Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 17-5-2022

Date: 30-4-2022

Date: 1-6-2022

|

Linguistic under-determinacy and what is literally said

One of the key challenges facing neo-Gricean accounts of speaker meaning concerns Grice’s stipulation that what is said should be constrained by the particular elements of a sentence, including their order and syntactic character. These accounts argue that this is too strict, because what speakers are taken to say2 is under-determined by linguistic forms. In other words, “filling in the boxes” provided by the words and syntactic structure through disambiguating sense, assigning reference, and resolving indexicals of the utterance via inference does not match with what we would generally understand a speaker to be saying2. Linguistic under-determinacy is thus a critical problem because we normally understand what is said2 to have both logical properties (i.e. it can enter into entailment or contradiction relations) and truth conditional properties (i.e. it can be evaluated against real world relations). And yet, without such logical and truth-conditional properties it is difficult to maintain a distinction between what is said and what is implicated.

While this issue is still being debated amongst neo-Griceans, most have opted to defend a strictly literal notion of what is said, which is then supplemented with further levels of pragmatic meaning representations.4 It is argued that a strictly literal notion of what is said is necessary in order to maintain the intuition of ordinary users that a literal meaning representation that is tightly aligned with what is said1 is potentially available, even though we might not access it in normal circumstances (Bach 2001; Terkourafi 2010). Bach (2001: 17), for instance, proposes the Syntactic Correlation constraint, namely, “that every element of what is said correspond to some element of the uttered sentence”. Notably, a literal notion of what is said is even more restricted than the definition of saying originally proposed by Grice, as it does not include reference assignment, unless it can be worked out from readily contextual information independent of the speaker’s intentions. This pared down notion of what is said might be termed “what is literally said” in order to contrast it with the more or less enriched notion of Grice (and Levinson 2000).

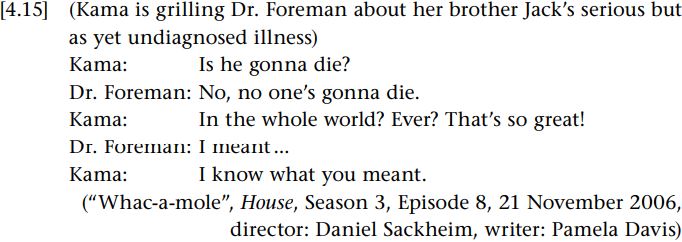

Work on courtroom interactions (Mosegaard-Hansen 2008), as well as observations about political doublespeak and lying (Horn 2009), suggest that speakers can indeed retreat to the literal meaning of their utterances if challenged. Consider the following example from the television series House (adapted from Horn 2009: 27):

Here Kama deliberately takes Dr. Foreman’s utterance No one’s gonna die literally in order to express irony, and perhaps also to express her worry and frustration about not knowing what is wrong with her brother.

Whether this retreat to a literal notion of what is said is regarded as legitimate or plausible in each case it occurs is a separate matter. What concerns us here is this shows us that such meaning representations are potentially available to users, and so it constitutes another layer of meaning representation that any theory must account for.

|

|

|

|

لخفض ضغط الدم.. دراسة تحدد "تمارين مهمة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

طال انتظارها.. ميزة جديدة من "واتساب" تعزز الخصوصية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مشاتل الكفيل تزيّن مجمّع أبي الفضل العبّاس (عليه السلام) بالورد استعدادًا لحفل التخرج المركزي

|

|

|