Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 21-5-2022

Date: 2023-06-09

Date: 24-2-2022

|

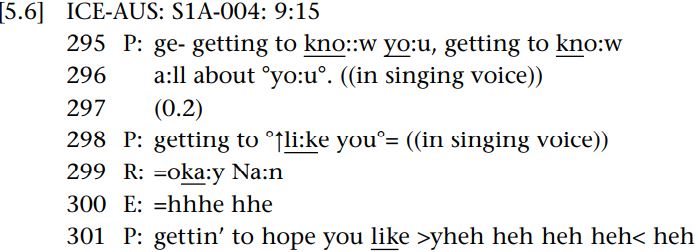

In a recent study, LaMarre, Landreville and Beam (2009) examined how irony used by American political satirist Steven Colbert (from “The Colbert Report”, which plays on the “Comedy Channel”) is interpreted by people with different political leanings. Colbert’s irony is ambiguous in that he uses deadpan satire, leaving it somewhat open to the viewer to decide who he is mocking (a point to which shall return). In one episode of the show in question, which played in 2006, Colbert was interviewing a radio talk show host, Amy Goodman, who is a well-known liberal associated with the Democracy Now! Movement. In the show Colbert introduced Goodman as a “super liberal lefty”, and then went on to claim the Iraq war is “breaking down conservative and liberal lines” and that “the conservatives are ‘right’ and the liberals are ‘wrong’ ” and so on (LaMarre et al. 2009: 220). Participants who identified themselves as ranging from “very liberal” through to “very conservative” were invited to watch the three-minute interview clip. It was found that while viewers of all political leanings agreed that Colbert was funny, “conservatives were more likely to report that Colbert only pretends to be joking and genuinely meant what he said, while liberals were more likely to report that Colbert used satire and was not serious when offering political statements” (2009: 212). In other words, we have a case here of multiple recipient understandings of speaker meaning. It is evident, then, that no matter what intent Colbert might have, “people will potentially see what they want to see” (2009: 229). Gibbs (2012) suggests that Colbert does not intend his irony to be necessarily understood by all, which further supports our view that in many cases we need to examine speaker meaning from multiple recipient positions.

An audience is a particular kind of reception role that combines characteristics of ratified and unratified participants (cf. Goffman 1981). On the one hand, an audience is expected to be able to hear clearly (and so is ratified), but on the other hand, an audience may not be in the sight of the speaker in the case of television or radio audiences, or may not receive any overt signal of recognition from speakers in the case of theatre audiences (and so are unratified) (Dynel 2011). This is because an audience is not always co-present despite being a ratified participant. The participation framework for recipients is thus also much more complex than the term “hearer” allows for, a point we will return to.

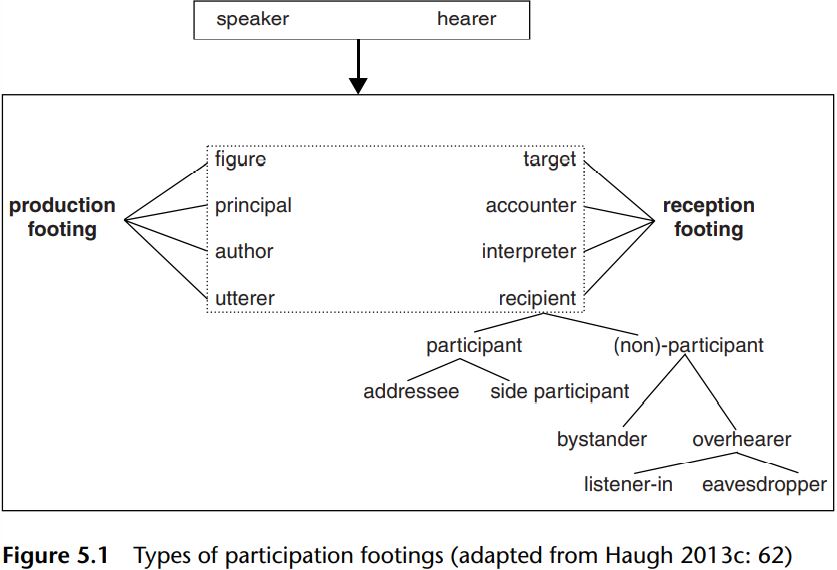

The layering of pragmatic meanings, which we can see in example [5.5], alludes to one point that was somewhat neglected by Goffman in his account of footing. As Goodwin and Goodwin (2004) argue, there remains a marked asymmetry between the rich cognitive and linguistic capabilities attributed to the speaker in the guise of production roles, and the cognitively and linguistically simple role attributed to recipients, whose participation status is determined primarily by the speaker. We propose here that reception roles should be attributed an equivalent degree of cognitive complexity to production roles (see also Haugh 2013c). The production role of animator (or utterer), who articulates talk, needs to be complemented by the different footings of the recipient (or recipients) who hear, and in most cases listen, to the talk. The role of the author who constructs the talk has a counterpart in the interpreter (or interpreters) who develop (multiple) representations of the meaning of this talk. The role of the principal who is socially responsible for those meanings is necessarily matched by the accounter (or accounters) who (explicitly or tacitly) hold the principal responsible. And finally, the production role of figure, namely the character who is depicted in the talk, is also a potential target when the character depicted is co-present or when an utterance is attributed to someone other than the speaker.

We can observe the importance of taking into account these different recipient footings when we examine cases of teasing, which can be seen as joking in some instances, but as annoying, goading or even bullying the target in other cases. Interactants can thus invoke these different recipient footings in such instances. Consider the following excerpt from a recording of a conversation taken from the Australian component of the International Corpus of English. In the conversation so far, Eddie has been talking about his new friend over dinner with his sister, Shelley, his mother, Beryl, and his grandparents, Patty and Roger. This excerpt begins with Eddie’s grandmother Patty teasing Eddie about his new friend by singing lyrics from the song, “Getting to know you” (which is from the Rogers and Hammerstein musical, “The King and I”).

While Eddie is clearly the target of the jocular mockery, and possibly the addressee, the other four participants, apart from Eddie, take recipient roles as side participants. And, although all five participants take interpreter footings, it is notable that it is in fact Roger, a side participant, who explicitly takes the footing of accounter when he implicates that Patty might be taking the mockery too far through a recognizable sequence-closing device, namely, okay (Beach 1995), rather than the target and likely addressee, Eddie. We will return to consider the interpersonal implications of teasing.

The complex array of footings we have discussed thus far are summarized in Figure 5.1. The assumption that speaker meaning is simply a matter of what a particular speaker intended and/or what the hearer thinks the speaker intended can only be maintained by focusing exclusively on two-party conversations, where the complex array of participant footings (illustrated above) tends to coalesce into what we intuitively think of as speakers and hearers (although not always). While multi-party conversations are an obvious place where numerous participant footings may arise, and thus where multiple understandings of speaker meaning are even more likely to arise, computer-mediated communications between multiple parties, and online social networking sites and the like, are also where an analysis of speaker meaning can benefit from a consideration of participation footings.

The use of the copy field in email messages sent in the workplace can be used to demonstrate this point. Skovholt and Svennevig (2006), for instance, show how “copying in” superordinates when making a request via email can be used to increase pressure on the recipients to get something done.

In the following excerpt, a systems operator (Geir Johnsen) is following up on getting the information that his superordinate (Line Myhre) had indirectly requested that another superordinate (Arvid Lervik) provide.

Geir reminds Arvid of the original request from Line by appending the prior messages to the email. By copying Line into the email sent to Arvid, Geir implicates that the delay in getting the information to Line is due to the lack of response from Arvid, and thus the responsibility for this delay does not lie with him. Geir could also be implicating that he would like Line to take responsibility for the situation (i.e. Arvid’s lack of response), especially given that Arvid is also Geir’s superordinate. In this case, while Arvid is the addressee and Line is positioned as a side participant, much of what is implicated here is in fact directed at Line, which serves to increase the pressure on Arvid to comply with the request. In other words, the witnessing of this email by another participant alters the pragmatic meanings that can be attributed to it. Through the various examples we have discussed, we can see how the footings summarized in Figure 5.1 are themselves created through talk. Footings can shift during interaction and, in some cases, speakers may even exploit the porous boundaries between different footings (see, for example, Goodwin 2007).

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي ينظّم ندوة حوارية حول مفهوم العولمة الرقمية في بابل

|

|

|