تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

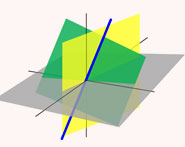

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 26-10-2015

Date: 17-1-2016

Date: 13-1-2016

|

Born: 27 February 1547 in Baalbek, now in Lebanon

Died: 30 August 1621 in Isfahan, Iran

Baha' al-Din al-Amili is also known as Sheykh Bahaee or Sheikh Bahai. His father, Shaykh Husayn ibn 'Abd al-Samad al-Amili, was a Shi'ite theologian who played a major role in his son's religious education. They lived in a region which had come under the rule of the Ottomans in 1517. The family, however, suffered persecution from the Ottomans and, in 1554, they escaped to Herat (now in Afghanistan) which was part of the Safavid Empire. Stewart writes that [6]:-

... the Shiite scholar Husayn ibn 'Abd al-Samad al-Amili wrote an eloquent letter-cum-travel account describing his experiences to his teacher Zayn al-Din al-Amili who had remained in Jabal 'Amil. ... [It] describes a journey that occurred earlier that same year. Husayn's statements do not spell out the exact cause of his flight from Ottoman territory but suggest that he was wary of being denounced to the authorities and felt that his academic career was severely limited there. He evidently supported Safavid legitimacy wholeheartedly, though he harboured misgivings about the moral environment in Iran and had sharp criticisms for Persian religious officials.

As well as living in Herat, al-Amili also spent much time in Isfahan, now in Iran. It was in Isfahan that he completed his education having excellent teachers of mathematics and medicine. In fact al-Amili's father held the position of Shaykh al-Islam, an honourific title given to the chief judge of the Muslim court of law, at Herat having been given this role by Shah Tahmasb (for details see [9]). At this time al-Amili was in Qazvin, the Safavid capital, both studying and teaching there. In 1575 his father came from Herat to the court in Qazvin to request permission for himself and his son to make a pilgrimage to Mecca. He was allowed to go but his son Baha al-Din al-Amili was not given permission so remained in Qazvin when his father left Herat later in 1575. His father died in 1576 but al-Amili did not replace him as Shaykh al-Islam in Herat (as some historians have claimed). Al-Amili's younger brother Abd al-Samad took over from his father while al-Amili became Shaykh al-Islam in Isfahan where he replaced his father-in-law Shaykh Ali al-Minshar who died in 1576. Stewart writes [7]:-

Baha al-Din al-Amili was an important religious authority in the Safavid Empire and held the high position of shaykh al-islam of the Safavid capital, Isfahan.

In fact at this time Isfahan was not the Safavid capital but only became that at a later time. In 1587 Shah Abbas I, at the age of fifteen, became the ruler of the Safavid Empire and brought in many reforms which strengthened the Empire's position, particularly enabling them to fight the Ottomans. The capital of the Safavid Empire had been at Qazvin but Shah Abbas I moved the capital to Isfahan in 1597. Al-Amili was still Shaykh al-Islam in Isfahan which then became the capital. When al-Amili was Shaykh al-Islam in Isfahan he travelled regularly with the royal court which was based in Qazvin.

Let us return to the period when al-Amili was in Qazvin. He had not been given permission to make the pilgrimage to Mecca with his father in 1575 but was given permission to make the pilgrimage in 1583. He visited Mecca in that year, and returned in the following year making visits to Cairo, Jerusalem, and Damascus on the way [10]:-

... he traveled in disguise ... While being detained by Ottoman customs officials on the way into Ottoman territory at Amid in 1583, he recorded that fate had disappointed him and separated him from his loved ones ...

By February 1585 he had reached Tabriz and was back in Isfahan later that year. In 1587 he was still in Isfahan for he completed a work on weights and measures there in that year [10]:-

Three years later, in 1590, he negotiated with Yuli Beg, the provincial governor who had rebelled against Shah Abbas and barricaded himself in the local fortress, also in Isfahan. It thus appears that he spent most of the period 1583-90 in Isfahan, away from court.

In playing such an important role in ending what was a civil war, al-Amili was in high favour with Shah Abbas. Also having proved his negotiating skills, Shah Abbas made use of him again in 1591 when he ran into difficulties in arranging a marriage between his son and the daughter of Khan Ahmad Gilani who ruled Gilan. This was, of course, a political marriage, but Khan Ahmad Gilani said he could not agree to the marriage since he had sworn an oath not to agree to any marriage for his daughter while she was a minor. Shah Abbas asked Sayyid Husayn al-Karaki and al-Amili to help him with this problem and they were able to show that Khan Ahmad Gilani's oath was not valid under Shi'ite law so the marriage could go ahead. By 1592, after the death of the Sayyid Husayn al-Karaki, al-Amili became the senior expert in the fields of law and religious education, so he became the Safavid Empire's senior jurist [10]:-

The death of Sayyid Husayn al-Karaki was a momentous event in Baha al-Din's career, the watershed which made him, at the age of forty-five, the leading jurist of the Empire.

We know that al-Amili moved frequently between the major cities of the Empire, for example in late 1594 he was in Qazvin, in February 1595 he was in Baghdad where he visited the shrine of the Kazimayn, but by June of that year he was back in Qazvin where he attended banquets Shah Abbas put on for scholars and students of religion as part of Ramadan. Around this time the poet al-Taluwi wrote (quoted in [10]):-

[Baha al-Din al-Amili] is now residing in Qazvin at the court of the King of Persia, Abbas. There, his word has the force of deed for the people, and he is held in the greatest esteem and respect by the elite and commoners alike, as travelers coming from that region have averred and as numerous reports to that effect have confirmed.

Al-Amili was an expert on a wide range of subjects such as theology, philosophy, law, and mathematics. He was famed as a poet, a grammarian and an architect. We will say a little about his contributions to this wide range of topics but we will concentrate on his contributions to mathematics and astronomy. Perhaps his most famous mathematical work was Quintessence of Calculation which was a treatise in ten sections, strongly influenced by The Key to Arithmetic (1427) by Jamshid al-Kashi.

Rofagha writes [2]:-

The study concludes the following: First, 'Quintessence of Calculation' was a highly influential mathematics textbook in Central Asia between the 17th century and the beginning of the 20th century. Its influence was partly due to the soundness of its mathematical algorithms resulting from Sheikh Bahai's mastery of mathematics, especially the one enhanced by al-Kashi, a celebrated mathematician in the 15th century. The study provides evidence that Sheikh Bahai studied al-Kashi's work. By utilizing these algorithms, Sheikh Bahai made the highly practical aspects of seven centuries of Islamic-culture mathematical achievements available to the region at large. Furthermore, the study concludes that the remarkable influence of 'Quintessence of Calculation' can be attributed to the specific approaches of Sheikh Bahai's presentations of mathematical concepts and algorithms. His approaches are identified as a result of detailed analytical comparison between this book and a major book of al-Kashi. The study also provides a partial answer to the creativity of Sheikh Bahai that enabled him to author several educational books, including 'Quintessence of Calculation', which were highly influential for several centuries. Subsequently, the study identifies Sheikh Bahai's method of discovery, which was also practiced by Avicenna (ibn Sina), a distinguished mathematician and scientist in the 11th century; this method is introduced and examined through a contemporary hypothesis presented by Elahi.

Other works on astronomy included: The Flat Surface, a work on the astrolabe; A Treatise on Astronomy; and, his most important astronomical work The Anatomy of the Heavens, a treatise in five sections which summarised the works of earlier authors. Among al-Amili's works on grammar we mention: The Secrets of Eloquence; All Eternal Directives respecting the Science of Arabic Grammar; and The Elevated Words, also an Arabic grammar. Among his religious works are: The Forty Hadith Compilation, an annotated compilation of forty traditions ascribed to the prophet Muhammad; The Orchards of Veracity in Commentary upon the Sahifa al-sajjadiyya; On the Science of Hadith-Tradition; Treatise on the Pilgrimage; Treatise on Fasting; Treatise on the Law of Obligatory Prayer; and Treatise on the Law of Ritual Prostration. Some of these works, as is evident from their titles, also consider legal aspects of religion. His other legal works include: The Dawning Place of the Two Suns and the Elixir of Twofold Felicity; Issues in Jurisprudence; The Treatise on Establishment of the Doctrines of the Shi'a, the legalistic aspects and the doctrinal fundamentals; Essence of the Foundations of Jurisprudence; and Treatise on the Determination of the Qibla. He was also famed as a poet writing: On the Secrets of the Mightiest Name of God; Bread and Halva, which describes the experiences of an itinerant holy man and this could well be autobiographical describing his own Mecca pilgrimage; Bread and Cheese; Mouse and Cat; Milk and Sugar; and The Parrot, containing 2500 verses.

Al-Amili had several students, the most famous being Molla Sadra who became the pre-eminent philosopher of Shi'ite Islam.

An interesting discovery was made comparatively recently in Isfahan when the house in which al-Amili lived was identified. It has been restored and a conducted tour of the house is available on the web, see [4].

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|