Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2025-03-17

Date: 2024-05-21

Date: 2024-03-27

|

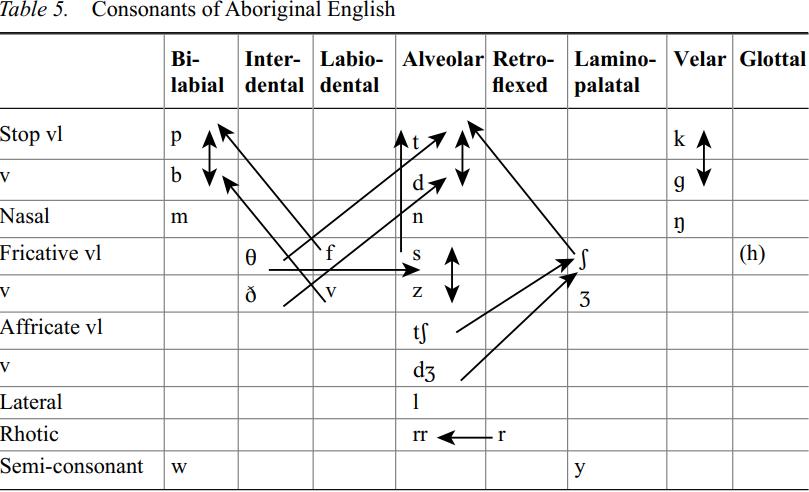

The inventory of consonants in Aboriginal English, and their distribution, show the influence of the pidgin/creole history of the dialect, although historic records show that many of the phonetic modifications which took place in the early stages of pidginization are no longer operating (Malcolm and Koscielecki 1997: 59). Table 5 represents the consonants of Aboriginal English, showing some of the common substitutions which take place:

Most of the consonants of Australian English, with the exception of /h/ in some cases, may be heard in Aboriginal English, but the phonemic boundaries of the latter are much more porous, with respect to voicing versus non-voicing, stop versus fricative articulation and alveolar versus lamino-palatal place of articulation.

There is clearly a preference for stop over fricative articulations. Bilabial, alveolar and velar stops are strongly in evidence, and often substitute for other sounds. The distinction between voiced and voiceless stops is not strongly maintained, with the general exception of when they are in the initial position (Flint 1968: 12; Alexander 1968; Sharpe 1976). There is a preference for voiceless stops except before nasals (Sharpe 1976: 13). Although the /t/ is represented on the chart as alveolar, in some communities it is dental (Flint 1968).

The labio-dental fricatives /f/ and /v/ are often replaced by stops, as in /pɔl/ ‘fall’ and /hæp/ ‘have’, though the substitution of the fricatives may be selective, as in /faɪp/ ‘five’ (Eagleson, Kaldor and Malcolm 1982: 82). The interdental fricatives /θ/ and /ð/ are highly vulnerable to substitution by alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/, as in most contact and non-standard forms of English. /θ/ may also become /s/, as in /nasɪŋ/ ‘nothing’. Sibilants are not always clearly distinguished and may be substituted for one another. This also affects the affricates /ʧ/ and /ʤ/ which may become /ʃ/. The status of the glottal fricative /h/ is unresolved in Aboriginal English. The tendency to remove it initially and medially is balanced by an equally strong tendency, at least in some areas, to add it initially where it does not occur in StE.

The nasals, which have counterparts in Aboriginal languages and creoles, generally occur as in StE, except for the common substitution of the allomorph /-an/ for /-ɪŋ/, as in /sɪŋan/ ‘singing’.

The Aboriginal English consonant inventory, in places where there is influence from Aboriginal languages and creole, includes a trilled variant of /r/, which may occur where /t/ comes between vowels, as in gorrit ‘got it’ and purrit ‘put it’ (Sharpe 1976: 15). In some places the variant is flapped rather than trilled, as in /hɪɾɪm/ ‘hit him’ or /ʃΛɾΛp/ ‘shut up’ (Eagleson, Kaldor and Malcolm 1982: 81).

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|