Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-04-16

Date: 2023-12-25

Date: 2024-08-23

|

First, though there can be no objection to considering the verbalizations of fluent speakers to be ‘linguistic responses’, one must not suppose that, in this context, ‘response’ means what it usually means: ‘A stimulus-occasioned act. An (act) correlated with stimuli, whether the correlation is untrained or the result of training ’ (Kimble, 1961, glossary). On the contrary, a striking feature of linguistic behavior is its freedom from the control of specifiable local stimuli or independently identifiable drive states. In typical situations, what is said may have no obvious correlation with conditions in the immediate locality of the speaker or with his recent history of deprivation or reward. Conversely, the situations in which such correlations do obtain (the man dying of thirst who predictably gasps ‘Water’) are intuitively highly atypical.

Indeed, the evidence for the claim that linguistic responses are responses in the strict sense would appear to be non-existent. There is no more reason to believe that the probability of an utterance of ‘ book ’ is a function of the number of books in the immediate locale than there is to believe that the probability of an utterance of the word ‘ person ’ or ‘ thing ’ is a function of the number of persons or things in view. Lacking such evidence, what prompts one to these beliefs is, first, a confusion of the strict sense of ‘response’ (‘a stimulus-correlated act ’) with the loose sense in which the term applies to any bit of behavior, stimulus-correlated or otherwise; and second, a philosophy of science which erroneously supposes that unless all behavior is held to consist of responses in the strict sense some fundamental canon of scientific method is violated. But the claim that behavior consists solely of responses cannot be established on methodological grounds alone. On the contrary, such a claim constitutes an extremely geneal empirical hypothesis about the degree to which behavior is under the control of specifiable local stimulation.

The second inadequacy of simple S-R models of language is also a consequence of the identification of verbalizations with responses. In laboratory situations, an organism is said to have mastered a response when it can be shown that it produces any of an indefinite number of functionally equivalent acts under the appropriate stimulus conditions. That some reasonable notion of functional equivalence can be specified is essential, since we cannot, in general, require of two actions that they be identical either in observable properties or in their physiological basis in order to be manifestations of the same response. Thus, a rat has ‘got’ the bar-press response if and only if it habitually presses the bar upon food deprivation. Whether it presses with its left or right front paw or with three or six grams of pressure is, or may be, irrelevant. Training is to some previously determined criterion of homogeneity of performance, which is another way of saying that what we are primarily concerned with are functional aspects of the organism’s behavior. We permit variation among the actions belonging to a response so long as each of the variants is functionally equivalent to each of the others. In short, a response is so characterized as to establish an equivalence relation among the actions which can belong to it. Any response for which such a relation has not been established is ipso facto inadequately described.

We have just suggested that it is not in general possible to determine stimuli with which verbal responses are correlated. It may now be remarked that it is not in general possible to determine when two utterances are functionally equivalent, i.e., when they are instances of the same verbal response. This point is easily overlooked since it is natural to suppose that functional equivalence of verbal responses can be established on the basis of phonetic or phonemic identity. This is, however, untrue. Just as two physiologically distinct actions may both be instances of a bar-press response, so two phonemically distinct utterances may be functionally equivalent for a given speaker or in a given language. Examples include such synonymous expressions as ‘bachelor’ and ‘unmarried man’, ‘perhaps’ and ‘maybe’, etc. Conversely, just as an action is not an instance of a bar-press response (however much it may resemble actions that are) unless it bears the correct functional relation to the bar, so two phonemically identical utterances - as, for example, utterances of ‘ bank ’ in (1) and (2) - may, when syntactic and semantic considerations are taken into account, prove to be instances of quite different verbal responses:

(1) The bank is around the corner.

(2) The plane banked at forty-five degrees.

It appears, then, that the claim that verbal behavior is to be accounted for in terms of S-R connections has been made good at neither the stimulus nor the response end. Not only are we generally unable to identify the stimuli which elicit verbal responses, we are also unable to say when two bits of behavior are manifestations of the same response and when they are not. That this is no small difficulty is evident when we notice that the problem of characterizing functional equivalence for verbal responses is closely related to the problem of characterizing such semantic relations as synonymy; a problem for which no solution is at present known (cf. Katz and Fodor, 1963).

Finally, the identification of verbalizations with responses suffers from the difficulty that verbalizations do not admit of such indices of response strength as frequency and intensity. It is obvious, but nevertheless pertinent, that verbal responses which are equally part of the speaker’s repertoire may differ vastly in their relative frequency of occurrence (‘heliotrope’ and ‘and’ are examples in the case of the idiolect of this writer), and that intensity and frequency do not covary (the morpheme in an utterance receiving emphatic stress is not particularly likely to be a conjunction, article, preposition, etc., yet these ‘grammatical’ morphemes are easily the most frequently occurring ones). What is perhaps true is that one can vary the frequency or intensity of a verbal response by the usual techniques of selective reinforcement.2 This shows that verbal behavior can be conditioned but lends little support to the hypothesis that conditioning is essential to verbal behavior.

Faced with these and other difficulties, a number of learning theorists have acknowledged the necessity of abandoning the simpler S-R accounts of language. What has not been abandoned, however, is the belief that some version of conditioning theory will prove adequate to explain the characteristic features of verbal behavior, and, in particular, the referential functions of language. I wish to consider the extent to which more complicated versions of conditioning theory may succeed where simple S-R models have failed.

The strength of single-stage S-R theories lies in the fact that they produce an unequivocal account of what it is for a word to refer to something. According to such theories, w refers to x just in case:

(3) There is a response R such that the presentation of x increases the probability of R, and such that R is non-verbal;

(4) the utterance of w increases the probability of R being produced by a hearer;

(5) the presentation of x increases the probability of the utterance of w.

Thus, on the S-R account, ‘apple’ refers to apples just because

(6) there is some non-verbal response (reaching, eating, salivating, etc.) the probability of which is increased by the presentation of apples, and

(7) the utterance of ‘ apple ’ tends to increase the probability of that response being produced by a hearer;

(8) the presentation of apples tends to increase the probability of the utterance of ‘apple’.

The weakness of the single-stage S-R theory lies largely in the failure of words and their referents to satisfy conditions (4) and (5). That is, utterances of words do not, in general, serve as stimuli for gross, non-verbal responses, nor can such utterances in general be viewed as responses to specifiable stimuli. What is needed, then, is a version of conditioning theory which provides an account of reference as explicit as that given by single-stage S-R theories; but does not require of verbalizations that they satisfy such postulates as (4) and (5). It has been the goal of much recent theorizing in psycholinguistics to provide such an account in terms of mediating responses.

Consider, for example, the following passage from Mowrer (1960, p. 144):

As Fig. 1 shows, the word ‘Tom’ acquired its meaning, presumably, by being associated with, and occurring in the context of, Tom ad a real person. Tom himself has elicited in John, Charles, and others who have firsthand contact with him a total reaction that we can label Rt, of which rt is a component. And as a result of the paired presentation of occurrence of ‘ Tom’-the-word and Tom-the-person, the component, or ‘detachable’, reaction, rt, is shifted from the latter to the former.

It is clear that this theory differs from S-R theories primarily in the introduction of the class of constructs of which rt is a member. In particular, it is with rt the ‘detached component’, and not with Rt the gross response, that Mowrer identifies the meaning of the word ‘Tom’.

The differences between rt and Rt thus determine the difference between Mowrer’s approach to verbal behavior and single-stage theories. In particular,

(9) while Rt is an overt response, or, at any event, a response that may have overt components, rt is a theoretical entity; a construct postulated by the psychologist in order to explain the relation between such gross responses as Rt and such stimuli as utterances of ‘Tom’. Hence,

(10) occurrences of mediating responses, unlike occurrences of overt responses, are not, in general, directly observable. Though it may be assumed that progress in physiology should uncover states of organisms the occurrence of which may be identified with occurrences of mediating responses, rt and other such mediators are, in the first instance, functionally characterized. Hence, whatever evidence we have for the correctness of the explanatory models in which they play a role, is ipso facto evidence for their existence.

(11) The relation of rt to Rt is that of proper part to whole. It is important to notice that for each ri and Ri, ri = Ri is a basic assumption of this theory. In each case where it does not hold, mediation theory is indistinguishable from single-stage theory. To put it the other way around, single-stage theory is the special case of mediation theory where ri = Ri.

It is clear that the introduction of mediating responses such as rt will render a learning-theoretic approach to meaning impervious to some of the objections that can be brought against single-stage theories. For example, the failure of verbalization to satisfy (4) and (5) is not an objection to theories employing mediating responses, since it may be claimed that verbalizations do satisfy (12) and (13).

(12) If ri is a mediating response related to wi as rt is related to ‘Tom’; then the utterance of wi increases the probability of ri.

(13) If Si is an object related to Ri as Tom is related to Rt, and if ri is a mediating response related to Ri as rt is related to Rt; then the presentation of Si increases the probability of ri. Since mediating responses are not directly observable, and since the psychologist need make no claim as to their probable physiological basis, such postulates as (12) and (13) may prove very difficult to refute.

The result of postulating such mediating events as rt in the explanation of verbal behavior is, then, that an account of reference may be given that parallels the explanation provided by single stage S-R theories except that (4) and (5) are replaced by (12) and (13). Roughly speaking, a word refers to an object just in case first, utterances of the word produce in hearers a mediating response that is part of the gross response that presentation of the object produces and second, presentation of the object produces in speakers a mediating response which has been conditioned to occurrences of the relevant word.

A rather natural extension of Mowrer’s theory carries us from an explanation of how words function as symbols to an account of the psychological mechanisms underlying the understanding and production of sentences:

What, then, is the function of the sentence ‘Torn is a thief’? Most simply and most basically, it appears to be this. ‘Thief’ is a sort of ‘unconditioned stimulus’. . .which can be depended upon to call forth an internal reaction which can be translated into, or defined by, the phrase ‘a person who cannot be trusted’, one who ‘takes things, steals’. When, therefore, we put the word, or sign, ‘Tom’ in front of the sign ‘thief’, as shown in Fig. 2, we create a situation from which we can predict a fairly definite result. On the basis of the familiar principle of conditioning, we would expect that some of the reaction evoked by the second sign, ‘thief’, would be shifted to the first sign, ‘Tom’, so that Charles, the hearer of the sentence, would thereafter respond to the word ‘Tom’, somewhat as he had previously responded to the word ‘thief’ (p. 139).

Or, as Mowrer puts it slightly further on,

[The word ‘thief’ is] presumed to have acquired its distinctive meaning by having been used in the presence of, or to have been, as we say, ‘associated with’ actual thieves. Therefore, when we make the sentence, ‘Tom (is a) thief’, it is no way surprising or incomprehensible that the rt reaction gets shifted. . .from the word, ‘thief’ to the word, ‘Tom’ (p. 144).

It thus appears to be Mowrer’s view that precisely the same process that explains the shifting of rt from occasions typified by the presence of Tom to occasions typified by the utterance of ‘Tom’ may be invoked to account for the association of the semantic content of the predicate with that of the subject in such assertive sentences as ‘Tom is a thief’. In either case, we are supposed to be dealing with the conditioning of a mediating response to a new stimulus. The mechanism of predication differs from the mechanism of reference only in that in the former case the mediating response is conditioned from a word to a word and in the latter case from an object to a word.

Thus, a view of meaning according to which it is identified with a mediating response has several persuasive arguments in its favor. First, it yields a theory that avoids a number of the major objections that can be brought against single stage S-R theories. Second, it appears to provide an account not only of the meaning of individual words, but also of the nature of such essential semantic relations as predication. Third, like single-stage S-R theories, it yields a conception of meaning that is generally consonant with concepts employed in other areas of learning theory. It thus suggests the possibility that the development of an adequate psycholinguistics will only require the employment of principles already invoked in explaining non-verbal behavior. Finally, these benefits are to be purchased at no higher price than a slight increase in the abstractness permitted in psychological explanations. We are allowed to interpose s-r chains of any desired length between the S’s and R’s that form the observation base of our theory. Though this constitutes a proliferation of unobservables, it must be said that the unobservables postulated are not different in kind from the S’s and R’s in terms of which single-stage theories are articulated. It follows that, though we are barred from direct, observational verification of statements about mediating responses, it should prove possible to infer many of their characteristics from those that S’s and R’s are observed to have.

Nevertheless, the theory of meaning implicit in the quotations from Mowrer cited above is thoroughly unsatisfactory. Nor is it obvious that this inadequacy is specific to the version of the mediation theory that Mowrer espouses. Rather, I shall try to show that there are chronic weaknesses which infect theories that rely upon mediating responses to explicate such notions as reference, denotation, or meaning. If this is correct, then the introduction of such mediators in learning-theoretic accounts of language cannot serve to provide a satisfactory answer to the charges that have been brought against single-stage theories.

In the first place, we must notice that Mowrer’s theory of predication at best fails to be fully general. Mowrer is doubtless on to something important when he insists that a theory of predication must show how the meaning of a sentence is built up out of the meanings of its components. But it is clear that the simple conditioning of the response to the predicate to the response to the subject, in terms of which Mowrer wishes to explain the mechanism of composition, is hopelessly inadequate to deal with sentences of any degree of structural complexity. Thus, consider:

(14) ‘Tom is a perfect idiot.’

Since what is said of Tom here is not that he has the properties of perfection and idiocy, it is clear that the understanding of (14) cannot consist in associating with ‘Tom’ the responses previously conditioned to ‘perfect’ and ‘idiot’. It is true that the meaning of (14) is, in some sense, a function of the meaning of its parts. But to understand (14) one must understand that ‘perfect’ modifies ‘idiot’ and not ‘ Tom ’, and Mowrer’s transfer of conditioning model fails to explain either how the speaker obtains this sort of knowledge, or how he employs it in understanding sentences. Analogous difficulties can be raised about

(15) ‘Tom is not a thief.’

Lack of generality is, however, scarcely the most serious charge that can be brought against Mowrer’s theory. Upon closer inspection, it appears that the theory fails even to account for the examples invoked to illustrate it. To begin with, the very fact that the same mechanism is supposed to account for the meaning of names such as ‘ Tom ’ and of predicates such as ‘ thief’ ought to provide grounds for suspicion, since the theory offers no explanation for the obvious fact that names and predicates are quite different kinds of words. Notice, for example, that we ask:

(16) ‘What does “thief” mean?’

but not

(17) ‘What does “Tom” mean?’

and

(18) ‘Who is Torn?’

but not

(19) ‘Who is thief?’

All this indicates what the traditional nomenclature already marks: there is a distinction to be drawn between names and predicates. A theory of meaning which fails to draw this distinction is surely less than satisfactory.

Again, it is certainly not the case that, for the vast majority of speakers, ‘thief’ acquired its meaning by ‘having been used in the presence of. . .actual thieves’. Most well brought up children know what a thief is long before they meet one, and are adequately informed about dragons and elves though encounters with such fabulous creatures are, presumably, very rare indeed. Since it is clearly unnecessary to keep bad company fully to master the meaning of the word ‘thief’, a theory of language assimilation must account for communication being possible between speakers who have in fact learned items of their language under quite different conditions. Whatever it is we learn when we learn what ‘thief’ means, it is something that can be learned by associating with thieves, reading about thefts, asking a well-informed English speaker what ‘thief’ means, etc. Though nothing prevents Mowrer from appealing to some higher-level conditioning to account for verbal learning of linguistic items, it is most unclear how such a model would explain the fact that commonality of response can be produced by such strikingly varied histories of conditioning.

Nor does the mediation theory of predication appear to be satisfactory. It is generally the case, for example, that conditioning takes practice, and that continued practice increases the availability of the response. But, first, there is no reason to suppose that the repetition of simple assertive sentences is required for understanding, or even that it normally facilitates understanding. On the contrary, it would appear that speakers are capable of understanding sentences they have never heard before without difficulty, that the latency for response to novel sentences is not strikingly higher than the latency for response to previously encountered sentences (assuming, of course, comparability of length, grammatical structure, familiarity of vocabulary, etc.), and that repetition of sentential material produces ‘semantic satiation ’ rather than increase of comprehension. Second, the conditioning model makes it difficult to account for the fact that we do not always believe what we are told. Hearing someone utter ‘ Tom is a thief’ may, of course, lead me to react to Tom as I am accustomed to react to thieves; but I am unlikely to lock up the valuable unless I have some reason to believe that what I hear is true. Though this fact is perfectly obvious, it is unclear how it is to be accounted for on a model that holds that my understanding of a sentence consists in having previously distinct responses conditioned to one another. It might, of course, be maintained that the efficacy of conditioning in humans is somehow dependent upon cognitive attitude. This reply would not, however, be of aid to Mowrer, since it would commit him to the patently absurd conclusion that a precondition for understanding a sentence is believing that it is true; and, conversely, that it is impossible to understand a sentence one does not believe. Third, if my understanding of ‘Tom is a thief’ consists of a transference of a previously established reaction to ‘thief’ to a previously established reaction to ‘Tom’, it is difficult to account for the fact that I, a speaker who does not know Tom and therefore has no previously established response to utterances of the word ‘Tom’, am perfectly capable of grasping that sentence. It is clear what the story ought to be; I know that ‘ Tom ’ is a name (a bit of information which, by the way, I did not pick up by hearing ‘Tom’ uttered ‘in the presence of. . .or, as we say “ associated with ” ’ names), and I therefore know that the sentence ‘ Tom is a thief’ claims that someone named Tom is a thief. What is not clear, however, is how a story of this sort is to be translated into a conditioning model.

Some more serious difficulties with mediation theories of reference now need to be investigated.

According to our reconstruction, the mediation theorist wishes to hold, in effect, that a sufficient condition of wi standing for Si is that it elicits a response ri such that ri is part of Ri. It is clear, however, that such a theory will require at least one additional postulate: namely, that each fractional response which mediates the reference of an unambiguous sign belongs to one and only one gross response! For, consider the consequence of rejecting this postulate. Let us suppose that the unambiguous word wi evokes the mediating response ri and that ri is a member of both Ri and Rj, the functionally distinct unconditioned gross responses to Si and Sj, respectively. The assumptions that Ri and Rj are functionally distinct and that wi is univocal, jointly entail that Si and Sj cannot both be referrents of wi. But if Si and Sj are not both referrents of wi, then the principle that membership of a fractional response in a gross response is a sufficient condition for the former to mediate references to stimuli that elicit the latter has been violated. For, since ri belongs to both Ri and Rj, applying this principle would require us to say that wi refers both to Si and Sj. Hence, if we are to retain the central doctrine that a sufficient condition for any w to refer to any S is that it elicit a part of the relevant R, we will have to hold that the fractional responses which mediate unambiguous signs are themselves unambiguous, i.e. that they belong to only one gross response. If, conversely, we do not adopt this condition - if we leave open the possibility that ri might belong to some gross response other than Ri - then clearly the elicitation of ri by wi would at best be a necessary condition for wi referring to Si.

The same point can be made in a slightly different way. All the learning-theoretic accounts of meaning we have been discussing agree in holding that ‘ The essential characteristic of sign behavior is that the organism behaves towards the sign... in a way that is somehow “appropriate to” something other than itself’ (Osgood, 1957, p. 354), i.e. that signification depends upon transfer of behavior from significate to sign. The distinctive characteristic of mediation theories is simply that they take it to be sufficient for signification if part of the behavior appropriate to the significate transfers to the sign. Partial identity is held to be adequate because the mediating response is simply those ‘ reactions in the total behavior produced by the significate . . . [that] are more readily conditionable, less susceptible to extinctive inhibition, and hence will be called forth more readily in anticipatory fashion by the previously neutral [sign] stimulus’ (p. 355). In short, mediators are types of anticipatory responses and they act as representatives for the gross responses they anticipate.

But notice that, just as the single-stage theorist must postulate a distinct sort of appropriate behavior (i.e. a distinct gross response) for each distinct significate, so the mediation theorist must postulate a distinct anticipatory response (i.e. a distinct mediator) for each distinct gross response. If this condition were not satisfied, there would exist mediators which can anticipate many different gross responses. Given an occurrence of such an ambiguous mediator, there would be no way of determining which gross response it is anticipating. From this it follows that there would be no way of determining the significance of the sign that elicited the mediator. For the theory only tells us that the significate is that object to which the gross response anticipated by the mediator is appropriate, and this characterization of the significate is informative only if the relevant gross response can be unequivocally specified, given that one knows which mediator has occurred.

Having established the result that the membership of ri in more than one R is incompatible with the assumption that wi is unambiguous, we can now generalize the argument to include the case of ambiguous signs. Since no sign is essentially ambiguous (i.e. no sign is in principle incapable of being disambiguated) there must always be some set of conditions that, if they obtained, would determine which R is being anticipated by a mediating response elicited by an ambiguous sign. This fact permits us to treat each ambiguous w as a family of univocal homonyms. Each member of such a family is assigned a distinct r such that the specification of that r includes whatever information would be required to choose it as the correct disambiguation of a given occurrence of w. Thus a word like ‘ bat ’ would be associated with two mediators the specification of one of which would involve information adequate to certify an occurrence of that word as referring to the winged mammal, while the specification of the other would involve information adequate to certify an occurrence of that word as referring to sticks used in ball games. Each of these mediators would thus correspond to precisely one R.

The treatment of ambiguous signs thus differs in no essential respects from the treatment of univocal ones; an ambiguous sign is simply a set of univocal signs all of which happen to have the same acoustic shape. It thus follows that the same arguments that show that the relation of r’s to R’s must be one to one if mediation theories are to provide a coherent analysis of the reference of univocal signs also show that the relation must be one to one in the case of the r’s that mediate the reference of each of the homonymous members of an ambiguous sign. In either case the assumption of a one to one correspondence avoids the possibility that ri could be part of a response other than that elicited by Si, since for each linguistically relevant r it is now assumed that there is one and only one R of which it is a part. We can now securely adopt the cardinal principle of mediation theories of reference, viz. that wi refers to Si just in case ri belongs to Ri.

Though the adoption of the postulate of a one to one correspondence between mediating and gross responses is clearly necessary if mediation theories are to propose sufficient conditions for linguistic reference, that postulate is subject to two extremely serious criticisms.

In the first place, it would appear that the sorts of response components that become ‘detached’ from gross responses, and which are thus candidates for the position of rm, are not of a type likely to be associated with R’s in a one to one fashion. Rather, they appear to be rather broad, affective reactions that, judging from the results obtained with such testing instruments as the semantic differential, would seem to be common to very many distinct overt responses. Second, even if it should turn out that the detachable components of R’s can be placed in one to one correspondence with them, the following difficulty arises on the assumption that such a correspondence obtains.

If we assume a one to one relation between gross and mediating responses, the formal differences between single-stage and mediation theories disappears. So long as each ri belongs to one and only one Ri, the only distinction that can be made between mediation and single-stage views is that, according to the former but not the latter, some of the members of stimulus-response chains invoked in explanations of verbal behavior are supposed to be unobserved. But clearly this property is irrelevant to the explanatory power of the theories concerned. It is thus not possible in principle that mediation theories could represent a significant generalization of single-stage theories so long as the mediating responses in terms of which they are articulated are required to be in one to one correspondence with the observable responses employed in single-stage S-R theories.

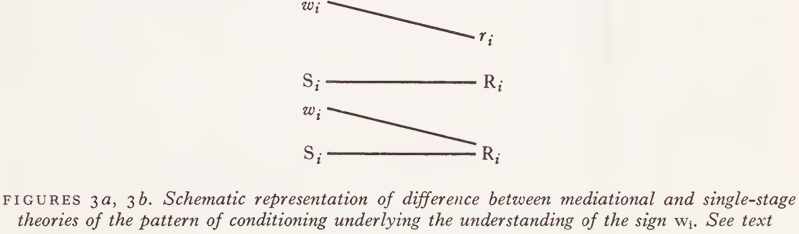

To put it slightly differently, two theories that explain the event en by claiming that it is causally contingent upon a set of prior events e1 e2,. . .en-1 give substantially identical explanations of en if they differ only on the question whether all members of e1. .. en-1 are observable. But it would appear that once a one to one association is postulated between mediating responses and the gross responses of which they are a part, precisely this relation obtains between single-stage and response-mediation explanations of verbal behavior. To put it still differently, once we grant a one to one relation between r’s and R’s, we insure that the former lack the ‘surplus meaning’ characteristic or terms designating bona fide theoretical entities. Hence, only observability is at issue when we argue about whether our conditioning diagrams ought to be drawn as in Fig. 3a or as in Fig. 3b.

If this argument is correct, it ought to be the case that, granting a one to one correspondence between r’s and R’s, anything that can be said on the mediation- theoretic view can be simply translated into a single-stage language. This is indeed the case since, in principle, nothing prevents the single-stage theorist from identifying the meaning of a word with the most easily elicited part of the response to the object for which the word stands (viz., instead of with the whole of that response). Should the single-stage theorist choose to make such a move, his theory and mediation theory would be literally indistinguishable.

In short, the mediation theorist appears to be faced with a dilemma. If his theory is to provide a sufficient condition of linguistic reference, he must make the very strong assumption that a one to one correspondence obtains between linguistically relevant mediators and total responses. On the other hand, the assumption that each mediator belongs to one and only one total response appears to destroy any formal distinction between mediation and single-stage theories, since, upon this assumption, the explanations the two sorts of theories provide are distinguished solely by the observability of the responses they invoke. It is, of course, possible that some way may be found for the mediation theorist simultaneously to avoid both horns of this dilemma, but it is unclear that this has been achieved by any version of mediation theory so far proposed.

1 This work was supported in part by the United States Army, Navy, and Air Force, under Contract D.A. 36-039-AMC-03200 (E), The National Science Foundation (Grant G.P.-2495), The National Institutes of Health (MH-04737-04), The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (N.S.G.-496); and in part by the United States Air Force (E.S.D. Contract A.F. i9(628)-2487). This paper although based on work sponsored by the United States Air Force, has not been approved or disapproved by that Agency. It is reprinted from Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, IV, 1965, 73-81.

2 It is possible to raise doubts about the possibility of operant conditioning of verbal behavior. Cf. Krasner (1958).

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|