended synchronically as a Scots-specific process; there is also evidence that SVLR was historically introduced only into Scots.

Harris (1985: ch.4) discusses the chequered history of Middle English /ε:/, the vowel of the MEAT class of lexical items. This class, although intact at the beginning of the early Modern English period, had merged in standard dialects by the eighteenth century with the MEET class. Controversy exists, however, over whether the MEAT class earlier merged with the MATE class (5 ME /a:/) before splitting and re merging with Middle English /e:/ at /i:/ (Dobson 1957, Luick 1921). Harris believes that a consideration of some Modern English dialects which retain a three-way contrast of MEET, MEAT and MATE words may shed further light on the dubious history of /ε:/; from our point of view, what is interesting is the strategies which dialects of different areas have implemented to keep these classes of words, with Middle English /ε: e: a:/, distinct.

MEET-MEAT-MATE contrasts persist in many varieties of conservative Hiberno-English (Harris 1985: 232), various rural English dialects (Wells 1982), and some Scots dialects (Catford 1958). Harris discusses several strategies whereby dialects preserve the MEET-MEAT MATE contrasts, including diphthongization; the `leapfrogging' of the reflex of Middle English /a:/ past that of /ε:/; and the use of length contrasts. However, these strategies are not evenly distributed across English and Scots dialects.

Harris considers five Modern Scots dialects which keep their reflexes of Middle English /ε: e: a:/ distinct ± those of north-east Angus, Kirkcud bright, east Fife, Shetland northern Isles/Yell/Unst, and Shetland main land/Skerries. One of these, Kirkcudbright, is a `core', central Scots dialect with full implementation of SVLR, so that /i e e̟/, the reflexes of Middle English /e: ε: a:/, are all positionally long or short. However, `the other four dialect areas are typical of geographically peripheral areas of Scotland where Aitken's Law has not gone to completion' (Harris 1985: 254). Here, while the /i e/ reflexes of Middle English /e: ε:/ are subject to SVLR, the reflex of Middle English /a:/, which is /ε:/ in north-east Angus and Shetland northern Isles/Yell/Unst and /e:/ in east Fife and Shetland mainland/Skerries, is phonemically long. That is, in east Fife and Shet land mainland/Skerries, the reflexes of Middle English /ε:/ and /a:/ are qualitatively identical. However, SVLR affects one vowel, /e/ /ε:/, while phonemic length remains in /e:/ , /a:/. The length difference is, of course, neutralized in SVLR long contexts, but is sufficient to maintain the contrast elsewhere, as can be seen from (1).

The other three Scots dialects all differentiate Middle English /ε:/ from /a:/ qualitatively, as /e/ versus /e̟/ in Kirkcudbright and /e/ versus /ε:/ in north-east Angus and Shetland northern Isles/Yell/Unst. The latter two dialects use conditioned versus phonemic length as an additional distinguishing strategy.

The significance of this dialect evidence for the status of SVLR becomes apparent from Harris's comparison with five English dialects which also maintain a three-way MEET-MEAT-MATE contrast. In all the English cases, the reflex of Middle English /ε:/ or /a:/ (or both) has diphthongized. In addition, some dialects preserve the original relative heights of these vowels, as in Westmorland, with /iə/ ME /ε:/ and /ea/ Middle English /a:/, while others reverse them; so, Devon and Corn wall has /εi/ Middle English /ε:/ but /e:/ Middle English /a:/. None of the English dialects uses vowel length differences to keep the MEAT MATE-distinction, since they all retain the reflexes of Middle English /e: E: a:/ as phonemically long vowels or diphthongs and, in the absence of SVLR, there is no phonemic versus positionally determined length dichotomy. However, four out of the five Scottish dialects discussed by Harris maintain the MEAT-MATE distinction by exploiting the length difference created by the incomplete operation of SVLR, either as the sole distinguishing factor or along with the preservation of the relative vowel heights. The sole exception is Kirkcudbright, where SVLR has been implemented fully and no phonemically long vowels remain. No Scottish dialect uses the strategy of diphthongization; this is in keeping with the tendency of Modern Scots and SSE long vowels to be realized as long steady-state monophthongs rather than sequences of vowel plus offglide. The geographical skewing of the different strategies employed in maintaining a MEET-MEAT-MATE distinction lends support to the hypothesis that SVLR was introduced diachronically only into Scots.

|

|

|

|

للتخلص من الإمساك.. فاكهة واحدة لها مفعول سحري

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العلماء ينجحون لأول مرة في إنشاء حبل شوكي بشري وظيفي في المختبر

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم العلاقات العامّة ينظّم برنامجاً ثقافياً لوفد من أكاديمية العميد لرعاية المواهب

|

|

|