Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-08-29

Date: 2023-08-18

Date: 2023-04-04

|

None of the Secondary-A verbs have any independent semantic roles. Basically, they modify the meaning of a following verb, sharing its roles and syntactic relations.

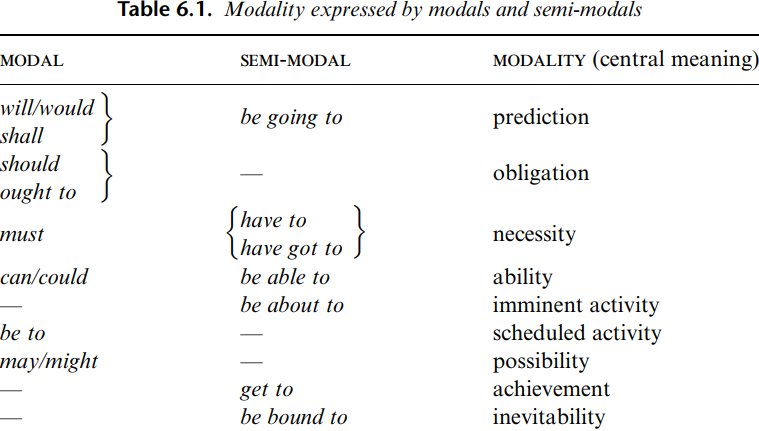

As stated, the basic choice for a non-imperative clause (a statement or a question) is between realis, referring to some action or state which has reality, and irrealis, something which is uncertain in the future or was unrealized in the past. There are nine modalities within irrealis, each realized by a secondary verb. There are two syntactically different but semantically related types, MODALS and what we can call SEMI-MODALS, which express the modalities. The main MODALS, and the SEMI-MODALS, (As mentioned that, will, would, shall, should, can, could and must are typically pronounced as clitics.) Many tens of thousands of words have been written about the English modals. Only some of the main points of their grammatical and semantic behavior are indicated here.

It was mentioned that a clause may contain a chain of verbs, each in syntactic relation with its neighbors, e.g. She will soon be able to begin telling John to think about starting to build the house. A modal must occur initially in such a chain—that is, it cannot be preceded by any other verb. Semi-modals behave like other Secondary verbs in that they can occur at the beginning or in the middle of a chain, but not at the end. A VP can contain only one modal, but it may involve a sequence of semi-modals, e.g. He has to be going to start writing soon.

A semi-modal can occur in initial position; it does not then have exactly the same import as the corresponding modal. Semi-modals often carry an ‘unconditional’ sense, while modals may indicate prediction, ability, necessity, etc. subject to certain specifiable circumstances. Compare:

(1a) My sister will get married on Tuesday if I go home on that day

(1b) My sister is going to get married on Tuesday, so I’m going home on that day

(2a) John can do mathematics, when he puts his mind to it

(2b) John is able to do mathematics, without even having to try

(3a) The boat must call tomorrow, if there aren’t any high seas

(3b) The boat has to call tomorrow, even if there are high seas

However, this is very much a tendency; there is a great deal of semantic overlap between the two sets of verbs.

A semi-modal may substitute for a corresponding modal in a syntactic context where a modal is not permitted—for example, I assume John to be able to climb the tree, alongside I assume that John can climb the tree (since a TO complement cannot include a modal).

The first word of the auxiliary component of a VP plays a crucial syntactic role in that it takes negator not  n’t, and is moved before the subject in a question. Modals (the ought and be elements in the case of ought to and be to) fulfil this role, e.g. Will he sing?, He shouldn’t run today, Are we to go tomorrow? When a semi-modal begins a VP then the be of be going to, be able to, be about to, and be bound to and the have of have got to will take the negator and front in a question, e.g. Is he going to sing?, You haven’t got to go. The have of have to behaves in the same way in some dialects, e.g. Has he to go? He hasn’t to go; but other dialects include do (effectively treating have to as a lexical verb in this respect, and not as an auxiliary), e.g. Does he have to go?, He doesn’t have to go. The get of get to never takes the negator or fronts in a question—one must say I didn’t get to see the Queen, not *I getn’t to see the Queen.

n’t, and is moved before the subject in a question. Modals (the ought and be elements in the case of ought to and be to) fulfil this role, e.g. Will he sing?, He shouldn’t run today, Are we to go tomorrow? When a semi-modal begins a VP then the be of be going to, be able to, be about to, and be bound to and the have of have got to will take the negator and front in a question, e.g. Is he going to sing?, You haven’t got to go. The have of have to behaves in the same way in some dialects, e.g. Has he to go? He hasn’t to go; but other dialects include do (effectively treating have to as a lexical verb in this respect, and not as an auxiliary), e.g. Does he have to go?, He doesn’t have to go. The get of get to never takes the negator or fronts in a question—one must say I didn’t get to see the Queen, not *I getn’t to see the Queen.

Each modal has a fair semantic range, extending far beyond the central meanings we have indicated (they differ in this from the semi-modals, which have a narrower semantic range). There is in fact considerable overlap between the modals (see the diagram in Coates 1983: 5). The central meaning of can refers to inherent ability, e.g. John can lift 100 kilos (he’s that strong), and of may to the possibility of some specific event happening, e.g. We may get a Christmas bonus this year. But both verbs can/may refer to a permitted activity, e.g. John can/may stay out all night (his mother has said it’s all right) and to some general possibility, e.g. The verb ‘walk’ can/may be used both transitively and intransitively.

It is usually said, following what was an accurate analysis in older stages of the language, that four of the modals inflect for tense, as follows:

A main justification for retaining this analysis comes from back-shifting in indirect speech. Recall that a sentence uttered with present tense is placed in past tense when it becomes indirect speech to a SPEAKING verb in past tense, e.g. ‘I’m sweating,’ John said and John said that he was sweating.

We do get would, could and might functioning as the back-shift equivalents, in indirect speech, of will, can and may, e.g. ‘I will/can/may go,’ he said and He said that he would/could/might go. Shall and should now have quite different meanings and the back-shift version of shall, referring to prediction, is normally would (as it is of will and would) while the back-shift version of should, referring to obligation, is again should. There is discussion of back-shifting for modals and semi-modals.

Would, could and might nowadays have semantic functions that go far beyond ‘past tense of will, can and may’. Whereas will, can and may tend to be used for unqualified prediction, ability and possibility, would, could and might are employed when there is some condition or other qualification. For example:

(4a) You will find it pleasant here when you come

(4b) If you come, you would find it pleasant here

(5a) You can borrow the car when you come

(5b) If you come, you could borrow the car

(6a) I may bake a cake

(6b) I might bake a cake if you show me how

In addition, would can mark a ‘likely hypothesis’, e.g. ‘I saw John embrace a strange woman.’ ‘Oh, that would be his sister.’ Could is often a softer, more polite alternative to can—compare Could you pass the salt? and Can you pass the salt? (in both cases what is literally a question about ability is being used as a request). And only may (not might) can substitute for can in a statement of possibility.

There is a clear semantic difference between the ‘necessity’ forms must/ has to/has got to and the ‘obligation’ forms should/ought to:

(7a) I should/ought to finish this essay tonight (but I don’t think I will)

(7b) I must/have to/have got to finish this essay tonight (and I will, come what may)

It is hard to discern any semantic difference between should and ought to, these two modals being in most contexts substitutable one for the other (see the discussion in Erades 1959/60, Coates 1983: 58–83). However, ought to is a little unwieldy in negative sentences—where the ought and the to get separated—so that should may be preferred in this environment; thus You shouldn’t dig there seems a little more felicitous than You oughtn’t to dig there (although the latter is still acceptable). The same argument should apply to questions, where ought and to would again be separated; interestingly, the to may optionally be dropped after ought in a question, e.g. Ought I (to) go?

A modal cannot be followed by another modal, although a semi-modal can be followed by a semi-modal, as in is bound to be about to. Generally, any modal may be followed by any semi-modal; for example, will be able to and could be about to. A notable exception is the modal can, which may not be followed by a semi-modal, could being used instead, as in He could be about to win, She could be going to lose. Have to and have got to are stylistic variants, but after a modal only have to is possible; for example, He will have to go, not *He will have got to go. And, because of their meanings, the sequence be to followed by be bound to is unacceptable.

Parallel modals and semi-modals from the two columns can be combined—will be going to could refer to ‘future in future’, e.g. He will be going to build the house when he gets planning permission (but even then I doubt if he’ll do it in a hurry), while could be able to combines the ‘possibility’ sense of could (as in That restaurant could be closed on a Sunday) with the ‘ability’ meaning of be able to, e.g. John could be able to solve this puzzle (let’s ask him).

There are a few other verbs that have some of the characteristics of modals. Used to must be first in any chain of verbs but—unlike other modals—it generally requires do in questions and negation, e.g. Did he use(d) to do that?, He didn’t use(d) to do that (although some speakers do say Used he to do that? and He use(d)n’t to do that). It could be regarded as an aberrant member of the MODAL type.

Then there is had better, as in He had better go. Although the had is identical with the past tense of have, had better is used for any time reference, and without any inflection for person of subject (coinciding in this with all modals except be to); it can also be used where a past form would be expected in indirect speech, e.g. I told him he had better go. Sometimes the had is omitted—You better (not) go! This is perhaps another, rather unusual, modal.

Need (from the WANTING type) and dare (from DARING) have two patterns of syntactic behavior. They may be used as lexical verbs, with a TO complement clause, taking the full set of inflections for tense, including 3sg subject present ending -s, and requiring do in questions and negatives if there is no other auxiliary element present, e.g. Does he dare/need to go?, He doesn’t dare/need to go. But these may also be used as modals (with no to), fronting in questions and taking the negative directly, e.g. Dare/Need he go?, He daren’t/needn’t go. Note that in their modal use dare and need do not take the 3sg present inflection -s (behaving like all modals except be to) but they also lack a past tense form (like must but unlike will, can, may). There is a semantic contrast between the two uses of need and dare because of this, the modal uses are almost restricted to questions and negatives.

As we mentioned, there is a special use of go and come, followed by a lexical verb in -ing form, that is grammatically a little like a modal, as in Let’s go fossicking.

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|