Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 25-5-2022

Date: 2023-07-08

Date: 17-5-2022

|

Referring expressions and common ground

Again, recollect our statement that “definite expressions are primarily used to invite the participant(s) to identify a particular referent from a specific context which is assumed to be shared by the interlocutors”. The idea of “assumed to be shared” is crucial in pragmatics. Note, for example, that the baby joke [2.21], is difficult to explain without reference to the notion of common ground (also broadly referred to as, for example, “mutual” or “shared” “knowledge”, “assumptions” or “beliefs”). Specifically in the joke, the idea of making assumptions about people’s assumptions arose (“we must assume that he thinks that the receptionist thinks that this refers to the voice on the phone and that the voice is that of her first baby”).

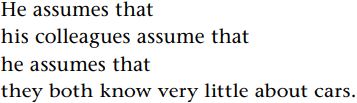

Herbert Clark and his colleagues (see Clark 1996; Clark and Marshall 1981) have made important contributions to the understanding of common ground. To illustrate the issues, consider that the first author is a closet petrolhead. Most of his colleagues in the world of academia would not know a connecting rod from a crankshaft. Consequently, if a conversation shifts to cars, he makes the assumption that they do not both have this background knowledge. Conversely, it is more than likely – given that his interests are hidden – that they make the assumption that he also lacks knowledge in this area. And conversations are tailored accordingly (e.g. cars are distinguished according to color and fuel consumption rather than whether their engines incorporate pushrods or overhead camshafts). Note what is happening here: assumptions are being made on both sides about what knowledge is common to both parties, that is, about common ground. Importantly, one makes assumptions about what assumptions are being made about what knowledge is in common: he assumes that his colleagues assume that they both know very little about cars. This is important because deciding what to say will, in part, depend on your assumptions about what you think the other(s) think you both know. One could make further assumptions about those assumptions about the knowledge you have in common:

And further levels could be added. Of course, this infinite recursion of assumptions is not the stuff of psychological reality – people would become mentally exhausted. Psycholinguistic research is not very precise about how many levels of assumptions are deployed in communication, some suggests we do not go beyond three, others suggesting at most six (see the research cited in Clark 1996: 100 and Lee 2001: 30). There is, in fact, another way of affording insights into this phenomenon, and that is by inspecting interactions themselves. People can check that assumptions about common ground are correct or repair understandings that appear to be based on erroneous assumptions about common ground.

Common ground can be seen as a subset of background knowledge, the subset that is relevant to communication because it is believed to be in common amongst the participants involved. Note here that we are more accurately talking about background assumptions and beliefs which are held with varying degrees of certainty rather than “knowledge”.4 On what basis might we suppose something to be common ground? One such basis concerns socio-cultural knowledge. We assume common information about: the practices and conventions of our cultures and communities (consider the shared information in academia); physical and natural laws; and experiences involving others. Another basis concerns personal experiences with other people. We assume common information about: whether others are co-present at an event or not; the kind of relations amongst us (friend/strangers, more powerful/less powerful); particular events; and particular discourses (see Clark 1996: 100–116, for an extensive elaboration of these bases). The fact that common ground involves, amongst other things, shared knowledge of particular discourses is important in a number of respects. Everything that is said in a discourse potentially constitutes part of the common ground for those participants party to the discourse, along with the other happenings that accompany that conversation (like the actions of participants, visual appearances, sounds). Discourse, of course, is dynamic, and, if it is, amongst other experiences, feeding common ground, then common ground is dynamic too – another issue to which we will return.

People tailor their referring expressions according to assumptions about common ground (cf. Clark and Wilkes-Gibbs 1986; Wilkes-Gibbs and Clark 1992). A definite noun phrase, a deictic expression or an anaphoric expression invites an interlocutor to interpret something in a particular way, often to pick out a particular referent in common ground. Whether or not your interlocutor will be able to do this is a calculated gamble based primarily on one’s understanding of the common ground that pertains. If you say can you repeat that please, you assume that your interlocutor will understand what your deictic that is referring to (e.g. the specific portion of discourse that you have both shared), or if you say can you pass me that, you assume that your interlocutor can understand that your deictic that is referring to the pepper mill she has just been using in front of you.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مجلةٌ عالميةٌ تنشر تفاصيل مشروع ملف تفويض المؤلِّفين العراقيين لحفظ التراث الفكري

|

|

|