Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-03-24

Date: 2024-07-13

Date: 2023-03-15

|

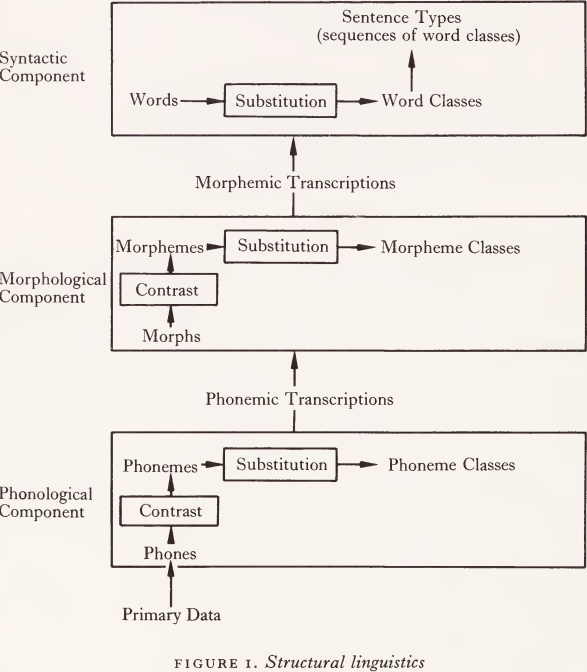

The views of American structureal linguists during the period in which this school was dominant in descriptive linguistics are well represented in Bloomfield (1933) and Harris (1951). As the diagram in Figure 1 suggests, structuralists proposed a model of grammar consisting of several different levels of analysis; the importance of keeping the levels separate being particularly emphasized. This device takes as initial input a body of observable linguistic data consisting of phonetically transcribed utterances along with judgments by native speaker informants as to the sameness or difference, primarily of pairs of words, but sometimes of longer phrases and sentences. It was argued that this primary data could be processed by explicit methods of analysis so as to produce an identification and classification of higher categories such as phonemes and morphemes. The model involves a strong linear directionality away from the primary data. This means that the input to each level must come entirely from the preceding level. One cannot, for example, use morphological information in the identification of phonemes. The approach is operational in that the higher abstract categories of the grammar must be clearly connected to observable data by a series of analytic procedures applied to that data. Thus a phoneme, while it might be roughly defined as a functionally significant class of sounds or phones which does not bear meaning, is, strictly speaking, no more than the result of a set of operations performed on the primary data. The goals of this analysis are essentially classificatory, thus the term taxonomic is often applied to this school of linguistics. All of the operations are based on the notion of formal distribution which is for any element, the list of immediate environments defined by its co-occurrence with other elements of the same type. Two ordered operations are used in the analysis of distributions which we may label contrast and substitution. The functionally significant units of each component (phonemes and morphemes) are identified by contrast. Given distributions for the set of elements at Level N (phones, morphs), the elements of Level N +1 (phonemes, morphemes) are formed in the following way. If two elements of N occur in one or more of the same environments (i.e. if their distributions overlap), they are in contrastive distribution and must become members of different elements at Level N + 1. If, on the other hand, their distributions do not overlap, they are in complementary distribution. Under this condition, the elements are eligible for membership in the same element of N+ 1. Whether or not they are placed in the same element of N + 1 depends, in practice, on such non-distributional considerations as phonetic similarity (for phonemes), meaning (for morphemes) and perhaps some notion of symmetry. The operations are then repeated in the same way for the next highest component which takes as input a transcription provided by the lower component.

Given, now, a set of elements on N + 1, new distributions for these are calculated and the elements classified on this level by substitution. If two or more elements occur in many of the same environments (i.e. their distributions are similar), they are placed in the same class. It should be noted that both operations can apply to the same data. Contrast is involved in the transition from level to level within components while substitution operates only within a given level.

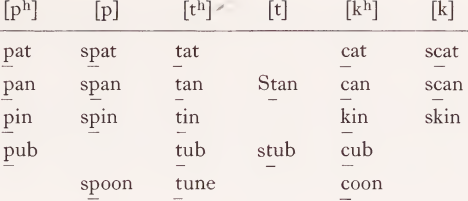

An example from English may be helpful. Consider the following voiceless stops where [p] is bilabial, [t] is alveolar, [k] is velar and [h] indicates aspiration. Suppose that the distribution of each is represented accurately below where the environments are given in English orthography and the element under consideration is underlined.

Applying contrast to these distributions we may note that [p], [t] and [k] all occur only in the general environment # s-V (where # is a word boundary and V is any vowel), while [ph], [th], and [kh] occur only in the environment #-V. Thus, [ph], for example, is in contrast with [th] and [kh] and in complementary distribution with [p], [t] and [k]. On the basis of this evidence, along with considerations of phonetic similarity, the phonemic solution would be:

Substitution is then applied to classify /p/, /t/, /k/ together on the grounds that they occur in many of the same environments when new distributions are calculated for the phonemic level. If substitution is seriously applied to all environments on this level the result is normally a set of intersecting classes and, given the interest of linguists in discrete categories, this may account, in part, for the relative neglect of this operation in phonology in favor of a classification based on phonetic similarity.

These operations are repeated on the level of morphology producing morphs and morphemes. Thus, the phonemically distinct English plural morphs /-s/, /-z/ and /-əz/ are classified together in the same morpheme on the basis of their complementary distribution in such words as cats, dogs, and foxes.

Perhaps because syntax is so far removed from the basic data, its position in a structural analysis is rather insecure.1 A structuralist asked to describe his methodology is likely to follow the course adopted here and concentrate on phonemics. A representative study of English syntax is that of Fries (1952) in which he ignores the problem of identifying syntactic elements (words) and uses substitution to categorize words into syntactic classes. His noun-like Class 1, for example, is defined on the occurrence of words in such environments as The _ was good. Sentences are then represented as sequences of word classes.

This description of structural methodology is offered to demonstrate that the role of semantics in this view of language is marginal at best. In the case of Bloomfield this was not a result of any lack of interest. In Language, for example, the remainder of the book contains many references to various semantic issues in historical and descriptive linguistics. There is, in fact, a good deal more emphasis on meaning in Bloomfield’s work than in the writings of later structuralists or in the work of Chomsky. Consider one of the comments in Language on the general goals of linguistic analysis:

Man utters many kinds of vocal noise and makes use of the variety: under certain types of stimuli he produces certain vocal sounds, and his fellows, hearing these same sounds, make the appropriate response. To put it briefly, in human speech, different sounds have different meanings. To study this co-ordination of certain sounds with certain meanings is to study language. (Language, 27)

This is not unlike the characterization of the goal of a linguistic description given by many of the writers in this present volume. The parallelism between various formal categories (phoneme, morpheme, etc.) and their semantic counterparts (sememe, episememe, etc.) is emphasized. Why, given this clear interest in semantic questions, does Bloomfield not incorporate meaning into the structural description of language? The answer seems to lie in his definition of meaning.

We have defined the meaning of a linguistic form as the situation in which the speaker utters it and the response which it calls forth in the hearer. The speaker’s situation and the hearer’s response are closely co-ordinated, thanks to the circumstance that every one of us learns to act indifferently as a speaker or as a hearer. In the causal sequence

speaker’s situation ------> speech ----> hearer’s response,

the speaker’s situation, as the earlier term, will usually present a simpler aspect than the hearer’s response; therefore we usually discuss and define meanings in terms of a speaker’s stimulus.

The situations which prompt people to utter speech, include every object and hap¬ pening in their universe. In order to give a scientifically accurate definition of meaning for every form of a language, we should have to have a scientifically accurate know¬ ledge of everything in the speaker’s world. (Language, 139)

Given such a global definition, one may rightly be pessimistic about the prospects of describing meaning in any systematic fashion. In more recent terminology, Bloomfield is equating meaning to the encyclopedia rather than to the dictionary. It is interesting that he does distinguish different types of meaning along these lines though he does not take the narrower definition to be the domain of linguistic theories as Katz and Fodor were later to do.

People very often utter a word like apple when no apple at all is present. We may call this displaced speech...A starving beggar at the door says Im hungry and the housewife gives him food: this incident, we say, embodies the primary or dictionary meaning of the speech-form Im hungry. A petulant child, at bed-time, says Im hungry, and his mother, who is up to his tricks, answers by packing him off to bed. This is an example of displaced speech. It is a remarkable fact that if a foreign observer asked for the meaning of the form Im hungry, both mother and child would still, in most instances, define it for him in terms of the dictionary meaning. . .The remarkable thing about these variant meanings is our assurance and our agreement in viewing one of the meanings as normal (or central) and the others as marginal (metaphoric or transferred). (Language, 141-2)

Differential meaning does function for Bloomfield as an essential part of the methodology of linguistics since the identification of phonemes is based on differences in meaning as determined by informant judgments.

These views, while they do anticipate many future developments in semantic analysis, signal the exclusion of semantics from linguistics and represent an important attempt to constrain the scope of linguistic theories in a way that will permit linguists to reach definite, though limited, goals. This rejection of meaning became even more complete in later theoretical works by structuralists. Zelig Harris, who is a significant transitional figure between structural and generative-transformational linguistics, attempted, in Methods of Structural Linguistics (1951), to specify the exact operations that were necessary to derive a linguistic description, operationally, from basic linguistic data. He accepted Bloomfield’s general position on the definition of meaning and the relations between form and meaning but denied that meaning could be used as anything more than an heuristic device in exact linguistic methodology. The rejection of meaning is seen in its most extreme form in Bloch (1948) where the human informant-judge is eliminated, and it is proposed that the input to a linguistic analysis need consist of nothing more than accurate recordings of utterances.

A consequence of restricting linguistics to purely formal matters was an extreme narrowness of focus on the utterances of a language independent of any properties of human language users. The external and internal stimuli acting on a speaker are placed outside of linguistics and all other, perhaps more interesting, aspects of human speakers are excluded as well. Further, the results of a linguistic analysis are not taken to be relevant to an understanding of the capacities and fundamental characteristics of human beings. The independence and methodological priority of form over meaning is clearly affirmed. This assumption, that form is independent, may be regarded as one of the central conceptions of modern linguistic theory, and, though it has come under increasingly severe attack in recent years, it continues to be vigorously defended by such scholars as Chomsky in this volume.

1 Harris (1951) includes a large part of what is normally regarded as syntactic analysis within his level of morphology and has no syntactic level as such. Figure 1 represents a guess as to what a separate syntactic component might contain. Words are classified by substitution and sentences are represented as sequences of word classes.

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي للقرآن الكريم يقيم جلسة حوارية لطلبة جامعة الكوفة

|

|

|