Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-04-04

Date: 2023-03-28

Date: 2023-08-18

|

An account of the exact procedure followed in eliciting data from informants will provide important evidence for the recognition of which Guwal verbs fall into the nuclear set. The procedure involved two stages: Guwal-Dyalŋuy, then Dyalŋuy- Guwal:

(1) First, each Guwal word in turn was put to the informant and he was asked for its Dyalŋuy equivalent. A spontaneous reaction was looked for here - the informants were encouraged to say the first thing they thought of, and not to think hard checking if it was correct, or complete enough. Most often a single word correspondent was given; sometimes this was qualified by a number of other words (in grammatical relation to it).

(2) A card was then made out for each Dyalŋuy word, and each Guwal word that the Dyalŋuy word had been given as correspondent for was listed on the card. Cards contained from one to about twenty Guwal words. The informants were then asked each Dyalŋuy word in turn, and asked to give its Guwal equivalent. In each case a single Guwal word was given as the main (or ‘ central ’ - indicated by C) equivalent. The informant was asked for any other Guwal equivalents, and the words on the card checked to see that this was their correct Dyalŋuy correspondent (errors made at stage 1 were corrected here). Taking each Guwal word in turn, the informant was then asked to add something to the Dyalŋuy word in order to distinguish in Dyalŋuy between the Guwal words; he was at this stage encouraged to take his time and think to get a full and correct correspondent.

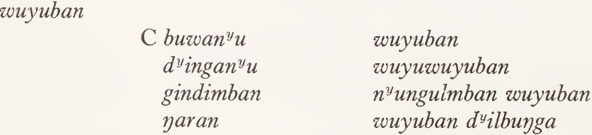

For example, in stage 1 wuyuban had been given as Dyalŋuy correspondent of, amongst others:

buwanyu ‘tell’

dyinganyu ‘ tell a particular piece of news ’

gindimban ‘warn ’

ŋaran ‘ tell someone one hasn’t a certain thing (e.g. food) when one has ’

In stage 2 the informant was asked to verify that wuyuban was a bona fide Dyalŋuy item; he was then asked how he would render wuyuban in Guwal. There were at this stage a number of possibilities open to the informant. He could have said ‘buwanyu, dyinganyu, gindimban, ŋaran. . .’, giving all the items for which he had said wuyuban in stage i; or he could have just mentioned one of the Guwal verbs. In fact his response was of the second type: he simply gave buwanyu as the equivalent of wuyuban; and he had to be prompted - in the second stage - to say that dyinganyu, gindimban, ŋaran, and so on, were also Guwal equivalents of Dyalŋuy wuyuban.

The writer then went into the second stage of elicitation with the other main informant. Exactly the same results were obtained - again just buwanyu was given as Guwal correspondent of wuyuban. And the same thing happened for every one of the Dyalŋuy verbs. Although from two to twenty verbs were listed on each card - those Guwal items for which the Dyalŋuy verb had been given as correspondent in stage 1 - each informant gave just one of these as Guwal equivalent in stage 2; and in each case the two informants picked the same item.

It is fairly obvious what is happening here. Each card contained one nuclear Guwal verb and a number of non-nuclear verbs. When the nuclear Dyalŋuy verb was put to an informant, he always chose the nuclear Guwal verb as its correspondent, never one of the non-nuclear verbs. These results provide not only justification for the nuclear/non-nuclear distinction, but also a procedure for checking which of the everyday language verbs are nuclear.

The writer next checked with the informants that Guwal verbs buwanyu and dyinganyu did differ in meaning, despite the fact that they had both been rendered by the same Dyalŋuy item, wuyuban, in stage 1. The informant was asked how this difference in meaning could be expressed in Dyalŋuy, if it were necessary to do so. He replied that buwanyu would just be rendered by wuyuban but that dyinganyu would be expressed by wuyuwuyuban, with the verb reduplicated. Verbal reduplication in Dyirbal means ‘do it to excess’; thus wuyuwuyuban perfectly conveys the meaning of dyinganyu - calling everyone to gather round as one rather deliberately tells some story or news item. Similarly, when confronted by buwanyu and gindimban, the informant said that for buwanyu the Dyalŋuy translation would be just wuyuban, but that for gindimban it would be nyungulmban wuyuban, involving a transitively verbalized form of the number adjective nyungul ‘one’. nyungulmban wuyuban is literally ‘ tell once ’, an adequate ‘ definition ’ of gindimban within the context of Dyirbal culture. In the case of the pair buwanyu and ŋaran the informant again gave just wuyuban for buwanyu but volunteered wuyuban dyilbuŋga for ŋaran. dyilbu means ‘ nothing ’ and -ŋga is the locative inflection; wuyuban dyilbuŋga is literally ‘ tell concerning (i.e. that there is) nothing’. At this stage the field notebook read:

Effectively, the non-nuclear verbs dyinganyu, gindimban and ŋaran had been defined in terms of nuclear buwanyuwuyuban nothing had been added to the nuclear verb when distinguishing between Guwal pairs in Dyalŋuy - each time buwanyu had been left simply with correspondent wuyuban. The same results were obtained for all the cards, for both informants. The everyday nuclear verb was always left with just the mother-in-law verb as correspondent, and ‘definitions’ were given for the non-nuclear verbs. The ‘ definitions ’ can be seen to be of different syntactic types. Informants sometimes gave identical definitions for a non-nuclear verb, but often rather different ones. However, they agreed in always giving some definition for a non-nuclear verb, and never attempting one for a nuclear word.

Since Dyalŋuy has not been spoken much since 1930 it sometimes required an effort for informants to remember the less frequent Dyalŋuy words. For instance, dyubumban was given for nyuganyu ‘grind’, before yurwinyu was remembered. yurwinyu and nyuganyu are in one-to-one correspondence; dyubumban is the correspondent of bidyin ‘punch (generally: hit with a rounded object)’, dudan ‘mash’, dyilwan ‘kick, or shove with knee’ and dalinyu ‘fall on top of’. The initially suggested correspondence dyubumban for nyuganyu did serve to show the affinity, for speakers of Dyirbal, between the concepts of ‘ grind ’ (as in yurwinyu) and of ‘deliver a blow with a rounded object’ (as in dyubumban). In many other instances initial spontaneous ‘ incorrect ’ correspondents - that were later withdrawn or amended as a more specific Dyalŋuy word was remembered - served to provide valuable insights into the workings of informants’ minds (their internalized semantics) ; clues to semantic relationships from this source were almost always reinforced from other data, and could then be used in assigning semantic descriptions.

An argument between the main Mamu informant and his wife, a speaker of the Dyirbal dialect, over the correct Dyalŋuy correspondent of darbin ‘shake [something] off a blanket’ provided additional evidence for the very general Dyirbal concept ‘set in motion in a trajectory’. The concept is further specified as either ‘set in motion in a trajectory, leaving go of (= throw)’, Dyalŋuy nayŋun„ or else ‘set in motion in a trajectory, holding on to (= shake, wave or bash)’, Dyalŋuy bubaman. The Mamu informant suggested bubaman for darbin, on the grounds that the blanket is held onto; his wife preferred nayŋun since the crumbs (or whatever is being shaken off) do leave the blanket, darbin was clearly identified by both speakers with the general concept ‘set in motion in a trajectory’ but they interpreted the action involved from different points of view, in applying the ‘hold on to/let go of’ criterion, in order to decide on the Dyalŋuy correspondent.1

1 The object of madan/nayŋun is normally ‘that which is thrown’ and of baygun/bubaman ‘that which is shaken’. Since the object of darbin is normally ‘the blanket’ (or whatever is shaken) and not ‘ the crumbs ’ (or whatever is shaken off), bubaman is probably the correct Dyalŋuy correspondent.

|

|

|

|

5 علامات تحذيرية قد تدل على "مشكل خطير" في الكبد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اللجنتان العلمية والتحضيرية تناقش ملخصات الأبحاث المقدمة لمؤتمر العميد العالمي السابع

|

|

|