Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 19-1-2023

Date: 2023-11-30

Date: 10-1-2023

|

The discussion shows how (in a phase-based theory of syntax in which CPs and transitive vPs are phases) theoretical considerations force successive-cyclic wh-movement through spec-CP and spec-vP. However, an interesting question which arises is whether there is any empirical evidence in support of the successive-cyclic analysis. As we shall see, there is in fact considerable evidence in support of such an analysis. We will look at evidence in support of successive-cyclic movement through spec-CP, we examine evidence of successive-cyclic movement through spec-vP.

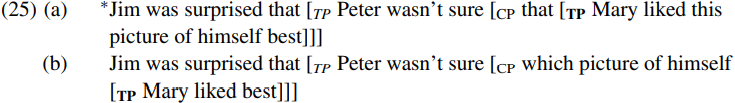

Let’s begin by looking at evidence from English. Part of the evidence comes from the interpretation of reflexive anaphors like himself. As we saw in exercise 3.2, these are subject to Principle A of Binding Theory which requires an anaphor to be locally bound and hence to have an antecedent within the TP most immediately containing it. This requirement can be illustrated by the contrast in (25) below:

In (25a), the TP most immediately containing the reflexive anaphor himself is the bold-printed TP whose subject is Mary, and since there is no suitable (third-person-masculine-singular) antecedent for himself within this TP, the resulting sentence violates Binding Principle A and so is ill-formed. However, in (25b) the wh-phrase which picture of himself has been moved to the specifier position within the bracketed CP, and the TP most immediately containing the reflexive anaphor is the italicized TP whose subject is Peter. Since this italicized TP does indeed contain a c-commanding antecedent for himself (namely its subject Peter), there is no violation of Principle A if himself is construed as bound by Peter – though Principle A prevents Jim from being the antecedent of himself.

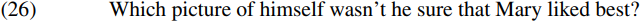

In the light of this restriction, consider the following sentence:

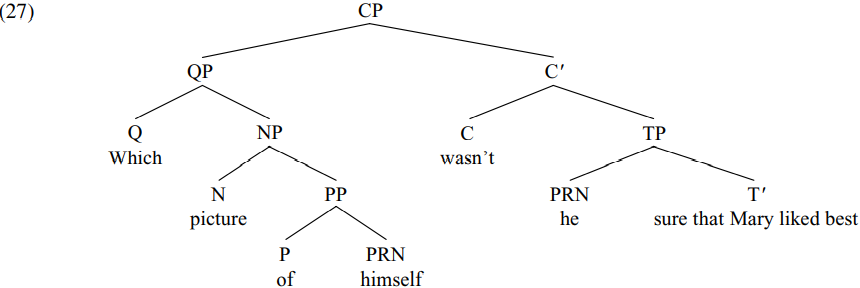

In (26), the antecedent of himself is he – and yet himself is clearly not c-commanded by he, as we see from (27) below (simplified, and showing only overt constituents):

In fact, the only elements c-commanded by the pronoun he in (27) are T-bar and its constituents. But if he does not c-command himself in (27), how come he is interpreted as the antecedent of himself when we would have expected such a structure to violate Principle A of Binding Theory and hence to be ill-formed?

We can provide a principled answer to this question if we suppose that wh-movement operates in a successive-cyclic fashion, and involves an intermediate stage of derivation represented in (28) below (simplified by showing overt constituents only):

(Note that (28) is an intermediate stage of derivation, not a complete sentence structure; if it were a sentence, in relevant varieties it would violate the Multiply Filled Comp Filter) In (28), the anaphor himself has a c-commanding antecedent within the italicized TP most immediately containing it – namely the pronoun he. If we follow Belletti and Rizzi (1988), Uriagereka (1988) and Lebeaux (1991) in supposing that the requirements of Principle A can be satisfied at any stage of derivation, it follows that positing that a sentence like (26) involves an intermediate stage of derivation like (28) enables us to account for why himself is construed as bound by he. More generally, sentences like (26) provide us with evidence that long-distance wh-movement involves successive cyclic movement through intermediate spec-CP positions – and hence with evidence that CP is a phase. (See Fox 2000 and Barss 2001 for more detailed discussion of related structures.) At a subsequent stage of derivation, the wh-QP which picture of himself moves into spec-CP in the main clause, so deriving the structure (27) associated with (26) Which picture of himself wasn’t he sure that Mary liked best?

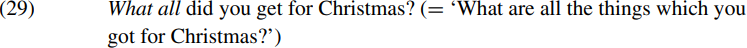

A further argument for successive-cyclic wh-movement through spec-CP (and consequently for the phasehood of CP) is offered by McCloskey (2000), based on observations about quantifier stranding/floating in West Ulster English. As we saw, in this variety, a wh-word can be modified by the universal quantifier all, giving rise to questions such as:

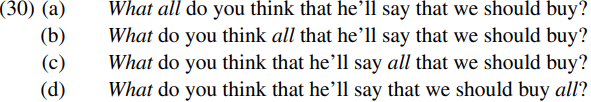

McCloskey argues that in such sentences, the quantifier and the wh-word originate as a single constituent. He further maintains that under wh-movement, the wh-word what can either pied-pipe the quantifier all along with it as in (29) above, or can move on its own leaving the quantifier all stranded. In this connection, consider the sentences in (30) below:

McCloskey claims (2000, p. 63) that ‘All in wh-quantifier float constructions appears in positions for which there is considerable independent evidence that they are either positions in which wh-movement originates or positions through which wh-movement passes. We have in these observations a new kind of argument for the successive-cyclic character of long wh-movement.’

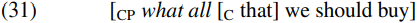

McCloskey argues that the derivation of (30a–d) proceeds along the following lines (simplified in a number of ways). The quantifier all merges with its complement what to form the structure [all what]. The wh-word what then raises to become the specifier of all, forming the overt QP [what all]. (An incidental detail to note here is that this part of McCloskey’s analysis violates the Remerger Constraint which we posited to the effect that ‘No constituent can be merged more than once with the same head.’ One way of getting round this is to suppose that what moves to a spec-DP position above QP, rather than to spec-QP. However, we shall ignore this detail in what follows.) The resulting QP [what all] is merged as the object of buy, forming [buy what all]. If what undergoes wh-movement on its own in subsequent stages of derivation, we derive (30d) ‘What do you think that he’ll say that we should buy all?’ But suppose that the quantifier all is pied-piped along with what under wh-movement until we reach the stage shown in skeletal form below:

If wh-movement then extracts what on its own, the quantifier all will be stranded in the most deeply embedded spec-CP position, so deriving (30c) ‘What do you think that he’ll say all that we should buy?’ By contrast, if all is pied-piped along with what until the end of the intermediate CP cycle, we derive:

If wh-movement then extracts what on its own, the quantifier all will be stranded in the intermediate spec-CP position and we will ultimately derive (30b) ‘What do you think all that he’ll say that we should buy?’ But if all continues to be pied-piped along with what throughout the remaining stages of derivation, we ultimately derive (30a) ‘What all do you think that he’ll say that we should buy?’

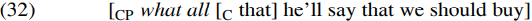

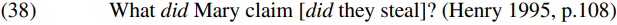

There is also considerable empirical evidence in support of successive-cyclic movement through spec-CP from a number of other languages. One such piece of evidence comes from preposition pied-piping in Afrikaans. Du Plessis (1977, p. 724) notes that in structures containing a wh-pronoun used as the complement of a preposition in Afrikaans, a moved wh-pronoun can either pied-pipe (i.e. carry along with it) or strand (i.e. leave behind) the preposition – as the following sentences illustrate:

Du Plessis argues that sentences such as (33c) involve movement of the PP waar-voor ‘what-for’ to spec-CP position within the bracketed complement clause, followed by movement of waar ‘what’ on its own into the main-clause spec-CP position, thereby stranding the preposition in the intermediate spec-CP position. On this view, sentences like (33c) provide empirical evidence that long-distance wh-movement involves movement through intermediate spec-CP positions.

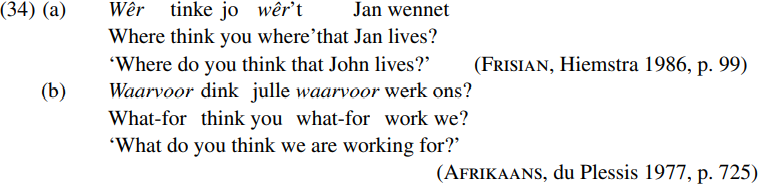

A rather different kind of argument for successive-cyclic wh-movement comes from the phenomenon of wh-copying. A number of languages exhibit a form of long-distance wh-movement which involves leaving an overt copy of a moved wh-pronoun in intermediate spec-CP positions – as illustrated by the following structures cited in Felser (2001):

In cases of long-distance wh-movement out of more than one complement clause, a copy of a moved wh-pronoun appears at the beginning of each clause – as illustrated by (35) below:

The wh-copies left behind at intermediate landing sites in sentences such as (34) and (35) suggest that long-distance wh-movement involves movement of the wh-expression through intermediate spec-CP positions – precisely as a phase-based theory of syntax would lead us to expect. (See Nunes 2001 for further discussion.)

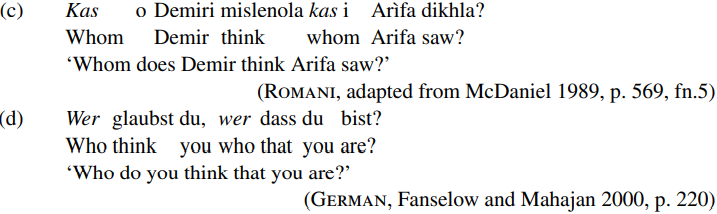

A parallel wh-copying phenomenon is reported in an intriguing study of the acquisition of wh-questions by Ros Thornton (1995). She reports children producing long-distance wh-copy questions such as the following (1995, p. 147)

In such cases, the bold-printed wh-word moves to the front of the overall sentence, but leaves an italicized copy at the front of the bracketed complement clause. What this suggests is that wh-movement involves an intermediate step by which the wh-expression moves to spec-CP position within the bracketed complement clause before moving into its final landing site in the main-clause spec-CP position. The error made by the children lies in not deleting the italicized medial trace of the wh-word. Of course, this raises the question of why the children don’t delete the intermediate wh-word. One answer may be that the null complementizer heading the bracketed complement clause is treated by the children as being a clitic which attaches to the end of its specifier (just as have cliticises to its specifier in Who’ve they arrested?). Leaving an overt wh-copy of the pronoun behind provides a host for the clitic wh-complementizer to attach to. Such an analysis seems by no means implausible in the light of the observation made by Guasti, Thornton and Wexler (1995) that young children produce auxiliary-copying negative questions such as the following (the names of the children and their ages in years;months being shown in parentheses):

If we assume that contracted negative n’t is treated by the children as a PF enclitic (i.e. a clitic which attaches to the end of an immediately preceding auxiliary host in the PF component), we can conclude that the children spell out the trace of the inverted auxiliary did in order to provide a host for the enclitic negative n’t. More generally, data like (37) suggest that children may overtly spell out traces as a way of providing a host for a clitic.

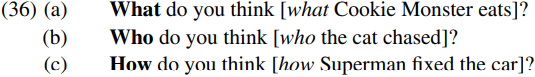

A related phenomenon is reported by Alison Henry in her (1995) study of Belfast English. She notes that in main-clause wh-questions in Belfast English, not only the main-clause C but also intermediate C constituents show T-to-C movement (i.e. auxiliary inversion), as illustrated below:

We can account for auxiliary inversion in structures like (38) in a straightforward fashion if we suppose that (in main and complement clauses alike in Belfast English) a C which attracts an interrogative wh-expression also carries an affixal [TNS] feature triggering auxiliary inversion. In order to explain auxiliary inversion in the bracketed complement clause in (38), we would then have to suppose that the head C of CP carries [WH, EPP] features which trigger movement of the interrogative pronoun what through spec-CP, given our assumption that C has an affixal [TNS] feature triggering auxiliary inversion in clauses in which C attracts an interrogative wh-expression. On this view, the fact that the complement clause shows auxiliary inversion provides evidence that the preposed wh-word what moves through the spec-CP position in the bracketed complement clause before subsequently moving into the main-clause spec-CP position.

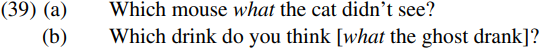

Returning now to wh-questions produced by young children, it is interesting to note that a further type of structure which Ros Thornton (1995) reports one of the children in her study (= AJ) producing are wh-questions like (39) below:

Here, the italicized C positions are filled by what – raising the question of why this should be. Thornton notes that a number of the children in her study also produced questions like:

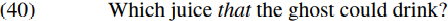

This suggests that what in structures such as (39) is a wh-marked variant of that. More specifically, it suggests that (for children like AJ) the complementizer that is spelled out as what when it carries [WH, EPP] features and attracts a wh-marked goal to move to spec-CP.

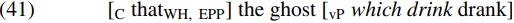

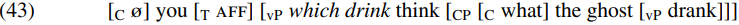

In the light of this assumption, let’s now look at how wh-movement applies in the derivation of (39b). Since the bracketed complement clause is transitive in (39b) and a transitive vP is a phase, the wh-phrase which drink will move to spec-vP on the embedded clause vP cycle. Thus, at the stage when the complementizer that enters the derivation, we will have the overt structure below (a structure which is simplified by omitting all null constituents, including traces):

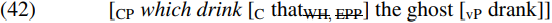

The complementizer that has [WH, EPP] features and consequently attracts which drink to move to spec-CP, so deriving the overt structure shown in simplified form below:

On the assumption that children like AJ spell out that as what when it carries the features [WH, EPP], the complementizer that will ultimately be spelled out as what. (By contrast, in standard varieties of adult English, the complementizer is always spelled out as that, irrespective of whether it is wh-marked or not.)

The next stage in the movement of the wh-phrase takes place on the main-clause vP phase, when which drink moves to spec-vP. At the point where the null complementizer heading the main clause is introduced into the derivation, we will have the following skeletal structure (with AFF denoting a tense affix, and the structure simplified by not showing trace copies or empty categories other than the main-clause C and T):

The null main-clause complementizer has a strong [TNS] feature which triggers raising of the tense affix to C. It also has [WH, EPP] features which trigger movement of which drink to spec-CP, so deriving (44) below (with do-support providing a host for the tense affix in the PF component):

On this view, the fact that the complementizer that is spelled out as what in (39b) provides evidence that wh-movement passes through the intermediate spec-CP position.

A more general conclusion which can be drawn from our discussion of (39) is that wh-marking of a complementizer provides us with evidence that the relevant complementizer triggers wh-movement (and indeed it may be that what in non-standard comparatives like Yours is bigger than what mine is has the status of a complementizer which triggers wh-movement of a null wh-operator). In this connection, it is interesting to note that McCloskey (2001) argues that long-distance wh-movement in Irish triggers wh-marking of intermediate complementizers. The complementizer which normally introduces finite clauses in Irish is go ‘that’, but in (relative and interrogative) clauses involving wh-movement we find the wh-marked complementizer aL (below glossed as what) – as the following long-distance wh-question shows:

(Note that the word order in (45) is wh-word+complementizer+verb+ subject+complement.) McCloskey argues that the wh-marking of each of the italicized complementizers in (45) provides evidence that wh-movement applies in a successive-cyclic fashion, with each successive C which is introduced into the derivation having [WH, EPP] features which trigger wh-marking of C and wh-movement of the relevant wh-expression. Chung (1994) provides parallel evidence from wh-marking of intermediate heads in Chamorro. The work of McCloskey and Chung provides further evidence that a complementizer is only wh-marked if it carries both a [WH] feature and an [EPP] feature.

Overall, then, we see that there is a considerable body of empirical evidence which supports the hypothesis that long-distance wh-movement is successive-cyclic in nature and involves movement through intermediate spec-CP positions. Additional syntactic evidence comes from partial wh-movement in a variety of languages (see e.g. Cole 1982, Saddy 1991 and Cole and Hermon 2000), and from exceptional accusative case-marking by a higher transitive verb of the wh-subject of a lower finite clause (reported for English by Kayne 1984a, p. 5 and for Hungarian by Bejar and Massam 1999, p. 66).

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|