Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-09-19

Date: 2023-10-31

Date: 2023-10-28

|

Gates and burgers

The creative potential of derivational resources is such that affixes may emerge from the most unlikely sources. At the time of writing the UK government was embroiled in a difficulty labelled ‘Plebgate’ in the popular press, in which the suffix -gate was attached to the derogatory term ‘pleb’ (plebeian). This followed Irangate, Sachsgate, Bigotgate, Debategate, Dianagate and numerous other ‘-gates’ in which a scandal, and the subsequent alleged cover-up, have made headline news.

There’s no connection, obviously, between ‘gate’ meaning ‘opening or door’ and the notion of scandal or cover-up, but the association was cemented by the Watergate bugging scandal which eventually brought down US President Richard Nixon in 1973, since when the suffix ‘gate’ has been applied to any number of scandals. Plebgate involved accusations that a minister called a police officer a pleb in Downing Street when told he was not allowed to take his bicycle through the Downing Street gate, which led to the affair being dubbed, perhaps inevitably, Gategate by some commentators.

The suffix burger has a longer history, and is based on a false derivation ham+burger. In fact, as any schoolchild knows, hamburgers contain beef, not ham, and the original derivation in German was Hamburg+er, ‘native of Hamburg’, and by extension the hot snack associated with that city. But the misderivation has spawned a range of new lexemes, including cheeseburger, veggieburger, chickenburger and beanburger.

English generally does not use infixes, inserted within words, but there are some informal expletive or emphatic uses, e.g. a-whole-nother story, abso-bloody-lutely. In Russian, the verbal infix -vy- carries the nuance that an action happens on a regular basis, e.g. arestovac (to arrest); arestovyvac (to arrest repeatedly). Note that these affixes are subject to selectional restrictions: un-, for example (see Spotlight on previous page), can be used with adjectives (unclear, unreasonable) and verbs (unfasten, undo), but not with nouns (barring one or two marginal exceptions, such as unconcern). The comparative and superlative suffixes -er and -est can normally only be used with gradable antonyms (e.g. warm-warmer-warmest, but not pregnant-*pregnanter-*pregnantest), and not with adjectives of more than two syllables (*marvellouser, *incrediblest).

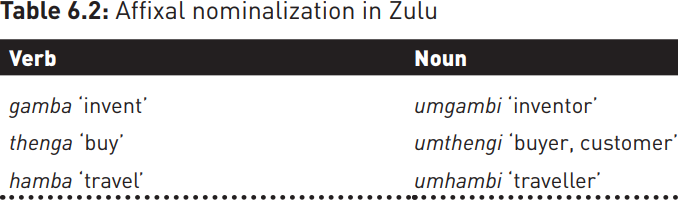

Prefixes in English, unlike suffixes, almost never change word class: there are a few, generally unproductive, exceptions such as a- which derives the adjectives ablaze, awash and abuzz from the nouns blaze, wash and buzz, and the verbal prefix en- in enrage, enamour, entangle. Not all languages restrict the functions of prefixes in this way. In Zulu, for example, the prefix um-, coupled with a change of final vowel, is used to derive nouns from verbs:

In polysynthetic languages, strings of bound morphemes can be combined to form words which would correspond to clauses or sentences in languages such as English, as in this example from the Australian language Tiwi.

In the case of compounding, the elements combined are free rather than bound morphemes, but the meaning is often not reducible to that of the combined elements. Examples from English include freefall (vb), double-dip (adj.), firewall (n.), but Germanic languages are well known for using compounds to a much greater degree than would be acceptable in English, for example Swedish järnvägsstation (literally ‘iron way’s station’) ‘railway station’, or German Arbeitsbeschaffungsmaßnahme (literally ‘work creation measure’) ‘job creation scheme’.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|