Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-08-26

Date: 2023-03-25

Date: 2024-08-24

|

The elements B is Rh A and B is A’s will now be explored more fully.1

Compare the following sentences with the main verb have and their corresponding sentences without have:

(18) (i) This line has had three of its ships run aground this year

Three of the ships of this line have run aground this year

(ii) With the new precautions, we will have no more thefts occur in our building

With the new precautions, no more thefts will occur in our building

(iii) He has had it said about him that. ..

It has been said about him that. . .

(iv) The trees on our street are having their lower branches removed

The lower branches of the trees on our street are being removed.

The topic of a passive sentence corresponds to an object of the verb in the equivalent active sentence. (The topic is ordinarily the subject in English.) The above examples show that the topic of a have-construction, however, can correspond to a much larger variety of noun-phrase types in sentences without have. These can include noun phrases in passive sentences other than that of the agentive by + NP. It appears then that topicalizing any one of a variety of noun phrases in certain underlying sentence structures requires it to be raised to subject position in the surface structure with introduction of have, whereas such noun phrases appear in a variety of other surface-structure positions when not topics.2

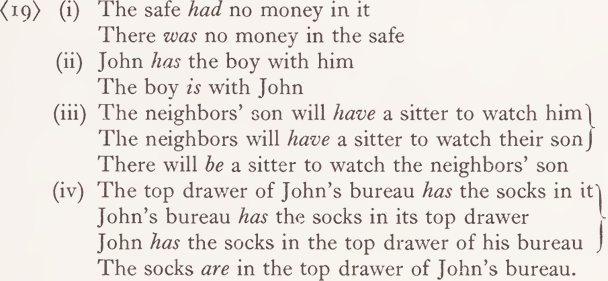

There is a special subclass of have-sentences whose corresponding sentences without have contain the main verb be, such as

(There are other subclasses of have-be correspondences than this one.) For (19 i), for example, the underlying constituents could be roughly represented linearly as follows (omitting Aux and the choice of topic markers):

(20) (not-[there is a B]) + (B is in A) + (B is money) + (A = the safe).3

‘ B is in A’ is an example of the structure which defines this subclass of have- sentences, namely

The subclass, then, has surface structures of the general form A has BXAY.

Furthermore, it is related to a class of surface structures, of more immediate interest here, of the general form A has B which is realized by suppression of ‘ XAY ’. This will be called the ‘ accidental A has B ’. ‘ B is Rh A’, introduced further above, is a component of ‘ B is XAY’, so that the truncated function ‘ is X... Y ’ is a type of ‘ is Rh ’. We can draw examples of the accidental A has B from (19 i-iv) above:

(22) (i) The safe has no money

(ii) John has the boy

(iii) The neighbors’ son will have a sitter

(iv) The neighbors will have a sitter

(v) The top drawer of John’s bureau has the socks

(vi) John’s bureau has the socks

(vii) John has the socks.

It can be seen, further, that any one such A has B sentence may express an indefinite number of state relations between ‘A’ and ‘ B ’, each of which is made explicit by a particular suppressed ‘ XAY ’.

There is a class of A has B sentences, called ‘ inherent ’, which only express one or a restricted number of relations between ‘A’ and ‘ B ’, depending on the particular B-noun or A- and B-nouns occurring. These B-nouns are often relational, such as son, neighbor, assistant, queen, counterpart, end, leg, texture, size, and will be considered to have the basic form C is A’s B, e.g. C is A’s son.4 The inherent A has B is thus related to C is A’s B, as shown next. Where the B-noun is not relational (e.g., This is John’s book), C is A’s B corresponds to other sentences which express the nature of the inherent relation between ‘A’ and ‘B/C’, e.g. John owns/wrote this book.

The B-noun phrase of the accidental relation can occur freely with both definite and indefinite articles or determiners: This box has the diamond, This box has a diamond, The diamond is in this box, There is a diamond (A diamond is) in this box. The inherent relation does not exhibit the same freedom. Thus: John has a son, This is John’s son; but awkward: There is a son of John/of John’s/that is John’s son (or A son is of John/John’s [sow]), John has this son (except where B represents a kind, rather than an individual, e.g. John has the son we would all like to have). Given the constituents ‘there is a C ’ + ‘ C is A’s B’, we would only have a rule that topicalizes A in the form A has a B. Because of the homonymy, some A has B sentences may ambiguously be inherent or accidental, e.g. John has one arm: He lost the other in the war/And he needs another one for the armchair that he’s making.

C is A’s B or B is A’s is marked for a special kind of relation called inherent, whereas A’s B (or A’s) alone can correspond to a wider range of expressions for both accidental and inherent relations, e.g. the shovel that John has: John’s (shovel); the weeds in John’s garden: John’s (weeds); as well as the man that is John’s son: John’s (son). The relations called accidental and inherent are so distinguished because they are logically independent in a way that may be illustrated by the following: (One book is his [book], the other is not.) He has the book that is his, He has the book that is not his, He doesn’t have the book that is his.

In other words, there is no particular difficulty in trying to interpret sentences which say that what someone does or does not happen to have is or is not his. C is A’s B or B is A’s expresses that there is some special relation between ‘A’ and ‘B/C’ as opposed to such accidental relations as may be expressed by the A has B related to B is XAY. In other contexts, the accidental and inherent relations have also been called ‘alienable’ and ‘inalienable’. No claim is made, of course, that the accidental-inherent distinction exists apart from the human view of things, but rather that when a speaker makes an assertion using a form, such as C is A’s B, which we have defined as expressing inherence, he is making the assertion that there is a relation between ‘A’ and ‘B/C’ and that this relation is characterized as being subjectively identified as exclusive and special in some sense. A relation is inherent only when someone says it is or when it cannot be objectively observed as exclusive unless one is told by what objective criteria it is defined as exclusive by a speaker in the given context or by the speakers in the broader context of the culture.

Take again the accidental A has B, which is unmarked for inherence, i.e. for whether there is such a special relation between ‘A’ and ‘ B ’. Imagine a situation in which two people, John and Mary, see a copy of a book lying on a table near Mary and John asks, ‘Do you have that copy?’ By the definition of A has B, we might paraphrase this as ‘ Is there a relation between you and that copy?’ and then expect Mary to be confused on first hearing the question since she can see that John can see that there is a relation. The question would have made better sense as ‘ Is that copy yours?’ since this asks ‘Is there an inherent relation, a special relation that I cannot see, between you and that copy? ’, which is usually a relation of ownership for people and books. Of course, that book instead of that copy would have been easily interpretable since with certain nouns such expressions can also mean ‘any other member of the class of that item ’.

There is a third large A has B class, in addition to still other lesser ones, which is more derivational and semiproductive than truly generative. We can call this the ‘characterizing’ A has B but may not wish to define it as expressing a relation, depending on the definition of reference adopted. Examples of this class and their corresponding be sentences are A has strength: A is strong; A has (much) happiness: A is (very) happy; A has courage: A is courageous.

There are languages which make a formal distinction between their parallels to these three A has B classes and, further, do not introduce a separate verb have when A is the topic. In Hindi, for example, we have: accidental A-ke-paas B hai ‘A-near B is, B is near A’, inherent A-kaa B hai ‘A-of B is, B is of A’, characterizing A-ko B hai ‘A-to B is, B is to A’. Japanese makes a similar distinction. In Hindi, topicalization in such constructions is achieved by word order shifts which also function as equivalents of the definite article in English, lacking in Hindi. For example, A-ke-paas pustak hai ‘A has a book, there is a book near A’, pustak A-ke- paas hai ‘the book is near A, A has the book’. Whether ‘have’ or ‘is near’ is the translation depends in part on whether or not ‘A’ is a person or animate. Compare the Russian u menja kniga ‘by me book, I have a book’, kniga u menja ‘book by me, I have the book’. A has B does not render the inherent relation when B is definite: A-kaa B hai ‘A has a B’ (inherently), B A-kaa hai ‘B is A’s’ (C A-kaa B hai ‘ C is A’s B’).

There are many languages which, like Hindi, express the English have-relation by means of constructions with a verb be, or, where the language has more than one, that be-verb expressing ‘exist’. Furthermore, this have/be is factored out as a component in the inchoative verb A gets B and the causative A gets self B. How-ever, in Newari, a Tibeto-Burman language, all three are expressed by one verb dot-, with inchoative and causative conveyed by separate morphemes: imperfective du ‘be (exist)/have’; perfective dot-o ‘came to be/got’; causative (in the perfective) doe-kol-o ‘caused to be/caused to get’. Still another cross-linguistic parallel supports the idea of have and be as manifestations of the same thing, namely expressions in different languages for the existential there is, there exists. Here languages vary as to whether they express the existential with their equivalent of have or be or some other verb that we would define as containing a component have/be, for example:

In Polish have and be are in complementary distribution with respect to negation: there is is translated hy jest ‘is’, but there is no by an impersonal niema ‘not-has’.

1 For a fuller discussion of have, see Bendix 1966: 37-59, 123-34, and Bach 1967. Cf. also Lyons 1967.

2 This approach has now been made central to the analysis, whereas it was only mentioned as an alternative in the original formulation (Bendix 1966: 102, n. 11) on the basis of a prepublication version of Chomsky 1965.

3 For the slightly different sentence The safe didn’t have money in it, negation is applied with wide scope to the totality of constituents: not-([there is a B] + [B is in A] + [B is money] + [A = the safe]). Bach (1967) has suggested that is, i.e. be, should be excluded from the underlying constituents and introduced by transformation, like have, upon topicalization of certain noun phrases. This would leave ‘B in A’, ‘B money’ and bring us still closer to the formulations of symbolic logic, which have long omitted such connectives as be and have. Is is included here, however, as a metalinguistic device to indicate ‘state’, vs. does for ‘activity’.

4 The genitive construction A’s B will be used throughout to represent, as well, that construction B of A which can be pronominalized to its B, his B, their B, etc., thus excluding such cases as book of poetry, coat of paint, or crowd of people.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|